The body human

October 6, 2023

On a Friday in September, on the main floor of the Taubman Health Sciences Library, a group of undergraduates watch in awe as Kai Donovan peels away layer after layer from a cadaver with just a gentle sweep of her finger across a screen. First, she removes skin to reveal musculature and tissue, which then gives way to the vascular system, and then, finally, nothing but bones are left. But with a quick swipe in the opposite direction, all is back in place. The digital cadaver is once again whole.

Donovan, a Learning Technologies Specialist, is conducting a quick tutorial on how to use the library’s Anatomage Table, a 3D digital display for examining, dissecting, and manipulating a virtual cadaver with astonishing precision, and without the need for scrubs, a lab, or an actual human body.

According to Donovan, the table is aimed primarily at students of medicine and in the health sciences, but on that day the students gathered around it were in The Art of Anatomy (Movescie 313), an interdisciplinary mini course made possible by a grant from the U-M Arts Initiative. Their focus was as much on the Anatomage Table itself — the medium used to depict the human body — as on the information conveyed by the images they were seeing and manipulating.

“The overall idea behind the course is to introduce students from various majors and disciplines to a compelling category of objects — anatomical models of the human body — and encourage them to develop critical thinking skills by evaluating how depictions of the human body have changed to reflect the expectations of their intended audiences,” said Jennifer Gear, lecturer in the History of Art, who teaches the class along with Melissa Gross, who holds faculty appointments in both the School of Kinesiology and the Stamps School of Art & Design.

The students each took a turn using the table — rotating the brain this way and that, slicing long cross sections of the body, pulling it apart — while the others observed closely, taking copious notes.

A study in contrasts

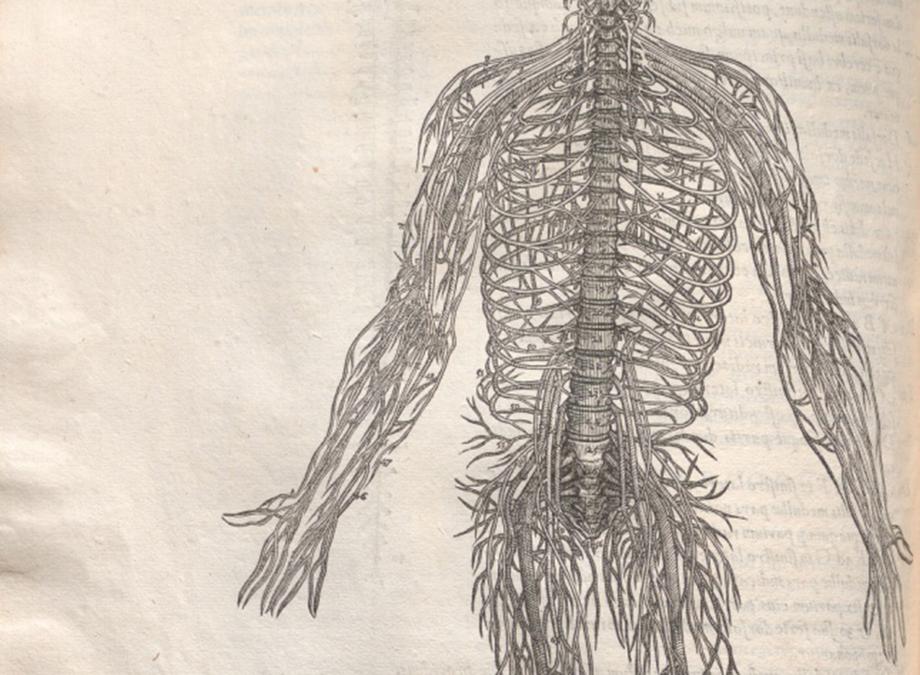

At the forefront of their minds were other representations of the human body, which stood in stark contrast to these luminous digital versions. The week before, at the Special Collections Research Center in the Hatcher Library, they had examined a collection of old and rare anatomy books from the 16th–19th centuries.

Although many of the books in the collection are viewable online, Gear made the visit to Hatcher so that students could engage with these primary sources in real life, as the audience they were printed for would have done.

Among these works was De humani corporis fabrica libri septem (On the fabric of the human body in seven books) by Andreas Vesalius, a famous text published in 1555 that they'd been primed to see by an earlier class reading assignment.

“The images in these books were surprising to many students. They show animated bodies, walking through classical landscapes, holding open their partially dissected bodies, and showing interest in the revelation of their own anatomy,” she said.

For Caroline Dean, a biomedical engineering major, the anatomy books were her first experience interacting with physical materials from the library's special collections.

“Many of these drawings are unlike any other anatomic models I have ever used before," Dean said. "I'm so used to working with very modern and scientific representations of the body, and it was refreshing to see a more artistic approach.”

Putting their observations to the test

In the next phase of the class, students brought to bear their experiences, which had also included handling animal bones, to sketch their own anatomical drawings and sculpt clay models. They'll also discuss their observations and consider the ethics of using human remains in university teaching collections. Each will keep a weekly journal to analyze and expand upon their experience of the in-class activities.

“They aren't making artwork, per se. Rather, the arts-based activities are more about a haptic approach to learning — gaining knowledge about human bones by using their hands to feel the structures of the bones, and then articulating that through drawing and modeling," Gear said. "We contrast that with the intangibility of digital scans of the human body, including high-res photos, the Anatomage Table, and various VR environments.”

Owen Faulkner, a third-year Aerospace Engineering major, is enthusiastic about the approach and the range of materials.

“I was immediately intrigued by the uniqueness of the content, blending both art history and kinesiology. Being in the College of Engineering, it isn’t very often that I take courses about contextual artistic thought, let alone courses whose purpose is to blend various disciplines,” he said.

“One of the gifts of this class is its breadth. The ability to actually experience nearly 500 years' difference in anatomical modeling in a single week, moving from the Vesalius prints to the Anatomage Table, is something not many courses can provide.”

by Alan Piñon

Students surround the Anatomage table in the Taubman Health Sciences Library.