A valuable, dangerous legacy

November 29, 2021

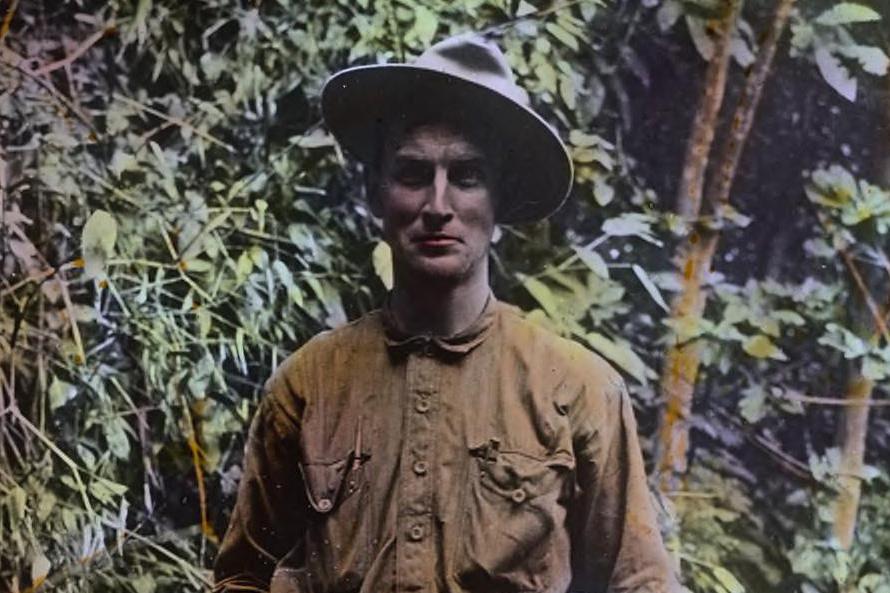

In 1904, Harry Alverson Franck set out for a year of travel. He had a brand new degree from the University of Michigan, $104 in his pocket, and a Kodak camera in his knapsack. That adventure resulted in his first book, "A Vagabond Journey Around the World," illustrated with more than one hundred photographs.

Over the next forty years, Franck published more than thirty illustrated travel books. In 1988, his children donated his archive, including thousands of photographs on nitrate film and glass, to the library.

Who was Harry Franck?

Franck’s first travel book opens with, “On the 18th day of June 1904, I boarded the ferry that plies between Detroit and the Canadian shore, and coasting the sloping beach of verdant Belle Isle, swung off on the first stage of my journey around the globe.”

The trip sprung from a casual conversation with friends, his fellow students at the University of Michigan. While they lamented that foreign travel was prohibitively expensive, Franck claimed that one could do it with no money at all.

A year after graduation — his degree was in modern languages — he set out to prove it.

Franck is careful to document that the $104 he had in hand was spent on photographic equipment and supplies; otherwise, he really did work and scrounge his way from start to finish. He picked up money doing casual labor and stayed in sailors’ homes and hostels for the indigent, and thereby saw the world from a very different perspective than other travel writers of this time.

Gripped by the wander bug, he spent the next 40 years traveling, writing, and lecturing — in addition to enlisting in two world wars, keeping a farm in Pennsylvania, and raising five children with his wife, Rachel Latta Franck.

Franck published 33 illustrated books to entertain the armchair traveler, at least one of which became a bestseller — "Zone Policeman 88," about the Panama Canal Zone. He wrote about Europe, South America, China, Japan, and many more places.

A rich resource

Franck’s photographic eye often wandered the open marketplace and streets. While most of his images include people, he also captured monuments, landscapes, outdoor work, and transportation. His perspective is not without biases and assumptions of Eurocentric superiority, but his writing suggests that he was a curious and largely tolerant wanderer.

His body of work offers a rich resource for research on topics he himself may never have imagined: the social history of ordinary people; the impact of turn-of-the-century colonialism; details of workaday clothing, tools, and trade; changes to shorelines or mountain passes over the past century; and perhaps others to come that we ourselves can’t imagine.

Combustible and toxic

There was just one problem. Or maybe two.

The cellulose nitrate film — also known as celluloid or nitrocellulose — that Franck used is notorious for being extremely flammable. It generates oxygen as it burns, which in turn feeds the fire, making it difficult to extinguish. After two decades of permitting us to mitigate the fire and health risks via careful storage, the university fire marshal politely but firmly insisted: we really could not continue to store this film in the Special Collections stacks.

And even setting aside the fire hazard(!), there’s another thing about nitrate film: over time, even when not ablaze, it’s constantly deteriorating, releasing noxious gases, and eventually reducing the film to a brown, sticky, gooey mess.

For both safety and preservation, we had been storing the film in securely wrapped packages in freezers, which slowed this deterioration. To get to the images, you had to thaw these packages, unpack them, and then re-pack them afterwards. This elaborate retrieval and storage method took a lot of time, not to mention the effort it would take for a researcher to try to read a flammable, noxious, off-gassing image in negative.

This frozen collection was both a safety risk and, for all practical purposes, hidden from view.

A 21st-century solution to a 20th-century problem

But we couldn’t discard it. We had more than 9,000 negatives, and the images they contained were unique and invaluable.

Fortunately, in 2019, we had a solution that wasn’t available in 1988, a solution that would satisfy both the fire marshal and the library imperative to preserve and share: digitization.

This complex, painstaking project was a joint effort between the Department of Preservation and Conservation and the Digital Conversion Unit (with additional support from the U-M Environment, Health, and Safety Department).

For a full account of the conversion process from the people who made it happen, view this Franck video presentation that offers details about nitrate film and its hazards, and the methodology, safeguards, and protocols that helped us succeed. It also answers the most frequently asked question about the project: yes, after digitization was complete, we were obliged to send the original nitrate film for HAZMAT disposal — a rare and unavoidable final step.

See the images and their descriptions at the Harry Alverson Franck Photographs collection. You can read many of Franck’s books online via the HathiTrust Digital library.

by Shannon Zachary and Lynne Raughley