Past practices seed a sustainable future

December 11, 2025

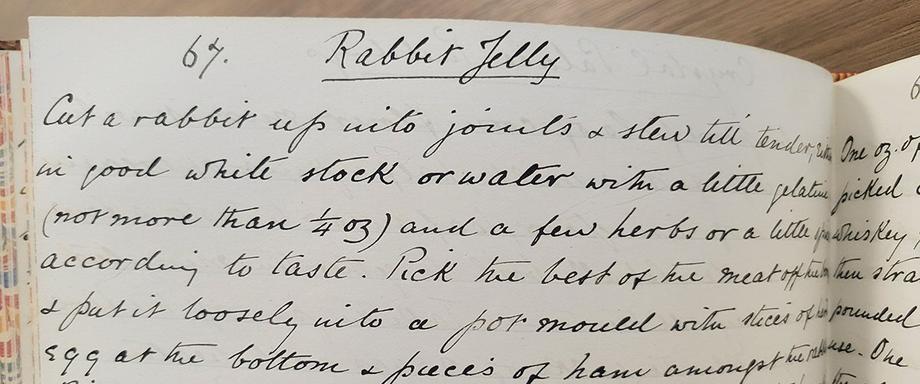

While flipping through a recipe book from the late 1800s, Kennedy Kavanagh, a freshman majoring in biology, came across a handwritten recipe for rabbit jelly, which reads:

Cut a rabbit up into joints and stew till tender, either in good white stock or water with a little gelatine (not more than 1/4 oz) and a few herbs or a little spice according to taste. Pick the best of the meat off the bones & put it loosely into a pot mould with slices of hard egg at the bottom & pieces of ham amongst the rabbit. Bits of parsley look nice. Strain the gravy into muslin & pour it into the mould which must not be filled too full of meat — Annie [Jarvis], 1888

Kavanagh, who used the irresistible but anachronistic (and trademarked) term Jell-O to describe the dish, admitted that it probably wouldn’t appeal to the modern American palate. But it is a prime example of what she and her classmates were looking for in their examinations of a selection of historical cookbooks and recipes.

The recipe’s methods — the use of the whole animal, bones and all, and the encasement of the meat in gelatine to delay spoilage, a technique whose heritage dates back centuries — demonstrate ways of preparing food that are becoming vital to movements seeking a sustainable future.

That rabbit jelly, a cold meat dish known as an aspic, sits alongside hundreds of other recipes, medicinal remedies, and food preservation practices that students and researchers can find in campus libraries. Kavanagh and her fellow students in "ENVIRON 245: Cult or Culture: History of Sustainability and Zero Waste Movements" visited the Special Collections Research Center to study a selection of historical family recipe books from the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive and the William L. Clements Library.

What is old is newly sustainable

Learning from the past in order to innovate new sustainable practices is a core aspect of Cult or Culture, a class taught by Nikki Roulo, an instructor in LSA’s Program in the Environment.

The class challenges students to identify and problem solve issues in current sustainability movements, and to recognize how historical cultures can influence and inform current environmental practices. The archives offer tangible objects that record a different worldview toward the lifecycle of objects, and a record of past sustainable practices and ideas.

Roulo said visiting the archive is critical to the class’s learning objectives, and also to the final project, in which students develop an exhibit that offers a solution to a current sustainability issue that’s informed by historical practices. Past students have presented food samples and recipe transcripts to develop strategies for eliminating food waste; an exhibit of paper made from class notes using 17th century practices; ink and house cleaners made from historical recipes; and examples of clothing mended and amended to fit the changing styles throughout the lifetime of an aristocratic woman.

These projects addressed problems like food waste and rot, overpackaging, overconsumption, and household chemicals in watersheds.

History comes to life

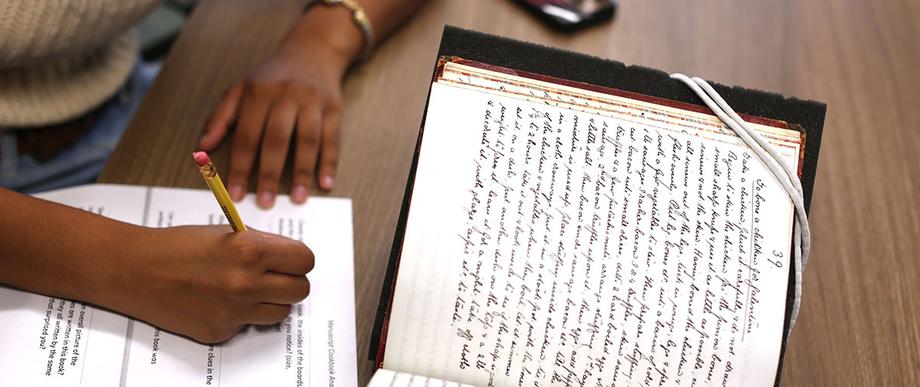

Getting to see and hold unique materials sparks interest and insights that are harder to come by via digitized artifacts and other online research.

“My students’ excitement when encountering these archives is infectious,” Roulo said. “There is a realness to handling the archives. When students are able to touch, read, and in some cases, smell what they have been theorizing about, they suddenly become more connected to the material, and to past writers and collectors. The worldviews, concerns, and issues become tangible.”

Students have observed, among other things, how these recipe books sometimes reveal economic shifts in a family, or provide evidence for a period’s environmental or agricultural shifts.

Freshman Eloise Nelson said that feeling the paper and reading the handwriting and finding notes tucked into the pages was “a really cool experience” compared to looking at digital facsimiles on a computer screen. “It makes the history feel a lot more alive.”

“Looking at the old recipe books showed me how everyday life has always been connected to sustainability. People reused ingredients and relied on seasonal availability in ways that reflect sustainable habits, even if they weren’t labeled that way at the time,” she added.

Juli McLoone, curator at the U-M Library, who led the class session alongside Maggie Vanderford, librarian for instruction and engagement at the Clements Library, said students always observe the marked difference between digital and physical access to rare materials. Even the best digitized versions — like the high-resolution images from the Folger Shakespeare Library Digital Collections the class used in an earlier session — have limitations.

For example, the "Pumpelly Family Recipe Book" from 1812 is a pocket-sized volume with every page densely covered in scrawling writing with a pocket at the back, now empty, but presumably meant to hold notes or clippings. In contrast, the "Waldo-Sibthorp Family Recipe Book" is a substantial volume bound in red, with leather corners and spine, and a gold stamped title. “But online,” she said, “everything is the size of the screen you’re looking at.”

And no screen could convey the feel and texture of the paper and cover, or the construction of the back pocket in the Pumpelly book (which expands out like a file folder), or the series of blank pages in the Waldo-Sibthorp book (blank pages aren’t typically scanned, for obvious reasons), which are followed by a run of upside down and backward recipes (because a subsequent owner had turned the book around and started from the back).

And while some of these qualities and features — measurements, for example — are specified in the metadata, a researcher has to understand why such details are interesting in order to even notice them. By becoming proficient handlers and observers of physical manuscript cookbooks, students become more observant and insightful users of digital facsimiles.

Although neither the Pumpelly nor the Waldo-Sibthorp books have been digitized, McLoone said that hundreds — if not thousands — of historical cookbooks of all kinds are available online, including many from the Longone archive.

But in some cases, the best thing about having access to online facsimiles is that they can lead people back to the originals.

by Alan Piñon

~~~

The manuscript cookbooks the students examined are collections of recipes compiled by individuals, sometimes over more than one generation. Some of these volumes have detailed provenance information (specific dates, locations, information about the situations of the families that kept them). Others have a provenance so scant that “19th c. America” is all that is known for certain.

The recipes are handwritten or scrapbooked (that is, pasted-in magazine or newspaper clippings), blurring the line between published and not, and often identify recipes as having been shared by friends or family members.

Because the handwritten material — mostly cursive, with many variations in style — can be challenging for students to decipher, McLoone and Vanderford provided some training on how to read historical handwriting before their session with the cookbooks.

Curator Juli McLoone and students examining the Waldo-Sibthorp Family Recipe Book.