Preserving the digital past

February 11, 2026

At the library's Digital Preservation Lab, a team of experts is proving that safeguarding our digital knowledge is as vital — and as human — as preserving print materials.

The lab itself is rather nondescript, with a few computers, stacks of floppy disks, a handful of external hard drives, and other relics of the not-so-distant past that once represented the cutting edge of digital storage and retrieval. To most people, they’re either unrecognizable or vaguely familiar artifacts from a distant past. But for Lance Stuchell, the lab's director, these superannuated items are the keepers of important knowledge that must be preserved and made accessible to current and future scholars and researchers.

“A lot of people assume that things are safe just because they’re digital,” Stuchell says. “But digital doesn’t mean permanent. It just means that they're fragile in a different way than books and paper.”

For the past several years, Stuchell has led a small but steadily growing team that specializes in the care and preservation of digital materials — everything from decades-old documents written in word processing programs that no longer exist to born-digital archival materials and web-based collections. Under his leadership, the unit has evolved from mostly a consulting service to a hands-on preservation lab.

And while the work may not require traditional library conservation skills — largely focused on paper and bookbindings — it is every bit as meticulous, and every bit as vital to preserving knowledge, especially when so much of it is created and shared by means of bits and bytes.

From advising to hands-on preservation

When Stuchell joined the unit, the work mostly centered around informing the campus community about best practices. “We’ve always been advising people about formats and storage,” he says. “But over the past few years, our portfolio has grown so much that we had to become more hands-on.” This growth comes from more and more materials that include digital media or pre-digital fragile formats (videotape, cassettes) whose contents need to be transferred to digital media or be eventually lost forever.

The shift is visible in the lab itself, a blend of modern computing and retro technology that looks part modern computer lab, part Radioshack. Here, staff back up old media, extract data from deteriorating disks, and log every artifact’s journey from its origins to safe storage. Each step in the process is carefully documented to preserve its provenance — the record of how and when something was migrated or modified — so every item's authenticity can be verified.

“Everything’s so easy to alter in the digital world,” Stuchell says. “Our role is to make sure that the files we preserve are exactly what they claim to be. That trust is what libraries are built on.”

It’s work that requires both technological fluency and creativity. Stuchell’s team doesn’t just rescue items, they preserve meaning, context, and credibility. When a future researcher opens a digital manuscript, listens to an oral history, or examines an archived website, they'll be relying on a chain of trust that reaches back to this lab and to a complex, dispersed network of institutions around the globe.

Digital doesn’t mean preserved

For many people, the phrase digital preservation seems redundant. Isn’t the advantage of digital that it lasts forever?

“Like paper, bits also decay over time,” Stuchell says. “Magnetic media degrades. A one can turn into a zero as a result of this decay. And formats become obsolete faster than you’d think."

It’s a truth anyone who’s ever tried to open a decade-old file knows too well. “You might have a Word document from 2007 that won’t open on today’s software,” Stuchell says. “Now imagine a library promising to keep materials accessible not for ten years, but for a hundred.”

That promise requires vigilance. The unit runs regular integrity checks, verifying that files haven’t changed or become corrupted. They store multiple backups in different locations, guard against hardware failure, and document every intervention.

“It’s about transparency. If we alter something, we record that change, and explain exactly what we did and why.”

Digital preservation, in other words, is not about freezing archival digital materials, but ensuring they remain readable and trustworthy as technology evolves.

A big challenge, Stuchell says, is that they are preserving for a future we can’t predict.

Fragility and resilience

If there’s one theme running through every aspect of the lab's work, it’s fragility. Every file needing preservation is relying on software that may vanish, hardware that may fail, and tools that may hinge on the work of a single programmer, working alone in another country.

“Most of the software we use is open source,” Stuchell says. “Sometimes it’s literally one person in Europe maintaining it. If that person takes a vacation, or retires, we’re stuck.”

The global community that supports digital preservation is passionate, but it’s also thinly spread. “It’s fragile,” Stuchell says. “So we build in redundancies. We try to have a plan B for everything.”

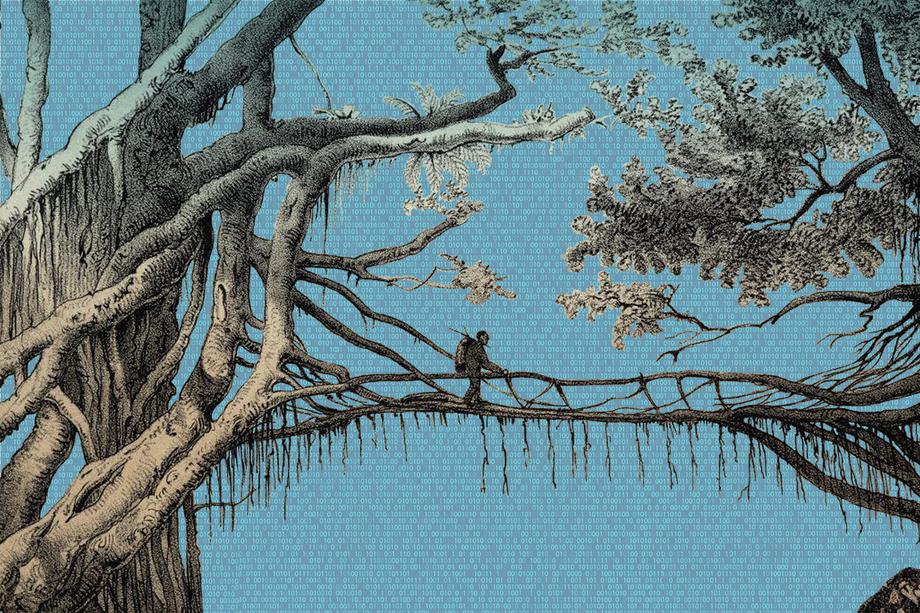

That mindset — nimble, adaptive, and transparent — is what he believes will define the next era of digital librarianship. “We’re building the bridges as we cross them,” he says. “And we’re mapping the way as we go, so others can follow.

A bridge to the future

That unpredictability makes digital preservation a field of constant reinvention. Today’s tools might not exist tomorrow. Yesterday’s hardware may already be impossible to find. The team’s solution is equal parts ingenuity, resourcefulness, and experimentation.

“We use everything from the newest software tools to old floppy disk readers,” Stuchell says. “They don’t make five-and-a-quarter-inch drives anymore, so we hunt for them online and test which ones still work.”

It’s an unusual mix of high-tech and kludgy problem-solving. “We’ve borrowed a lot of ideas from the video game community,” he says. “People who want to play vintage games have figured out ways to connect old media to new computers. We’ve adapted that for our preservation work.”

Their lab may not be stocked with hundreds of antique machines, but each piece of hardware that survives becomes a lifeline to recovering data that would otherwise be lost. “It’s like having a Rosetta Stone for technology,” Stuchell says. “If we can read it, we can save it.”

Mentoring and growth

One of the most exciting changes in recent years has been the addition of new staff. Among them is Abby Sypniewski, a recent graduate whose journey as a Lafer intern* to full-time team member illustrates the growing importance of digital preservation as well as the all-around value of student internships.

“When I started as an intern, I had no idea this field even existed,” Sypniewski says. “I thought my background in coding would prepare me, but so much of this work is improvisation and experimentation. We’re constantly troubleshooting.”

Sypniewski’s curiosity quickly found a home in the lab. She describes her early days as a crash course in digital archaeology, working with everything from floppy disks to hard drives. “I quickly learned what provenance meant here,” she says.

Stuchell, for his part, sees Sypniewski’s growth as a sign of how far the field has come. “When I started, there weren’t internships for this kind of work,” he says. “Now, we’re training the next generation of preservationists.”

Sypniewski’s presence has also expanded the lab’s reach. With her on board, the unit has been able to take on new projects, from analyzing file formats to helping preserve special collections materials.

Technology, trust, and the library’s mission

In an age when artificial intelligence can fabricate images and falsify text, the ability to establish authenticity has never been more urgent. Stuchell’s team treats that challenge as both a responsibility and a calling.

“There’s already so much distrust online,” he says. “Libraries have always been trusted institutions. Our role is to make sure that trust extends to digital content.”

That’s one reason the team approaches emerging technologies like artificial intelligence with caution. “We’re watching it,” Stuchell says. “But we’re skeptical. We need to be able to guarantee authenticity, and right now AI just isn’t built for that.”

Instead, the lab focuses on sustainable, human-driven processes that balance innovation with accountability. “We should justify every tool we use,” Stuchell says. “If AI can make materials more accessible, maybe. But we have to weigh the cost — environmental, ethical, and human.”

Expanding what it means to collect

Digital preservation isn’t just about saving what’s already inside the library; it’s also about reimagining how libraries collect in a digital age. Through web archiving, the team helps preserve the online presence of communities and organizations that might otherwise disappear from history.

“The web is where culture lives now,” Stuchell says. “Our web archiving projects often capture the voices of underrepresented groups. For some of them, their websites are their primary record. That’s part of what makes this work so powerful.”

The team also empowers researchers to take preservation into their own hands. Sypniewski helped create a research guide that teaches scholars how to archive their own materials, from government websites to social media posts.

“People want to make sure their sources don’t vanish,” she says. “We’re helping them do that.”

“Libraries have always been about access and stewardship,” Stuchell adds. “We’re just extending that mission into the digital world.”

He sees a future where digital preservation is as fundamental to librarianship as cataloging or conservation. “We’re at the beginning of that curve,” he says. “In a hundred years, people will look back at what we’re doing now the way we look at early paper conservation. It’s experimental, sometimes improvised, but essential.”

Despite the computer- and technology-driven nature of the work, there are distinctly human characteristics that make it possible: patience, curiosity, and a core belief in the value of knowledge.

“Our job,” Stuchell says, “is to make sure people in the future can still learn from the past. Whether it’s a medieval manuscript or a floppy disk, it’s all part of the same mission.”