Arts & resistance in the library

December 7, 2023

The fall 2023 U-M theme semester, Arts & Resistance, sought to “reflect on how creativity and making can arise out of oppression and destruction” because “even when people are stripped of their agency and humanity, they turn to creativity as a way to reclaim some of this agency and resist dehumanization.” (Quotations are from the theme semester website.)

Throughout the semester, the library shared collection materials and perspectives via exhibits, panel discussions, open house events featuring on-theme materials and topics, and a book giveaway during Banned Books week (Let Freedom Read).

And in less public settings, students taking theme-related courses visited the library for a very close look at some materials that illuminate some of the forms and histories of arts being used as resistance.

The posters

Is all art at some level political? Do politics need art? How do artists organize for social justice? Is there an art to political engagement? And what about our own artistic production or political action? These are just a few of the questions students in Artful Politics (Writing 160: Multimodal Writing) were tasked with considering.

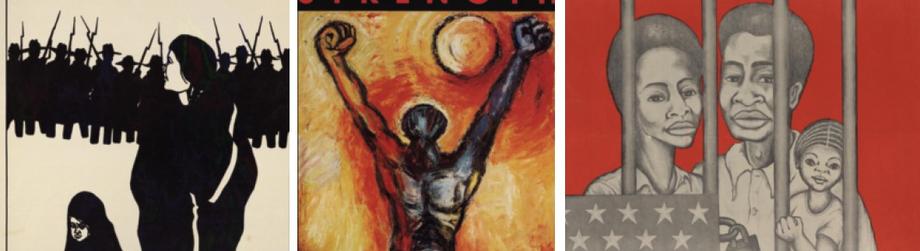

And early in the semester, they came to the Special Collections Research Center in Hatcher to examine and discuss just some of the hundreds of protest posters that belong to the Labadie Collection.

“Visiting the Labadie Collection was a really nice opportunity to get them into a place they haven’t seen before, and to have them take on the role of researcher and historian to study these artifacts. They were super into it,” said the course’s instructor, Teaching Professor Naomi Silver.

The topics the posters addressed encompassed racial segregation during the 1960s and the disproportionate arrests of Black people, gentrification in New York City boroughs and the resulting rising rent prices, nuclear proliferation during the Cold War, legalization of marijuana, prison abolition, the Graduate Employees’ Organization negotiations in the 1990s, and more.

The students’ examination of the posters was purposeful: the related writing assignment would ask them to analyze a work they considered to be political — one of the Labadie posters, or something else of their choosing — and analyze 2-3 specific elements that contribute to what they understand to be its most important message.

The Labadie posters were just one of the modes the students were set to take in. Among the others: a University Musical Society performance, a Museum of Art Curriculum Collection, contemporary music, political speeches, and social justice manifestos, all aimed, Silver said, at teasing out the complex interactions of politics and art.

In the end, the students get to choose the materials, modes, and political topics they write about, but they’ll have to identify and consider the artful dimensions of that topic.

“And they will vary widely,” Silver said, “which is part of the fun.”

The music

Who writes protest songs and why? What does music do for the oppressed? How does a protest song become folk music? What is my music? And what does that say (or not say) about my identity?

These are questions considered by students in Protest Music of the United States (Musicology 345) throughout a semester that included trips to the Museum of Art, the Clements Library, and the U-M Library — where each was handed a printed piece of protest music from the Labadie Collection.

The items ranged in format, size, and age, from single-sheet broadsides to pamphlets to booklets, spanning protest movements over two centuries. The students’ examinations were guided by a set of questions about their physical characteristics, audience, authorship, research value, and the issues they addressed and/or left out.

Assistant Professor Henry Stoll encouraged the students to think like musicologists, though most of them aren’t studying music. As they examined, photographed, and discussed the items they’d received (the distribution was random), they were preparing for a writing assignment. Stoll wants their analysis of the pieces to identify the intended audience, the point of view, the purpose, and to assess whether and how the piece might have once given rise to civil disobedience or political resistance.

Stoll, who’s fairly new to the university — this is his second year at the School of Music, Theater, & Dance — found in the theme semester an opportunity to take up a topic that’s perhaps underserved in the academy.

“Some protest music is thought of as musically mundane, and not ‘artful,’ because it’s typically created by changing the lyrics to well-known music.” This technique — the term of art is contrafactum — goes back a long way, and has obvious benefits for singing in groups, from Gregorian chants to national anthems (“The Star Spangled Banner” is one example) to protest marches.

He’s also frankly excited to share with students some “fantastic music” by artists that might not be familiar to them, like Philip Ochs, k.d. lang, Jimi Hendrix, and others whose cultural significance lies at the intersection of musicality and protest.

Students getting a close look at musical artifacts from the Labadie Collection. Photo by Lynne Raughley.