War of Words. War of Images.

Debating religious themes during the early Reformation sparked the need for ever more deliberation. Reform ideas—expressed in many media and languages—mobilized men and women, clerics and laypeople, rulers and commoners, the literate and the non-literate. Ultimately, this participatory moment gave way to the gradual formation of distinct religious communities. Various means and measures instilled a sense of belonging among believers for their own confession as well as a disdain for their rivals. Still, despite verbal venom and actual violence, an uneasy coexistence emerged over time.

This view shows the city of Wittenberg bookended by the castle at its western end and the Augustinian monastery (where Luther lived) at its eastern, with the market and its church in the middle. Wittenberg gained significance when Frederick the Wise, Elector of Saxony, took residence in the town on the river Elbe and founded a fledgling university in 1502 where Luther started teaching in 1508. In 1517, Wittenberg had approximately 2,000 inhabitants and relatively few students. Compared to the largest cities in the empire such as Cologne or Nuremberg with ca. 40,000, it was a minor settlement – and the fact that there existed no monastic foundation in town other than the Augustinians confirms this assessment. That one of the greatest challenges to Catholicism originated from such a seemingly undistinguished place was a bitter pill for traditionalists. In subsequent decades, the town’s reputation as well as the university’s excellence attracted residents, students, and scholars from all over Europe.

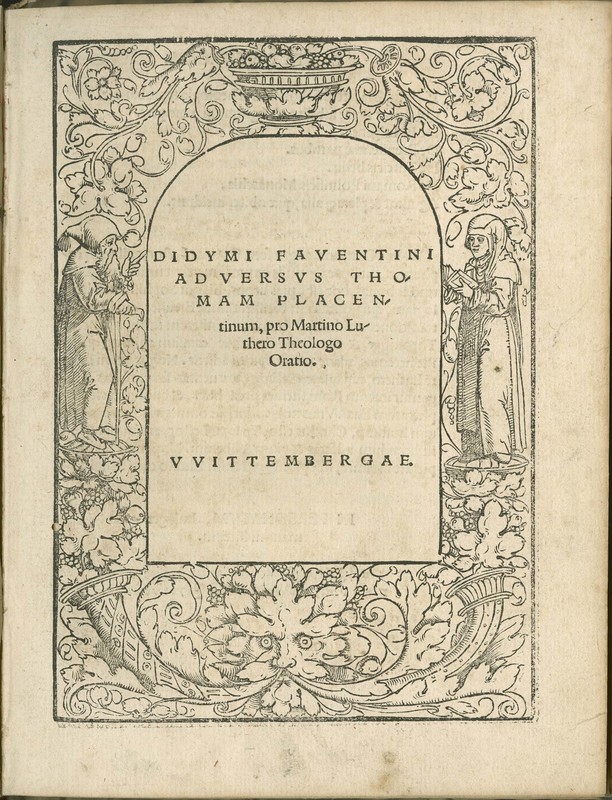

15. Melanchthon, Pro Martino Luthero oratio (Oration in favor of Martin Luther), Wittenberg, [1521]

The Leipzig Disputation of 1519 was intended to bring the theological controversies that had gained prominence since 1517 to a resolution. Observers saw the Catholic theologian Johannes Eck, one of Martin Luther’s most brilliant opponents, as victorious over Wittenberg professors Andreas Karlstadt and Luther. Yet in the war of words that ensued (of which our text is part), those who favored religious reforms succeeded.

Though he had not participated in the event, Philip Melanchthon, a professor of Greek at Wittenberg since 1519 and one of the greatest intellects of his day, stridently attacked opponents by name while using a pseudonym for himself except for a subscript in Greek letters. With unusual polemical venom, he expresses core Reform concerns through a humanist critique of scholastic theology.

Notably, the pamphlet’s title page, designed by an unknown artist, represents a religious hermit or monk (to the left) and a religious woman or nun as if engaging an audience. In fact, women actively participated in debates on both sides of religious reforms.

16. Luther, An den christlichen Adel deutscher Nation (To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation), Basel, 1520

To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation is the first of three signature treatises Martin Luther authored in the decisive year 1520. Written in German, the estimated print run for the first edition alone amounted to 4,000 copies. This fact speaks volumes about printers who sought to make a profit publishing Luther’s work. Indeed, the German public’s thirst for the reformer’s writings was almost insatiable in the early 1520s with the first edition selling out within two weeks.

This call for renewal of the church concludes with a list of “twenty-seven proposals for improving the state of Christendom.” The treatise is essentially a blueprint for the future course of the Reform movement: since Luther declared the Catholic Church hierarchy as incapable of improvement, Christian rulers needed to take initiative and initiate religious renewal.

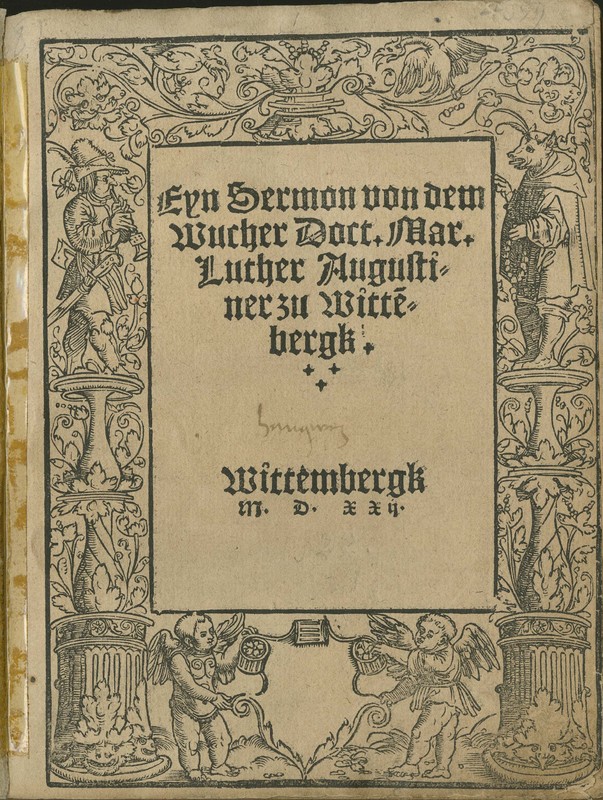

17. Luther, Eyn Sermon von dem Wucher (A Sermon [Treatise] on Usury), Wittenberg, 1522

Great wealth poured into the German lands during the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Technological advances allowed for extensive mining—the industry in which Luther’s father earned a comfortable income. The accelerated pace of economic change and the increasing demand for capital tore at the extant social order. Luther’s treatise on usury commands our curiosity because it provides a haunting glimpse of these transformations. However, those expecting him to deliver a theory of capitalism will not find it here, as Luther advocated moral responses and Christian compassion to address social and economic inequity.

Our edition of Luther’s treatise inaugurates a fascinating volume containing Protestant publications on economic matters, starting with Luther and reaching into the early seventeenth century.

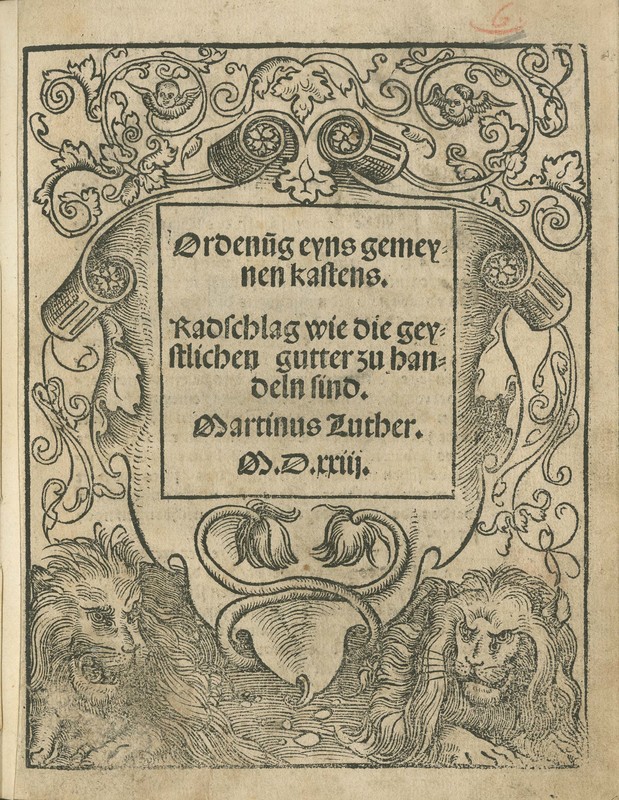

18. Luther, Ordenung eynes gemeynen Kastens (Ordinance for a Common Chest), [Wittenberg], 1523

The religious reforms of the sixteenth century fundamentally transformed the communities where they were implemented. When ecclesiastical institutions such as monasteries closed, fell into disrepair, or were disbanded, their holdings had to be re-organized, their finances re-ordered, and the buildings re-purposed. The town of Leisnig in Saxony approached Luther for advice on these issues, specifically how to handle former church assets. In his response, Luther devised a plan that could also be applied in other communities: A common chest of income was to be administered by elected officials to fund communal projects, poor relief, charities, and education for the benefit of the whole parish. This order was an important step in the formation of Protestant communities, as they benefited from or came to terms with these transformations.

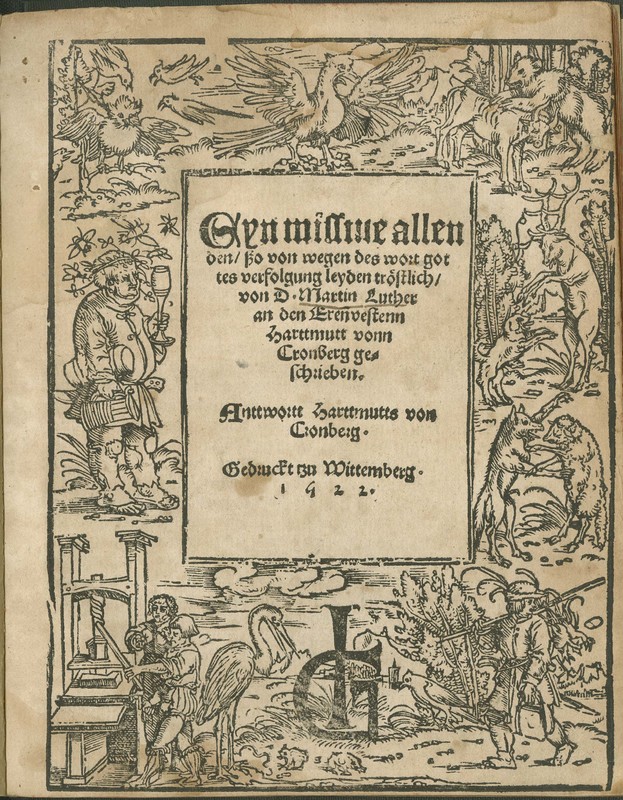

19. Eyn missiue allen den / ßo von wegen des wort gottes verfolgung leyden tröstlich (An Open Letter of consolation to all who suffer persecution because of the Word of God), Wittenberg, 1522

This publication—an exchange of letters between Martin Luther and Hartmut von Cronberg, a noble, early follower, and pamphleteer—models mutual support in times of adversity, when evangelical truth, as von Cronberg and Luther saw it, was under duress in the empire.

The woodcut border framing the title, a remarkable work of art by an unknown artist, is worthy of our attention. Johannes Rhau-Grunenberg, who ran a print shop in Wittenberg’s Augustinian monastery between 1508 and 1523, used this same title frame for nine other Luther prints. In addition to several more humorous scenes, the woodcut shows two workers operating a printing press in the bottom left corner, next to a stork—an animal with positive associations—and the printer’s monogram. The first known visual representation of a printing press dates to 1499/1500, approximately 50 years after its invention. Since images of printmaking are exceedingly rare until the mid-sixteenth century, our title page represents one of the earliest examples.

See also: map of Wittenberg

20. Conrad Distelmair. Ain trewe ermanung, das ain yeder Christ selbs zu seiner seel hail sehe…[Augsburg: Heinrich Steiner] 1523

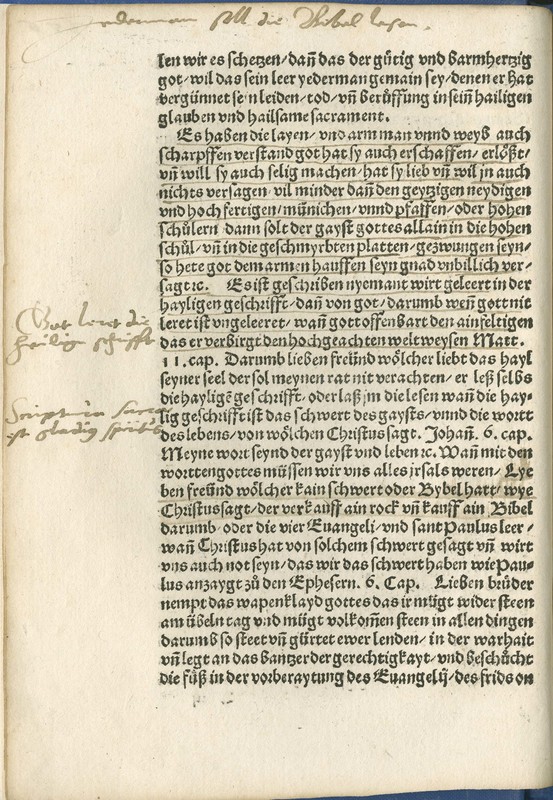

During the early 1520s, laypeople actively participated in religious debates, and some of them, like Konrad Distelmair, even had their “admonitions,” as the somewhat daring title has it, printed. Little is known about Distelmair other than that, in addition to our pamphlet,

he also published a dialogue of laypeople, a genre popular at the time.

Here, Distelmair calls on everyone to read the Bible for themselves. Since individual salvation depends on one’s own familiarity with the Christian message, no one should rely on clerical mediators.

To substantiate this point, biblical quotations abound in his discussion. He even takes up the question of what the non-literate or those who could not afford prints should do, recommending that they ask others to read aloud or beg for money to purchase religious books for self-study. The sixteenth-century reader who marked up our copy with underlining and marginalia seems to have agreed. As he or she summarizes the gist of the author’s argument on the upper left corner of the page shown: “Everyone should read the Bible” (Jedermann soll die Bibel lesen).

See also: 22

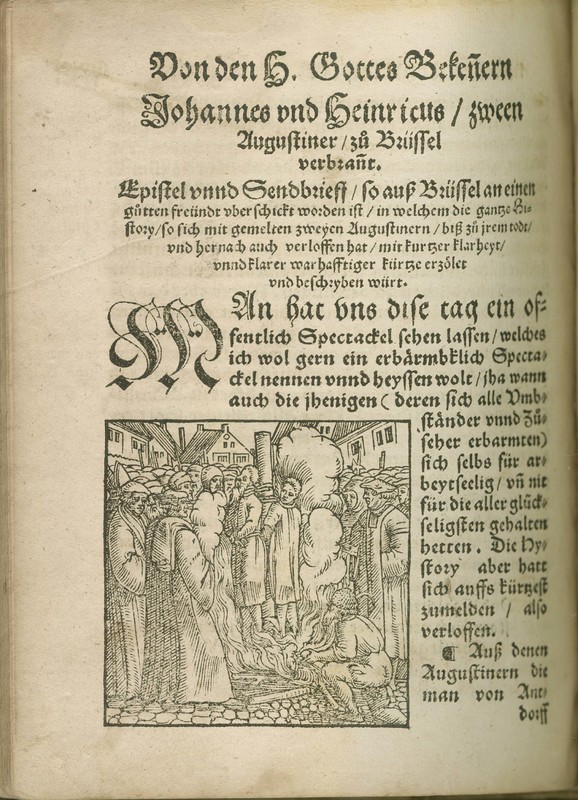

21. Ludwig Rabus. Historien. Der Heyligen Außerwölten Gottes Zeügen, Bekennern vnd Martyrern. 8 volumes. Strassburg: Samuel Emmel, 1556-7.

Generations of Reformers after Luther painstakingly recorded and recounted the events that we now know as the Reformation. With recourse to the past, they shaped Protestant memory for the future. Stories about the sacrifices individuals made for their beliefs provided readers with examples to emulate, instilled an admiration for their religious forebears, and, importantly, confirmed the conviction that they constituted a distinct group. Ludwig Rabus’s multi-volume publication is a pioneering endeavor in this regard, one of the first comprehensive histories of the Lutheran Reformation, which is evidence of the Histories of God’s Chosen Witnesses, Confessors, and Martyrs, as the title has it.

The page on display narrates the events that led to the first executions of ‘evangelicals’ for their beliefs—two Augustinian monks (like Luther) from Antwerp. A third with whom Luther corresponded died in prison. Rabus not only provides an account of what transpired, but he also includes documents quoted in full with the narrative.

22. Albrecht Dürer. Underweysung der Messung, mit dem Zirckel und richtscheyt, in Linien Ebnen und gantzen Corporen. Nuremberg: Hieronymus Formschneyder, 1538

The Peasants’ War of 1524-1525 was one of the largest uprisings in European history. The rebels expressed grievances against rulers’ encroaching prerogatives, and they also demanded a community’s right to choose their own priest. These and other demands inspired various social groups to mobilize and take action: serfs, peasants, artisans, and members of the lower nobility. Their armies engulfed regions across Germany with armed conflict until the authorities brutally crushed the uprising. This was shortly before the first edition of The Manual on Measurement saw the light of day.

The page on view shows a projected, never realized “victory monument after vanquishing rebellious peasants.” What does the unusual design signal? Its enigmatic character allows seemingly contradictory interpretations—as both mocking the peasants’ misery and pleading that the betrayed rebels be met with compassion. Notably, the figure of the slain peasant invokes depictions of Christ as the Man of Sorrows. This unbuilt monument evidently seeks to activate the viewer, though it is hard to say how.

In the history of the Reformation, the Peasants’ War marked a turning point. Many critics saw Luther’s disobedience to Rome as having caused the uprising, even though he famously castigated the “murderous peasants.” In the years following 1525, reformers sought to secure their reformations through alliances with territorial rulers.

All over Europe, Albrecht Dürer from Nuremberg found recognition as an artistic genius. His claim to a new type of artistry is manifest in the manuals he composed to put the visual arts on a systematic and sound footing. The Underweysung is part of this set of ambitious publications. By the time of Dürer’s death in 1528, the set remained incomplete, but its parts were reprinted.

See also: 2, 10, 16

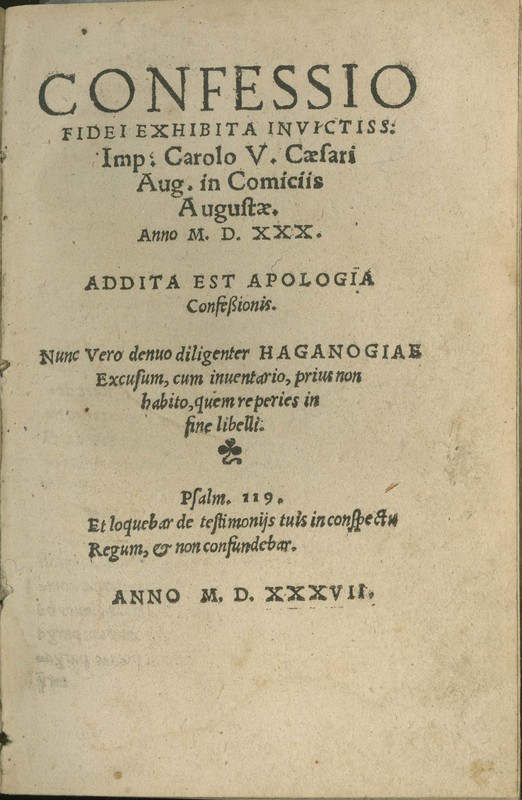

23. Philip Melanchthon, ed. Confessio fidei exhibita inuictiss. Imp. Carolo V. Caesari Aug. in Comiciis Augustae. Addita est Apologia confessionis. Hagenau: Valentin Kobian, 1537

In 1530 when Emperor Charles V called for a diet, a meeting of all the imperial estates, in Augsburg to decide, among other things, “what might and ought to be done…regarding the division and separation in the holy faith and the Christian religion,” the religious, legal, and political status of Lutherans in the empire remained an open question. John, Elector of Saxony, therefore had a document drafted to synthesize the non-negotiable positions of the Lutheran Reformation. Consisting of 21 articles of faith and seven on religious abuses, this summary of Protestant beliefs was presented at the diet. Though many formulations became mired in debate among Protestants, the Confessio Augustana (Augsburg Confession) remains one of Protestantism’s founding documents. Our 1537 edition of the Augsburg Confession reflects the controversies that preceded the diet and ensued after 1530. Published several years after the event, the pamphlet includes an “apology” by Philip Melanchthon, the main negotiator at the diet, whom fellow believers criticized for his “fainthearted” search for a religious consensus during the negotiations.

“Confessions” such as this codified core religious practices and beliefs, seeking a doctrinal unity that remained elusive. Once adopted, such documents also served to define religious difference and quell dissent in particular cities and territories.

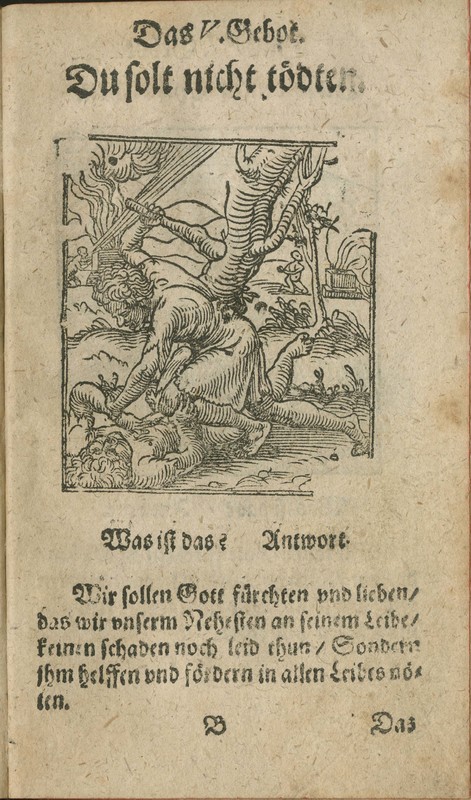

24. Martin Luther. Enchiridion: der kleine Catechismus für de gemein Pfarherr und Prediger. Magdeburg: Johann Francken, 1590

The breakup of Western Christianity into several confessions helped to give rise to a notion of religion less grounded in pious acts or what the reformers viewed as mindless observance, and more in the comprehension of relevant doctrines. The beliefs that distinguished one confession from another therefore needed to be determined, delineated, and disseminated via print and other means. The preface to Luther’s Enchiridion is typical in that it bemoans widespread doctrinal ignorance among believers. Catechetical instruction was one of the most lasting strategies in addressing this problem and spreading the theological principles of the Augsburg Confession among simple folk. Young Protestants had to memorize and recite the most basic texts of their community’s confession in schools, homes, and other venues of instruction. The woodcuts that embellish this particular edition of Luther’s innovative “Small Catechism” served as memory aids. In order to ensure religious unity, Protestant authorities launched an ensemble of printed, written, illustrated, spoken, and sung media that sought to communicate central tenets in consonance.

See also: 23, 25

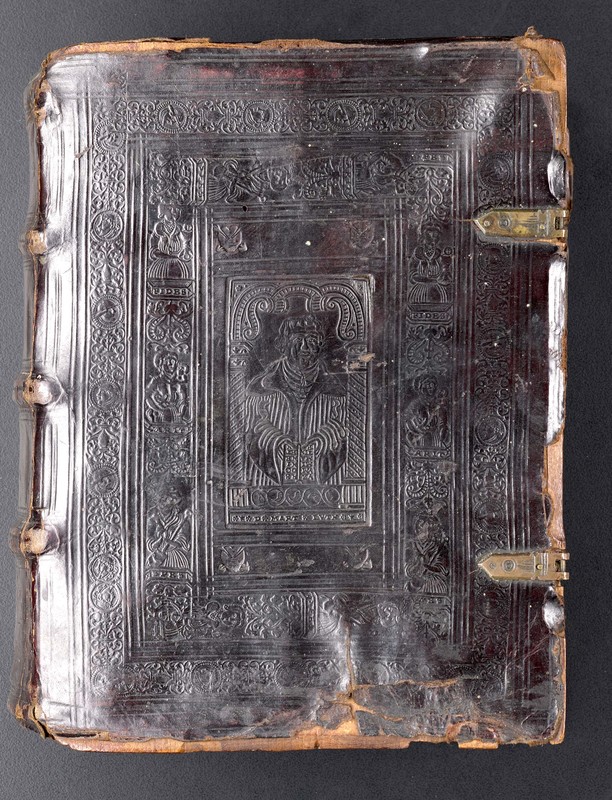

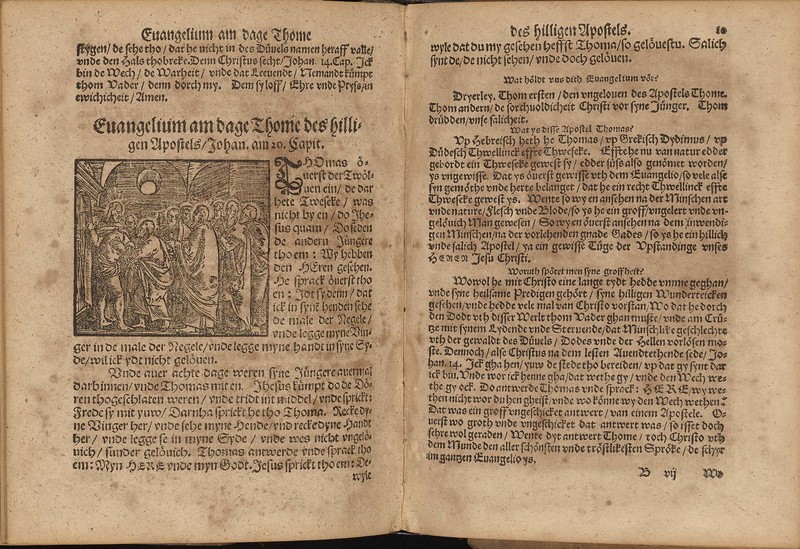

25. Johann Spangenberg. Uthlegginge der Epistelen unde Euangelien van vörnemesten Festen dorch dat gantze Jar. Magdeburg: Wolfgang Kirchner, 1589

The binding of this print features a portrait of Martin Luther imprinted in leather—one of many ways Lutherans could preserve the memory of the reformer in material objects.

Our volume is a textbook for the use of “young Christian boys and girls” in Low German— a language commonly deployed in print during this period, especially when disseminating Lutheran teachings. The pedagogue Johannes Spangenberg offers expositions on the Bible passages read during church services throughout the year. As was appropriate for his target audience, he used questions and answers—a format widespread in instructional texts of the time. The story of the Apostle Thomas who doubted the resurrection until Christ permitted him to touch the wound in his side (John 20:24-29) is explained in the text and portrayed in the woodcut represented here as a consolation for Christians whose faith still needed to be strengthened.

See also: 24

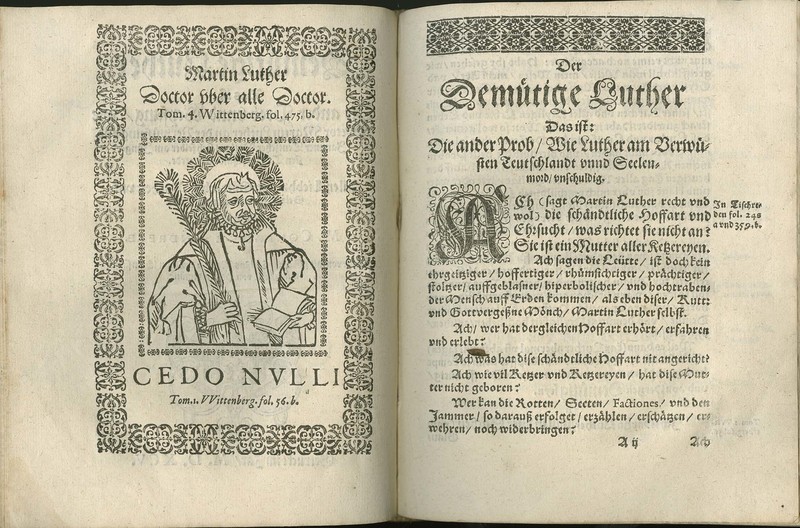

26. Conrad Vetter. Der demütige Luther das ist: Die ander Prob unnd Weysung wie Doctor Martin Luther an der Verwüstung und Jammer Teutscher Nation sich selber am Jüngsten Tag entschuldigen werde. [Ingolstadt: Wolfgang Eder] 1595

This rare anti-Lutheran pamphlet by Catholic Conrad Vetter attacks the reformer several decades after his death, above all for his megalomania. Excerpts from Luther’s Table Talks are rendered in a large font, then dissected from a polemical viewpoint in a small font. The Humble Luther, as the pamphlet’s title translates, is thus revealed as an arrogant wolf in a humble sheep’s clothing, responsible for The Devastation and Woes of the German Nation, to quote the title further.

The polemical likeness that accompanies this treatise shows no resemblance to the other known portraits of the reformer. It is a composite image, as if Luther had no true character, with iconographic allusions to a false saint. Upon close inspection, we see that instead of the palm frond typically held by saints, this un-saintly Luther carries a peacock feather and sports a patterned peacock halo. The mottos that bracket this “portrait” reiterate the text’s allegations of pride and vanity—“Doctor above all other Doctors” and “I yield to no one.”

This recently acquired Sammelband, or a volume with several prints bound together at a moment in the past, once belonged to the library at Thierhaupten monastery near Ingolstadt, where our pamphlet first appeared in print. This Bavarian town emerged as an important center of the Catholic Reformation in the sixteenth-century empire.

See also: 25

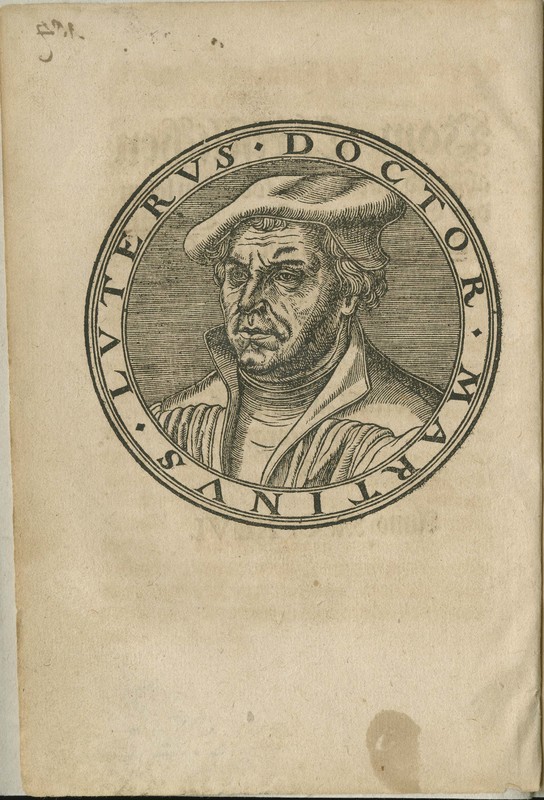

27. Justus Jonas. Vom Christlichen abschied ausz diesem tödtlichen leben des Ehrwirdigen Herrn D. Martini Lutheri. Wittenberg: Georg Rhau, 1546

Luther’s death was a public and well-publicized event. Fellow reformers published detailed accounts of his last days—such as the one on show, printed not long after his death at the age of sixty-three on February 18, 1546. At the time, two artists portrayed his countenance in death and another sculpted a death mask so that others could catch a glimpse of the dead reformer for themselves. After all, Catholic polemicists had frequently defamed Luther as a devilish figure whose true character would become evident in the hour of death. This printed eyewitness account of Luther’s passing by close associates of the reformer, sought to dispel such defamatory notions. Instead, the authors describe Luther’s death as blessed and exemplary: “When a man considers…God’s word in his heart and dies while doing so he passes before he becomes aware of his dying,” that is he dies peacefully.

The frontispiece, with its heroic likeness in a medallion, is in keeping with the monumental images of a heroic and mature Luther that visual propagandists circulated in the sixteenth century. Luther’s life and bodily presence have always been important to Lutheranism, even if many of the images reproduced today give priority to a different Luther, namely the young reformer of Cranach’s first portraits from the early 1520s.

See also: 25, 26

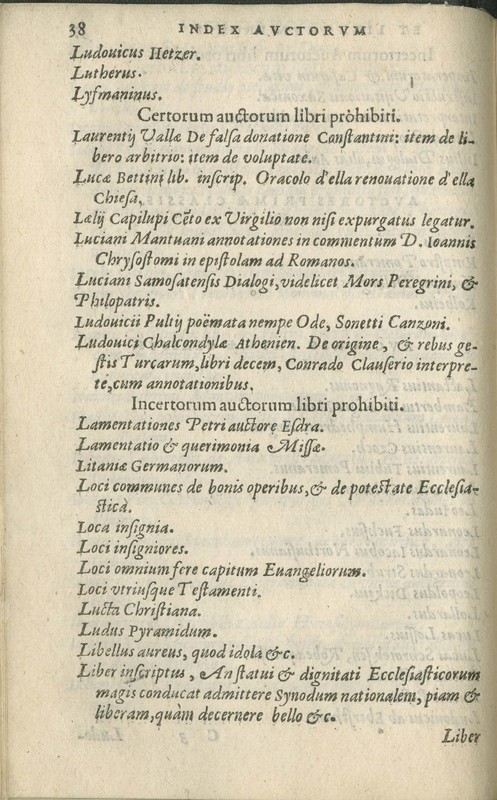

28. Index librorum prohibitorum. Antwerp: Christophe Plantin, 1570

As our exhibition demonstrates, the age of religious reforms brought an unprecedented upswing in the spread of printed publications. The medium thus became “an agent of change,” to use Elizabeth Eisenstein’s classic formulation, as printing allowed, among other things, the spread of ideas contrary to those held by religious or secular authorities. As a result, officials took measures to control the output of prints and their market.

Indices are lists of publications condemned by the Catholic Church as unorthodox or immoral, and to print, sell, or own such volumes was punishable in Catholic territories. This particular index appeared in the Low Countries in the wake of the Council of Trent, the church council that launched the reform of Catholicism often known as the Catholic or Counter Reformation. Several indices emerged in the sixteenth century across several locations before Rome took the lead and centralized these efforts in reigning in religious heterodoxy.

The publisher of this volume, Christophe Plantin of Antwerp, was widely admired for an impeccable standard of the prints issued from his shop. He was also one of the sixteenth century’s foremost Catholic printers. We show the page where Luther’s name appears in an alphabetic list as an author whose works were condemned wholesale. The two pages open to view also demonstrate how difficult it was to control the market when short titles of publications were ambiguous and the identification of titles with particular print items on the index was anything but straightforward.

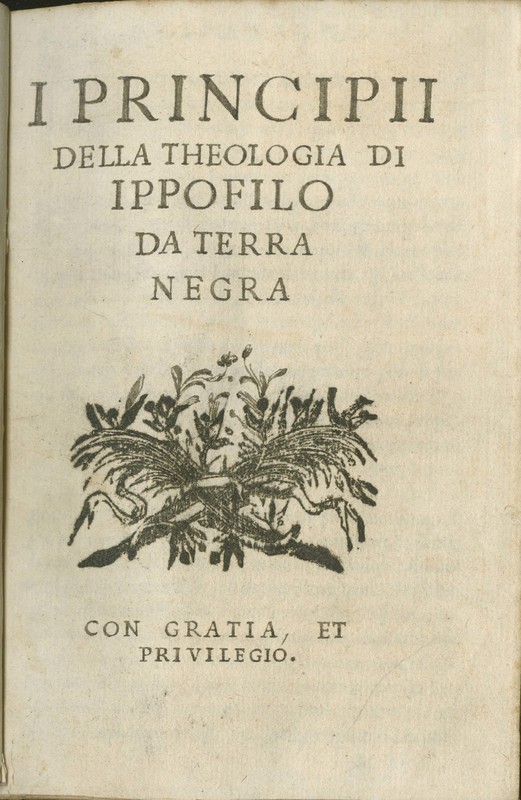

29. Philipp Melanchthon. I principii della theologia di Ippofilo da Terra Negra [pseud.] [Venice: after 1521]

As this unassuming volume vividly demonstrates, reform ideas also made inroads in Catholic Europe. It is an Italian translation of Philip Melanchthon’s Loci communes, the first and most prominent textbook of Protestant theology in the sixteenth century. Published in an undisclosed location, most likely in Venice, the book appeared in print without authorization, despite the “cum gratia et privilegio” of the title which suggests otherwise. In order to avoid censorship, the publisher obfuscated the volume’s Protestant author, though his name could be decoded easily. The Ippofilo of the title is an anagram for Filippo, while “da terra negra” (of black earth) is a literal translation of Melanchthon’s surname into Italian. Schwarzerde or “black earth” was his family’s German name, which translates as Melanchthon in Greek, a self-fashioning common among humanists, though usually through recourse to Latin and not, like in Melanchthon’s case, to Greek.

See also: 15, 23

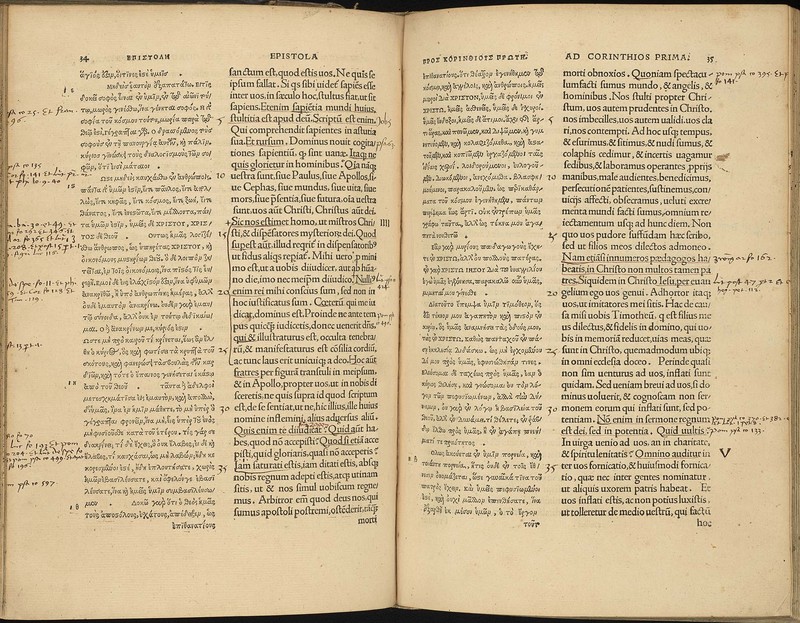

30. Erasmus of Rotterdam. Novum instrumentum omne, diligenter ab Erasmo Roterodamo recognitum & emendatum. Basel: Johann Froben, 1516

“Above all, one must hasten to the sources themselves, that is, to the Greeks and the ancients,” wrote Erasmus of Rotterdam, the foremost philologist of his age, in a 1511 manifesto on humanist learning. Five years later, he published the first modern edition of the Greek New Testament (a parallel undertaking in Spain notwithstanding), together with his own Latin version and annotations on the traditional Vulgate translation. Erasmus used his considerable skills as a scholar and editor, consulting many manuscripts, to generate a reliable version of this singularly important text, which he titled the Novum Instrumentum. Despite the edition’s flaws, which subsequent scholarship soon improved upon, the “New Instrument” was a landmark in biblical scholarship. The 1,200 copies of the first edition became an immediate success. Martin Luther used the second edition, re-titled “New Testament” (1519), for his September Testament (1522), and Tyndale consulted the third (1522) for his 1525 translation into English. Erasmus, who remained Catholic throughout his life and never authored a vernacular work, wrote in 1516 “I absolutely dissent from those people who don’t want the Holy Scriptures to be read in translation by the unlearned…Christ wanted his mysteries to be disseminated as widely as possible. I should prefer that all women, even of the lowest rank, should read the evangelists and the epistles of Paul and I wish these writings were translated into all the languages of the human race.”

See also: 1, 5, 6, 7, 31, 32

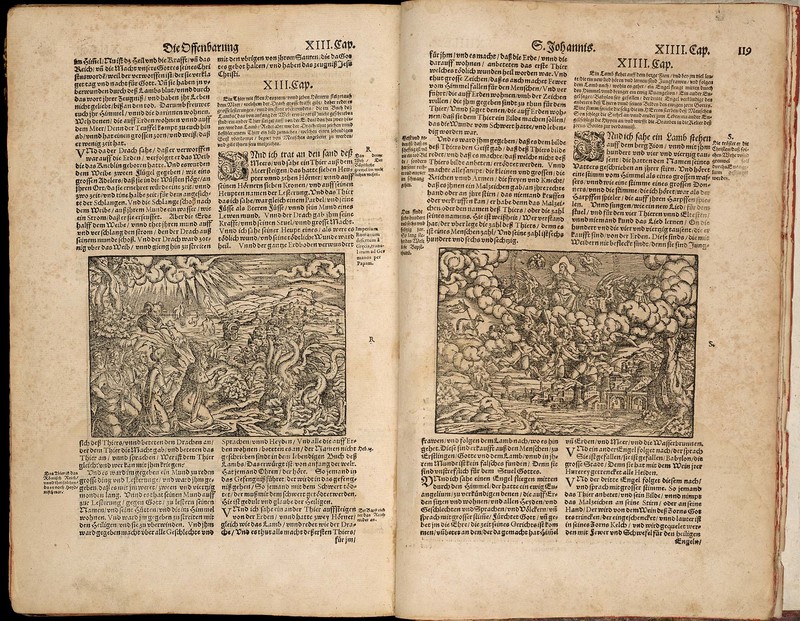

31. Martin Luther. Biblia, das ist: Die gantze Heilige Schrift, teutsch. Frankfurt am Main: [Johann Feyerabend] 1585

Luther’s translation was not the first Bible in German. Eighteen such Bibles, if not more, were available before Luther’s complete Biblia saw the light of day in 1534. The first such text came from Strasbourg in 1466, not long after Gutenberg’s epochal prints of the Latin Vulgate (B42, B36). With 13 editions, the 1466 translation had a long afterlife. This wide circulation of Bibles in the vernacular was a distinguishing feature of German-speaking Europe.

Unlike its predecessors, Luther’s Biblia did not rely on the Latin Bible used in the medieval church. By contrast, he and his helpers—Philip Melanchthon, Matthew Goldhahn, and others—based their translation on the original Hebrew and Greek texts. Yet while returning to the sources, Luther nonetheless aimed at producing a Biblia Deudsch that was eminently readable. “For the literal Latin is a great hindrance to speaking good German,” Luther noted in 1530. In fact, Luther took advantage of different approaches when rendering Scripture in German—a flexibility that helped turn his translation into a milestone in biblical exegesis. Arguably, no other Bible translation has been as successful as his, with the exception of St. Jerome’s Vulgate. Luther’s text not only left a deep imprint on German as a language but also provided a model for many other vernacular translations published in its wake.

This 1585 edition of Luther’s Biblia from a prominent Frankfurt printer is a splendid edition in folio format. Several artists amply illustrated the text, especially the Old Testament Book of Genesis and the Book of Revelation. At the same time, prefaces to different books, marginalia, and chapter introductions prepare readers for the challenging task of engaging the Book of Books on their own.

See also: 1, 7, 30

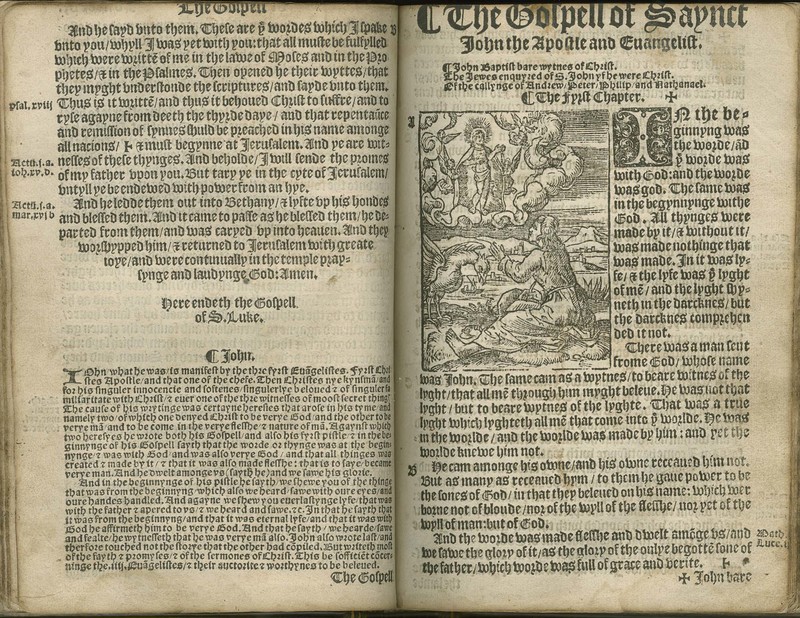

32. William Tyndale. The Newe Testament yet once agayne corrected by Willyam Tindale. Antwerp: [M. Crom] 1536

This edition of the New Testament appeared in print in the same year that William Tyndale was executed as a heretic. Translating or owning an English Bible became a crime punishable by death in England after John Wycliffe’s Bible had spread among readers in the early fifteenth century. Failing to find patronage in England for a new translation, Tyndale left for the continent. As a humanist, Tyndale drew on the Bible’s original languages as well as on Luther’s translation. After 1525/1526, copies of his edition of the New Testament in English, printed on the continent (like ours from Antwerp) but in a font and layout familiar to English eyes, were subsequently smuggled to England where they found an eager readership.

Though our copy is not in perfect condition, it still conveys the beauty of this edition, namely its striking initials, woodcut illustrations, and elaborately ornamented contemporary leather binding. If you compare this text with the many examples of continental book design in the exhibit, you will notice differences.

See also: 30, 31

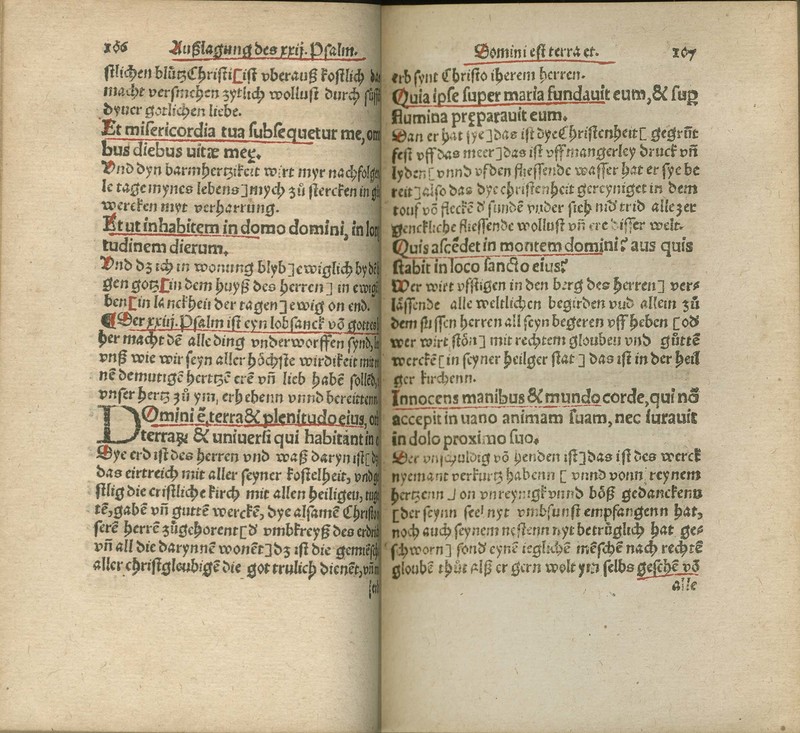

33. Der Psalter latein und teutsch. Cologne: 1535

Use of the vernacular in religious contexts was not exclusive to Protestants. Catholics in the German lands also issued German Bibles, some of them adapted from Luther’s own translation as the reformer noted with glee. Still, reading religious texts never acquired the significance among Catholics that it had for Lutherans or other Protestant groups. Among other things, the confessions differed in how, when, and why they deployed the vernacular.

The Latin and German Psalter on display here, published in Cologne—one of the few large imperial cities that remained Catholic—exemplifies this difference aptly. It is not a stand-alone translation; rather, the editor, Dierick Loer of the Carthusian order, offered a German psalter that paraphrases and explains the traditional Latin psalms passage by passage. Importantly, our publication seeks to work against the perception that it is a new or unauthorized text, instead inscribing this German Psalter in Carthusian traditions and linking it to a monastic setting for nuns.

Media. Effects.

Glossary