Remembering Jan Longone

November 14, 2022

Jan Longone, who died in August at the age of 89, spent much of her life building an extensive collection of culinary publications. Today, the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive is recognized as a national treasure and a unique resource.

The collection, and Longone's tireless work to promote and share it, have already deeply influenced generations of students, researchers, and professional chefs, many of whom worked with her directly to navigate the archive that she knew so well.

“I first met Jan when I was researching the history of brunch," said Sarah Conrad Gothie, a writer and educator specializing in food and tourism studies. A new graduate with a master's in popular culture who'd never visited an archive or special collections before, she recalls feeling intimidated by all those scholars poring over historical texts.

"The moment I met Jan, that all changed. She was excited to hear about my project. She was interested in seeing what I might uncover. She made my project and me feel important.” Gothie remembers Longone as a charismatic storyteller, a discerning collector, and a tenacious advocate for the study of American culinary history.

“She was always busy — she had to be to accomplish what she did — and yet, she always found time to help others accomplish their goals too. She had a sharp intellect, a warm smile, and dauntless optimism,” Gothie said. “Jan loved books — loved reading them, collecting them, and finding homes for them."

Longone, Gothie said, had a talent for finding primary sources on American culinary history that were exceptionally rare, yet crucial to the writing of women’s histories, immigrant histories, and the histories of everyday people.

Collection highlights

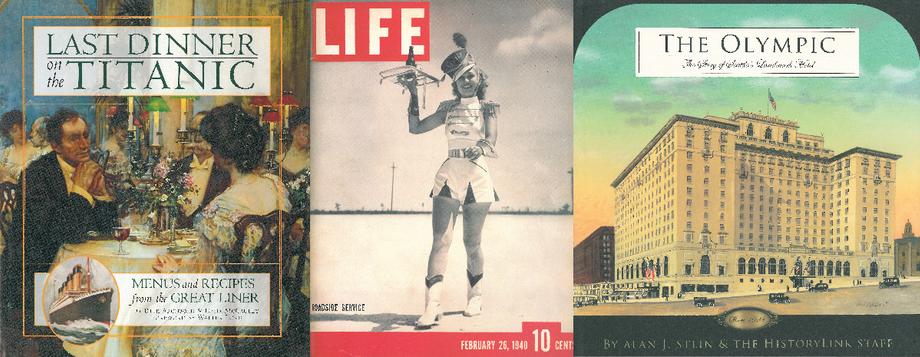

Among the 25,000 items are a large number of charity cookbooks — collections assembled by and for particular communities, often women's groups — in support of various causes. According to Juli McLoone, curator of the collection, Longone had a special passion and appreciation for them.

“Jan saw these unprepossessing collections of recipes — often spiral-bound, in black and white, and accompanied by local advertisements — not only as reflections of their communities, but as important sources of historical evidence of women’s empowerment and collective organizing skills,” McLoone said.

For Margot Finn, who teaches classes on food and food history at the University of Michigan, the charity and community cookbook collection stands out.

“A lot are from churches or other religious communities, and reflect the ethnic heritage of the community," she said. "These community cookbooks often feel like a bit of insight into the recipes that people really loved and made again and again, ones that are family favorites, things that people think of as their signature dishes and are expected to bring to every big party. You do get a sense of the community from the cookbooks they created together.”

Finn also points to The Swedish American Princess Cookbook for its insight into a particular moment in America, and as an example of how cookbooks offer instruction beyond the recipes they contain.

“Written in the 1930s, it really speaks to the tensions of the Great Depression — on the one hand, there's a desire to evoke luxury and wealth, to cook like royalty." But the recipes themselves, she says, are full of references to frugality, suggesting substitutions for, or ways to stretch, expensive ingredients like meat.

For McLoone, the most historically significant work in the collection — which spans the 16th through 21st centuries — is Malinda Russell’s A Domestic Cook Book: Containing a Careful Selection of Useful Receipts for the Kitchen. Published in Paw Paw, Michigan in 1866, Russell’s cookbook is the oldest known cookbook authored by an African American woman, and the library holds the only known copy.

A slim volume of 39 pages in paper wrappers, "A Domestic Cookbook" offers, before its recipes (or, the archaic "receipts"), a brief account of Russel's life — she was born a free Black woman in the South before Emancipation, worked as pastry cook, and eventually made her way to Michigan during the Civil War.

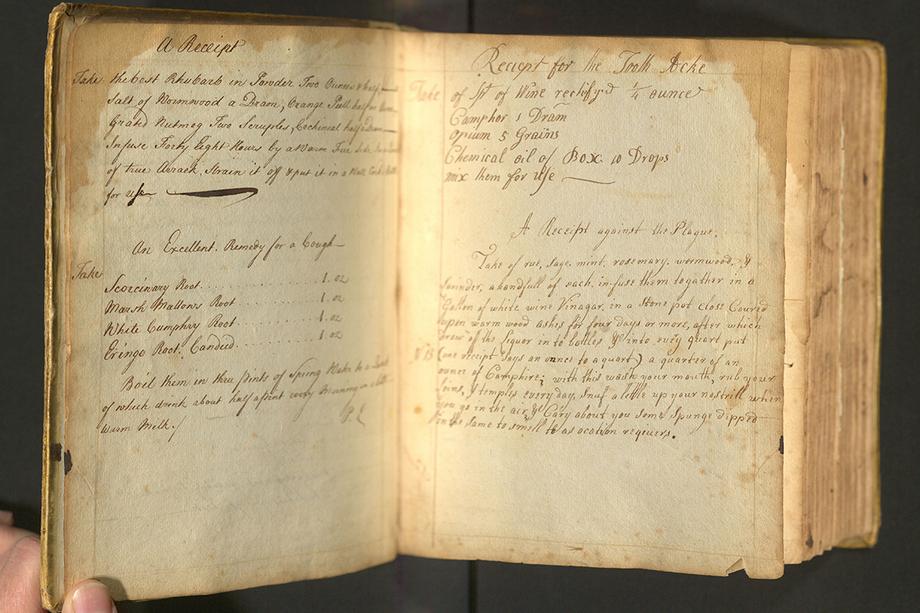

McLoone also cites one of the collection's oldest items, a 17th-century manuscript cookbook from England. “The paper and handwriting offer a delightfully visceral sense of the past, especially the way that the ink, probably containing iron, is eating through the page in places,” said McLoone. The book contains more than 130 recipes, including for fruit preserves, cheese, pickles, and even a “Receipt against the plague.”

It's impossible to know whether this, or any of the recipes, was ever tested — handwritten and printed materials do not often record who used them — but McLoone likes to remind people that cookbooks "are by no means the same thing as food diaries." Instead, they're a means to explore what people in a particular time and place wanted to eat. "Cookbooks reflect ambitions, desires, and dreams," she said.

Sometimes, though, you can tell whether a desire was fulfilled. "A cookbook with chocolate batter stains all over a cake recipe is a really lovely exception. Somebody really did use this artifact to make that cake 50 or 60 or 100 years ago,” McLoone said.

Where it all began

Dan Longone says his wife Jan Longone's interest in American cooking started at Cornell University in the 1950s, when he was a graduate student and she had recently left a graduate program in Chinese history.

After enjoying many shared meals, with students from abroad offering their home cuisines, the Longones got a request: Could they reciprocate with a typical American meal?"

“Jan said yes, but when we got home, she asked, ‘What is a typical American meal?’ So she went to the library, found some books, and began cooking." It was the beginning of a shared journey: building community around shared meals, pursuing that impossible-to-answer question, and finding a lifelong passion. Neither of them could have known it would last more than six decades.

That same year, he bought her a lifetime subscription to Gourmet magazine, whose entire print run from 1941 – 2009 (save one very rare issue) now belongs to the archive. This gift that kept giving cost him $48 — the subscription price minus his $2 coupon.

Longone, who is professor emeritus in Chemistry at the University of Michigan, described long drives to visit family in Boston, stopping their Volvo in small towns along the way to browse local bookstores for cookbooks.

“You could go into some of these places, in smaller towns especially, and you would see in the corner a basket of books on sale for a dollar each. And Jan would say, 'These are worth saving.' And they would be cookbooks put together by, say, the ladies of the Saint Episcopal Church as a fundraiser,” Longone said. Thus began the now fifty-state strong collection of charity cookbooks.

Jan Longone's reputation as a collector grew, and in 1972 she founded the Wine and Food Library, a mail-order bookshop run from their Ann Arbor home.

It was this reputation that brought Malinda Russell's book to her attention. Dan Longone remembers answering the call from a book dealer in California who was looking for information on a book she'd acquired, which had been published in Paw Paw, Michigan.

“Jan knew it was special just from the description, and she wasn’t going to let that go somewhere else,” Longone said. She didn't hesitate to pay the dealer's $200 asking price.

That was her way, he explained: Don't pass up a book you want; just buy it. And her determination to acquire the items she wanted was matched only by her determination to share them.

[an aside]

The culinary collection has informed countless students, home cooks, researchers, and professional chefs. Among them are Ann Arbor's Ari Weinzweig, founding partner of Zingerman's Community of Businesses, who credits Longone and her collection for helping him get his business started.

Chef Rick Bayless told The New York Times he might not have had his career without Longone and her collection, at the time housed in her home’s basement. “She would lead you down the rickety back stairs to her basement with all these dehumidifiers going and these metal racks full of books and you could spend as long as you wanted there,” he told The Times. “I thought I had struck gold.”

“The uses that we know about are always just the tip of the iceberg. Anyone can use the materials in our collection by request, and we don't document the research purposes of our visitors," McLoone said. And many of the public domain works in the archive are available in HathiTrust, so anyone with a connection to the internet can read them.

by Alan Piñon

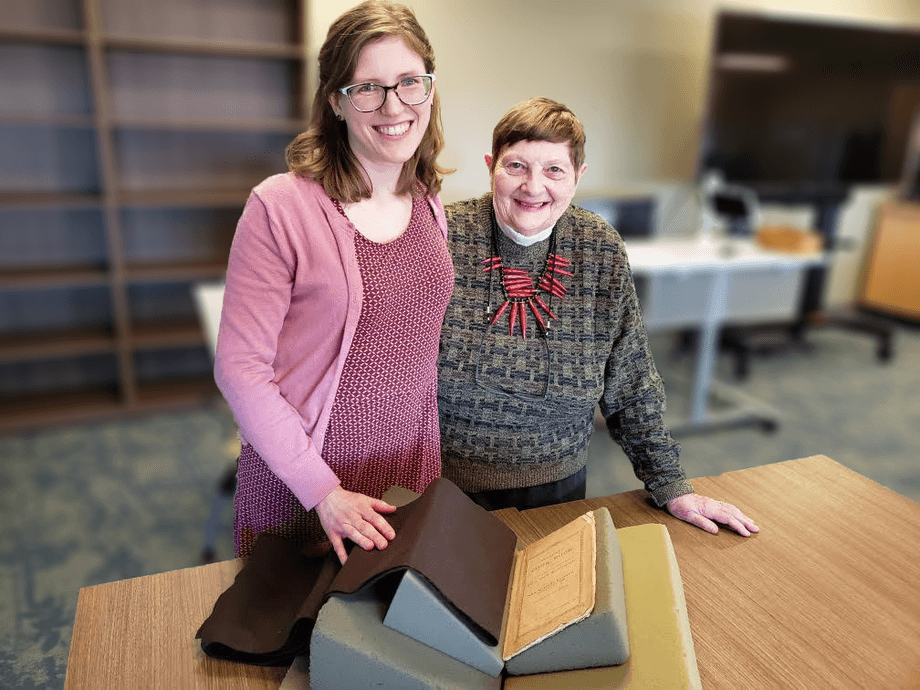

Juli McLoone and Jan Longone in the Special Collections Research Center. Photo by Jorge Avellan, WEMU.