I recently came across this sixteenth-century introductory manual designed to teach Christian biblical scholars how to read and understand works in Hebrew and other Oriental languages without punctuation and stress marks. But what makes our copy remarkable is that the names of well-known Protestant scholars, and other infidels, have been carefully crossed out, that is, expurgated, following the Holy Inquisition's recommendations to censor authors considered heretical according to the teachings of the Church of Rome.

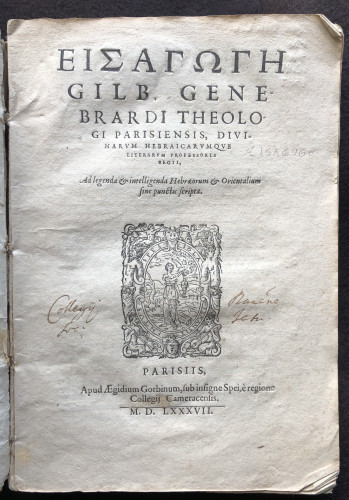

Gilbert Genebrand. ΕΙΣΑΓΟΓΗ Gilb. Genebrardi theologi parisiensis, divinarum hebraicarumque literarum professoris regii. Ad legenda & intelligenda Hebraeorum & Orientalium sine punctis scripta (Paris: Gilles Gorbin, 1587)

The inscription on the title page reveals that the book belonged to the library of a Jesuit Collegium in the Polish town of Rawa, located in central Poland: Collegi(um) Ravense, Soc(ietatis) Jesu. Understandably, the students at this Catholic institution would have expected the expurgation of those "personae non gratae."

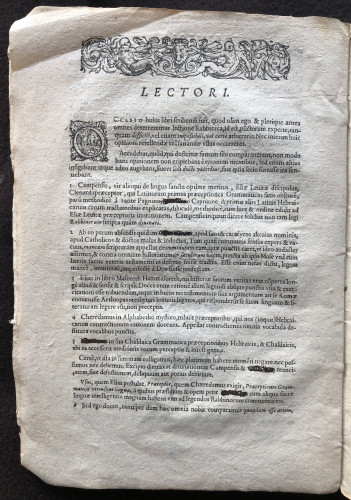

Letter to the Reader from Gilbert Genebrand. ΕΙΣΑΓΟΓΗ Gilb. Genebrardi theologi parisiensis, divinarum hebraicarumque literarum professoris regii. Ad legenda & intelligenda Hebraeorum & Orientalium sine punctis scripta (Paris: Gilles Gorbin, 1587)

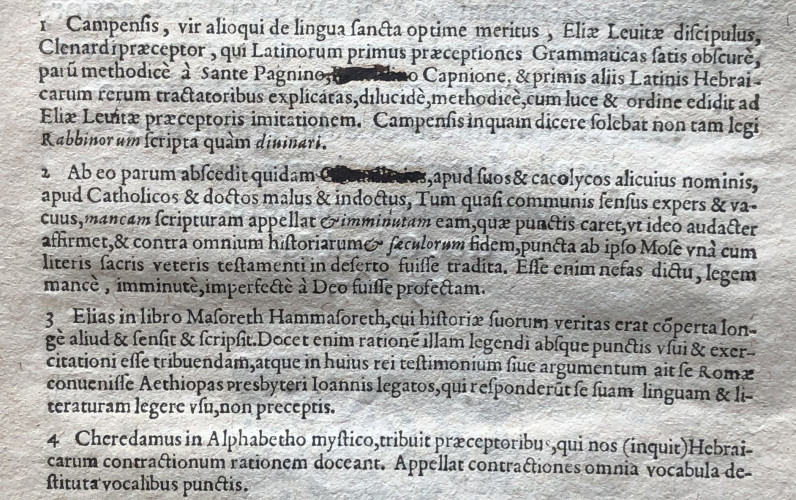

But who are those people? A quick examination of a non-expurgated copy allows us to unveil the crossed-out names on the page displayed above: they are Reuchlinus, Chevallerius, and Munsterus, in fact, the Latin versions of Johann Reuchlin, Antoine Rodolphe Chevallier, and Sebastian Münster, all of them famous Hebraists who ran into trouble with the Church for various reasons, some because of their allegiance to the Protestant cause, others because of theological discrepancies. Moreover, these names had been inserted in numerous editions of the infamous Index Librorum Prohibitorum (List of Forbidden Books), which listed authors and publications condemned by the Catholic Church as heretical. Essentially, the Church saw the Index as a very useful weapon to minimize the impact of Protestant authors, overall attempting to exercise control over the printing press. The first Index, which included 230 titles, was issued by the University of Paris in 1544. Subsequently, updated versions of the Index were published across Europe for the next three centuries.

Detail of the Letter to the Reader from Gilbert Genebrand. ΕΙΣΑΓΟΓΗ Gilb. Genebrardi theologi parisiensis, divinarum hebraicarumque literarum professoris regii. Ad legenda & intelligenda Hebraeorum & Orientalium sine punctis scripta (Paris: Gilles Gorbin, 1587)

It is unmistakable that the Church's antagonism towards these Hebraists was connected with the publication of the first fully commented Rabbinic Bible in Venice in 1517. Published by Daniel Bomberg and edited by Felix Praetensis, this Bible became a standard reference text, particularly for protestant Hebraists throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It included not only the Hebrew text of the Bible painstakingly edited from several manuscripts, but also the Aramaic Targums (translations and interpretations of the Bible mostly dating from before the sixth century), and Jewish commentaries composed between the twelfth and the sixteenth centuries. For many authorities and theologians of the Church the main challenge was that, while these Jewish commentaries certainly offered considerable linguistic help and powerful insights into the interpretation of difficult passages, they also mirrored the authors' conviction that Judaism was the only true religion. Specially, David Kimhi's commentaries of the Psalms strongly challenged the interpretation of Christian readers. Hence, to prevent future problems with the Church, Bomberg purged Kimhi's most controversial statements, collecting them in a separate leaf that could be included or left out according to the buyer's wish. Clearly, Sebastian Münster (one of the expurgated names in our copy) was one of those buyers who accepted that controversial leaf. Indeed, Münster used the text of the 1517 Rabbinic Bible for his own edition of the Hebrew Bible published in 1535, providing also his own Latin translation as well as explanations and summaries of the Jewish commentaries. Since Münster's main approach to the biblical text was linguistic and pedagogical, his candid engagement with the controversial opinions of the Jewish commentators angered many of his contemporaries, including some Protestants like Luther himself. Therefore, it is in this context, I believe, in which we need to examine the expurgation in this manual, which, ironically, and potentially, would have facilitated the reading of those forbidden commentaries.

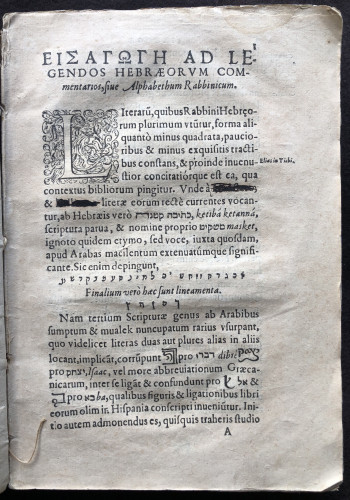

First page of Gilbert Genebrand. ΕΙΣΑΓΟΓΗ Gilb. Genebrardi theologi parisiensis, divinarum hebraicarumque literarum professoris regii. Ad legenda & intelligenda Hebraeorum & Orientalium sine punctis scripta (Paris: Gilles Gorbin,1587)