It’s not just about the birds

December 21, 2023

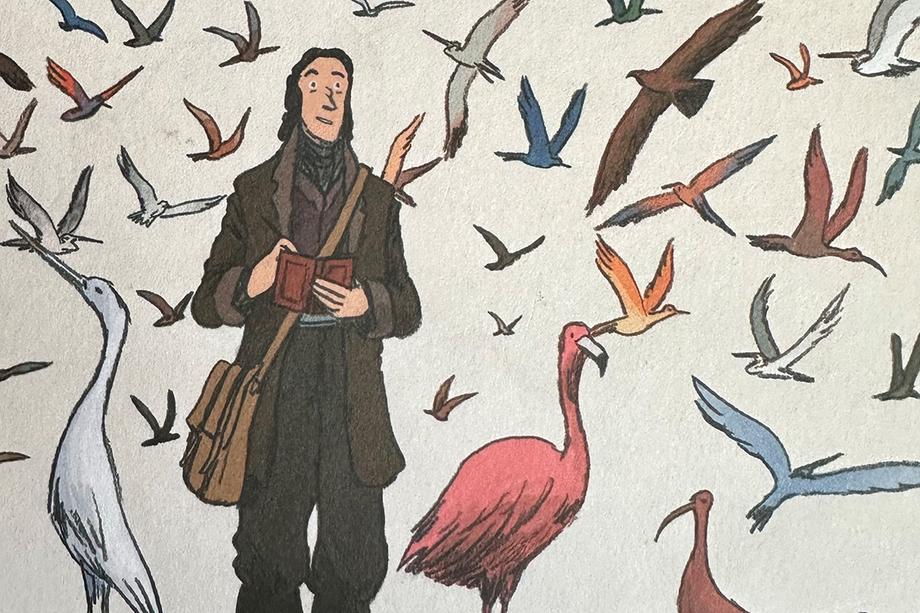

John James Audubon, the artist and naturalist who traveled the country in the early 19th century, killed a lot of birds to create his best known work, The Birds of America — famous for its 435 life-sized, hand-colored prints depicting various species of birds in their natural habitats, and famously the first book purchased by the U-M Regents in 1838.

Audubon wasn’t alone; it was the practice of the time to capture, kill, and taxidermize animals in order to study and draw them. Audubon most certainly drew on his field observations of live birds, but he is known for an innovative technique of posing dead specimens in lifelike postures, which vivified the images and set his work apart.

What’s more, according to "Audubon: On the Wings of the World," a beautifully illustrated graphic novel published in 2016, sometimes, after killing and eviscerating birds, he also reassembled, resurrected, and then released them, somehow unharmed after all. This last bit reflects the purposeful mixing of truth and fiction that Audubon propagated in his journals — the source material and inspiration for the book.

And this particular flight of fancy does little harm; it’s not credible on its face, and was perhaps intended to airbrush the stark realities of the work he did. But Audubon, a known enslaver and vocal anti-abolitionist, stretched, softened, and obscured much more important truths, and his falsehoods became source material for serious historical texts.

The myth became the man

“As often is the case in recounting the accomplishments of historical figures, Audubon is largely presented as a singular individual who overcame remarkable obstacles through the sheer force of his own talent, ingenuity, and genius,” said Jason Young, U-M associate professor of History.

“But, peeling the layers back, we find a different and, to my mind, a much more interesting story that includes a broader group of people who played crucial roles along the way. Some of those people were women, enslaved Africans, and Native Americans; people whose historical contributions to the development of the country have long been given short shrift.

Mythmaking reveals important truths

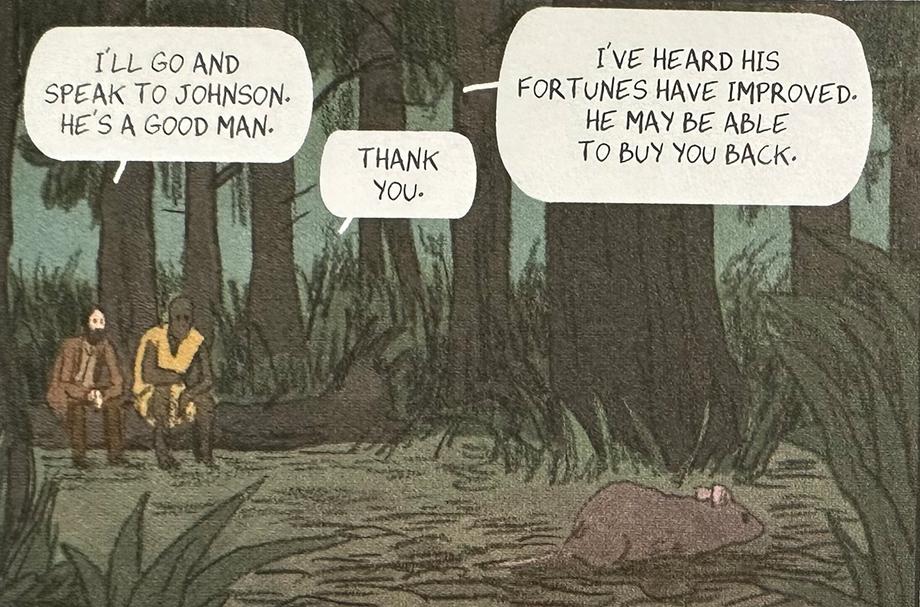

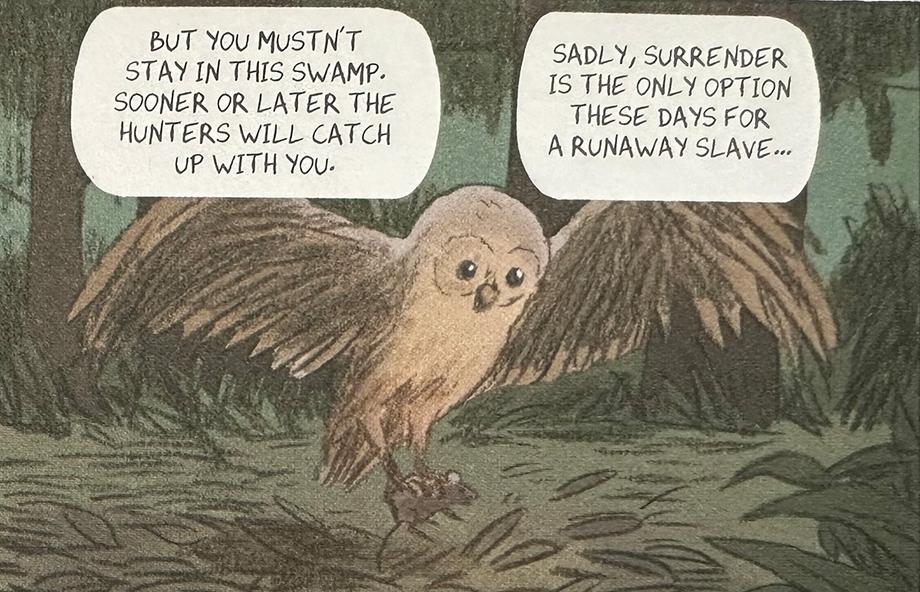

One of the stories Audubon told about himself, and that the authors of "On the Wings of the World" chose to highlight, portrays Audubon as a savior of an escaped enslaved Black man and his family in a Louisiana swamp. This “salvation” turns out to be a return to the enslaver who’d sold and separated the family in the first place — a “decent man,” the account insists, whose financial hardships had forced him to separate the family.

This story, true or not, portrays Audubon as an enthusiastic supporter of property rights over human beings, and yet is favorably recounted in a 21st-century work.

In other words, the authors of "On the Wings of the World," who dismiss Audubon’s acknowledged faults as mere “foibles” in their foreword, are more interested in perpetuating the myth than in scrutinizing the man.

Young offers a different way forward — one that doesn’t require sacrificing an important historical work of art and ornithology.

“The most compelling treatments of his life and work will take the whole of him into account,” he said. “We can appreciate the important contributions Audubon made to our understanding of the natural world while still looking squarely at his full life, without flinching from or excusing the less desirable parts of his biography.”

The reckoning

Those associated with Audubon have, in recent years, been taking Young’s approach, trying to bring into focus a more accurate picture.

At the University of Michigan Library, this examination resulted in some changes: in 2023, the library announced that the primary exhibit space in the Hatcher Library, which has "The Birds of America" on permanent display, would no longer bear his name.

Young described the library’s action as part of a nationwide effort to reconcile Audubon’s undeniable flaws as a human and his undeniable accomplishments as an artist and naturalist. “This reconsideration of Audubon is also part of a larger reckoning with the various legacies of racism in the United States,” he added.

"The Birds of America" remains on display in the Hatcher Gallery Exhibit Room, with new labels that address Audubon’s complicated legacy and also acknowledge the uncredited contributors, many of them Indigenous people and enslaved Black people, who worked alongside Audubon to realize the ambitious project.

According to Curator Juli McLoone, who was part of the project to revise the labels, “It’s not about replacing a glorified image of Audubon with a vilified one, but rather with a more accurate one that acknowledges his achievements as well as the harms he participated in.”

The reconsideration, ultimately, is about revealing the truth. “By studying his life and work, we also learn about the sometimes uncomfortable history of scientific knowledge production,” McLoone said. “And we get to shine a light on the contributors whose work Audubon failed to acknowledge.”

by Alan Piñon

Detail of John James Audubon depicted on the cover of "Audubon: On the Wings of the World."