Native Americans

In the past few centuries, Native American tribes have faced great difficulties fighting for their rights, lands, and autonomy. The federal government of the United States has often disregarded Native Americans, focusing instead on the needs of its white citizens. This disregard goes back to the early days of colonization and expansion, and arguably continues to this day. Colonizers in the 18th and 19th centuries abused the trust of many Native American tribes, forcing them off their land and taking their resources. A multitude of wars and battles were fought between white settlers and various Native tribes from the 16th century to the end of the 19th century. The United States government often coerced tribes into signing unfair treaties with terrible terms simply to survive in the face of systematic violence.

Native American tribes have also faced significant challenges to their cultural and religious practices. Even those white settlers who were somewhat sympathetic to the plight of Native Americans generally believed the only acceptable future was full assimilation into Anglo-American society as sedentary agriculturalists and Christians.

Viewers should note that the majority of the publications in this section of the exhibit come from a white perspective, in part because white Americans generally had greater access to printing and the written word. Tracking the lives and movements of Native Americans through the eyes of their oppressors is an imperfect strategy, but such documents can reveal how harmful misconceptions in early encounters continue to affect Native populations.

Soumaya Hachemi, Estrella Salgado, Austin Teholiz and Molly Wilson

Opposite the title page is a frontispiece showing a landscape. Captioned "Seat of King Phillip," the name of a quartz rock formation, it shows a Native American sitting on the ground in front of a river, fishing. The landscape is largely untouched, but a boat is visible in the distance.

Lydia Maria Child was a teacher, writer and activist that lived from 1802-1880. She was concerned with women’s rights, Native American rights, abolition and American expansion to the west. Child was interested in giving a more accurate history of Native American society than was commonly accepted by many of Euro-Americans at that time. This fictional children’s book details the cruelties committed by New Englanders on Native Americans through the perspective of a mother telling her daughters about the wars of the 17th century. Child was also concerned with the way religious bigotry played a role in the conquest of Native Americans. Child was interested in presenting the Natives differently than they had been in literature written Previously by Euro-Americans. She was an opponent of westward expansion because she believed Native Americans would perish if they were forced to move. Most of her books circulated widely in the United States but The First Settlers was her most radical book. There were no reviews written about it, suggesting she or her publisher may have wanted to keep its publication quiet to protect her reputation. Most Euro-Americans of the time denied, obscured, or justified the violence perpetrated against Native Americans, making Child’s book a stark contrast with other accounts of her time.

Laurynn Green and Jane Wentrack

This treaty is commonly known as the Second Treaty of Chicago. The page displayed has a seal with an eagle clutching arrows and an olive branch along with the words "Andrew Jackson President of the United States" above the first page of the treaty text. The First Treaty of Chicago, was signed between the Michigan Territorial governor and the Council of the Three Fires. The Native American tribes agreed to leave most of Michigan, with narrowly defined exceptions, and some parts of Indiana and Illinois. The Second Treaty, also known as the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, followed a similar pattern to its predecessor. In this treaty, the Potawatomi tribe agreed to cede various lands around the Great Lakes, including large parts of Wisconsin, Illinois, and what little they still held in Michigan. In exchange, the Potawatomi tribe was promised cash payments as well as land west of the Mississippi. The treaty was signed on September 26th, 1833, and in 1835 the Potawatomi left their lands for the west.

Both treaties are representative of the large number of agreements between the United States and various Native Tribes where representatives of the United States government sought to move Natives out of lands desired by Euro-American settlers moving west. These treaties varied between agreements made by sovereign states with reasonable sincerity on both sides to (in many, many instances), documents that essentially forced Native Americans from their lands with the most illusory of token agreements.

Joshua Corsello and Jim Milleville

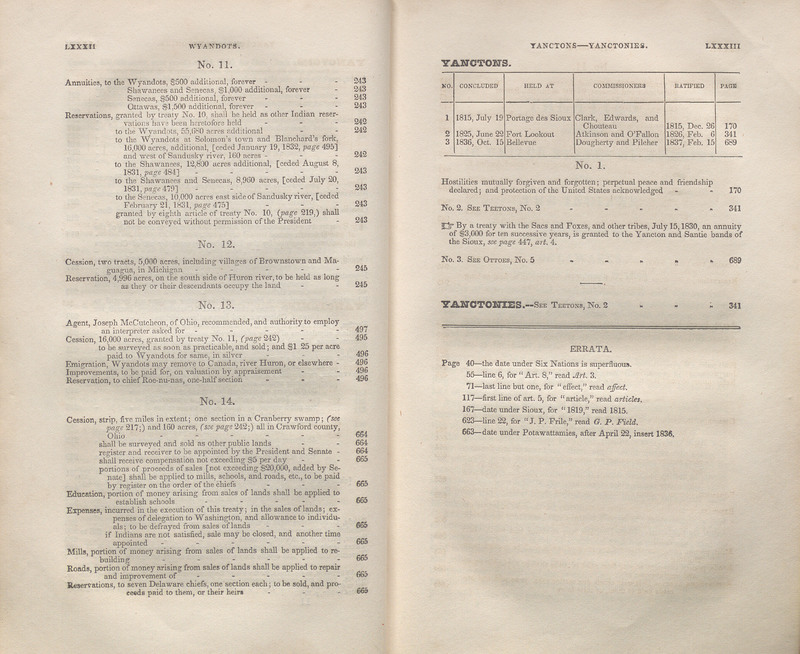

On display are the final pages in the table of contents of this collection of treaties between the United States government and various Native American tribes. Listed are several examples of treaties. Most deal with land cessions, emigration, and reservations, though some deal with education or other improvements. There is also a space for error corrections, where the editor notes various faults in the treaties.

Treaties Between the United States of America and the Several Indian Tribes was published in 1837 in Washington D.C., under the supervision of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Carey A. Harris. Harris was a supporter of the Indian Removal Act under President Jackson, which is part of the reason why he was appointed. This Act forced many Native American groups to cede their land to the federal government and move west under threat of violence. Treaty compilations were often created for government or law offices, so clerks and officials would have an immediate reference material when discussing specific topics. This book contains treaties dating between 1778 to 1837. Most of the earlier treaties had less harsh—if often paternalistic—provisions than later ones. In one early treaty, “Deaf, dumb, blind, and distressed” Native Americans would be provided for by a fund set up by the government, and whiskey was confiscated to “promote industry and sobriety.” The treaties peaked in hostility around 1830, coinciding with the Indian Removal Act and its focus on land cessions to the exclusion of all else.

Austin Teholiz and Molly Wilson

This thin paper pamphlet, browned with age and without illustrations, dates back to 1843, a time in America when many citizens of European descent knew little about Native American lives and culture. John D. Lang depicts the lives of certain Native tribes in an informative, journalistic piece intended to educate an audience of his fellow Quakers. John D. Lang and Samuel Taylor Jr. were appointed by a meeting of the Society of Friends in Philadelphia in 1842 to travel to Indian communities and identify ways that Quakers might be able to assist them. The passage on display shows the beginning of Lang’s description of the Kansas Tribe. While sympathetic in some ways, Lang’s perspective and choice of vocabulary are representative of a widespread belief among Euro-Americans that Native culture was barbaric and required reform and assimilation for the Natives’ own benefit.

Madison Gagne and Kelsi Hackney

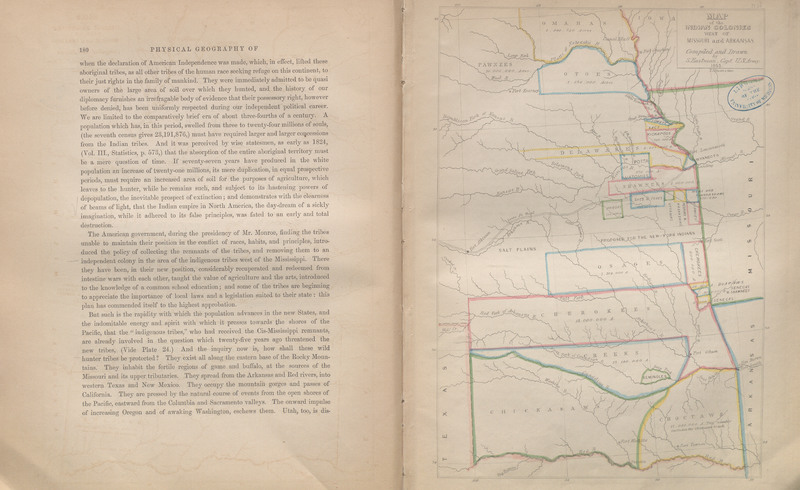

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft was a prominent 19th century Indian agent and ethnologist, part of a nascent academic field devoted to analyzing and comparing cultures. Schoolcraft learned the Ojibwe language, from his wife, Jane Johnson, who was of Anishinaabe descent, and he documented Native American culture. He was commissioned by Congress to produce an exhaustive overview of histories and cultures of the numerous Native American tribes that bordered the United States at the time. The page on display concerns the tribes of the Mississippi River basin during the period when the expansion of the United States forcefully displaced millions of Native Americans from their ancestral homeland. Tribes like the Delawares originally inhabited the east coast, the Cherokees lived in Appalachia, and the Potawatomis lived in modern-day Michigan, yet as the map shows, they were all pushed west of Mississippi.

Inevitably, such concentration of different tribes caused tensions and intermittent conflicts between tribes struggling to survive in new territory. In this passage, Schoolcraft attempts to justify such violent expulsion as "civilizing" the Native Americans, yet even he later acknowledges that they already produced elaborate works of art and oral tradition independently of European influence. Schoolcraft’s survey exemplifies the contradictory efforts by the United States to assimilate the Native Americans while also pushing them off their land. The map on the right shows the reservations in what is today eastern Oklahoma. The borders of each tribe as well as the state borders are highlighted with colored lines. Most tribe names are shown alongside their population for each territory, from 15 million Choctaws to 67 thousand Senecas.

Sara Richards and Maxim Sharipov

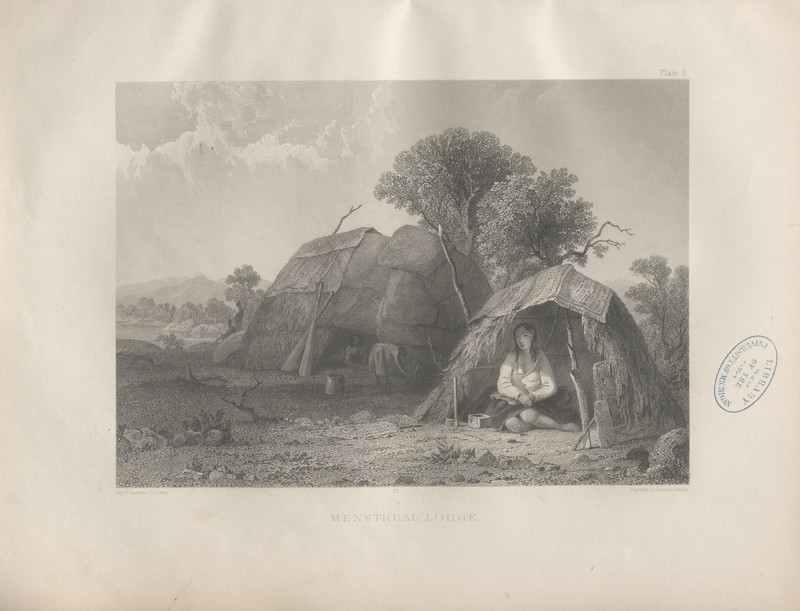

On the far right of this full-page, black-and-white lithograph, a young Native American woman sits alone in a small menstrual lodge. She has a somber expression on her face, and her hands are folded on her lap. In the distance, there are two male figures looking away, heightening the woman’s isolation.

Schoolcraft’s six volume series about Native Americans, created for government officials, highlighted aspects of Native American culture that white Americans would have found scandalous. Menstruation is tied to female sexuality, and that was not a respectable topic in 19th century America. Schoolcraft described he "lunar retreat" pictured above as the most significant Native custom, and he asserted that anything a menstruating woman touched was considered "ceremonially unclean." This description perpetuated the Christian narrative of impure, untrustworthy women, first seen in the Biblical story of Eve. However, the illustration is inaccurate, because it only depicts one woman. There likely would have been other menstruating women in the lodge, and they would have been been sharing stories and performing their own rituals.

A more nuanced approach to female sexuality is visible in Schoolcraft’s account of the connection Native Americans made between fertility of women and land. The mother of the household would walk around the fields at night to protect to the crops from pests. Unfortunately, his derisive tone, shown in phrases like "The Indian mind appears to be so constituted," hinders Schoolcraft’s credibility to modern readers. However, his research is still valuable, for it shows how American scholars began early studies of Native Americans.

Soumaya Hachemi and Estrella Salgado

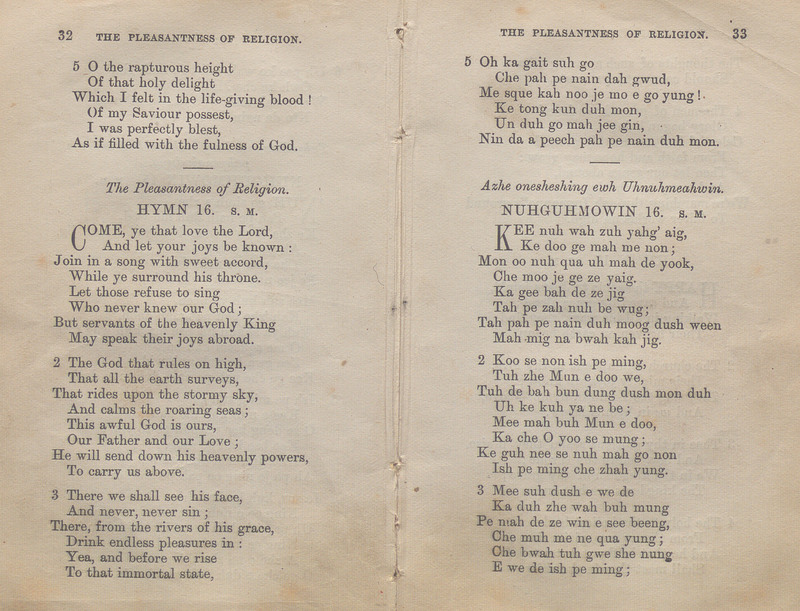

This collection of hymns from 1860 is a small volume with a simple red leather cover. It was a well-used book, now falling apart at the seams and the pages are ripped and stained. The book has hymns in both English and Ojibway languages, shown next to each other on each page.

Peter Jones used his bilingual skills to put this book together as a tool for his fellow Ojibwe people to assimilate into European culture. The son of a Welsh surveyor and Ojibwe woman, he spent his life preaching Christianity and bridging the gap between colonial culture and Ojibwe culture. Jones’ life is a direct reflection of the growing number of marriages occurring between European and Indigenous groups at this time.

The Ojibwe people lived in the Great Lakes region and experienced tremendous pressure to convert from the arriving colonists. Each of the hymns focuses on Christian practice and values. All reference God and emphasize a strong commitment to faith. These hymns were written? for the Ojibwe, with the goal of learning to recite them. The collection provides insight into the relationship between the Natives and the European settlers. The Ojibwe lost much of their culture due to colonialism, and Jones encouraged Ojibwe people to assimilate by learning English and converting to Christianity. This piece also reflects the emergence of a new group of people: a mixed race, which would stir the pot for future conflicts.

Sophia Little and Macy Perovich

Description and Travel

Religion