Media. Effects.

This superb map was drawn up by Abraham Ortelius, one of the pioneering Renaissance cartographers, and shows the “Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation” as a united polity. This rendering notwithstanding, its many cities and territories, both small and large, formed a political patchwork with the emperor at the top. While political reforms had recently strengthened the empire’s central administration, political fragmentation persisted, allowing religious diversity to flourish and the Reformations to emerge, which led to more political fragmentation.

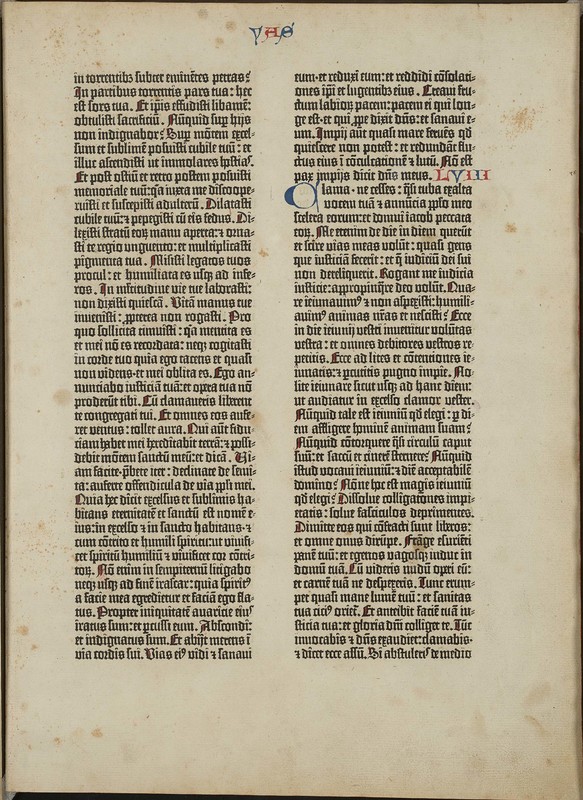

1a. Biblia Latina [42 lines] (fragment, 1 leaf) [Mainz: Printer of the 42-line Bible (Johann Gutenberg and Peter Schoeffer), c.1455]

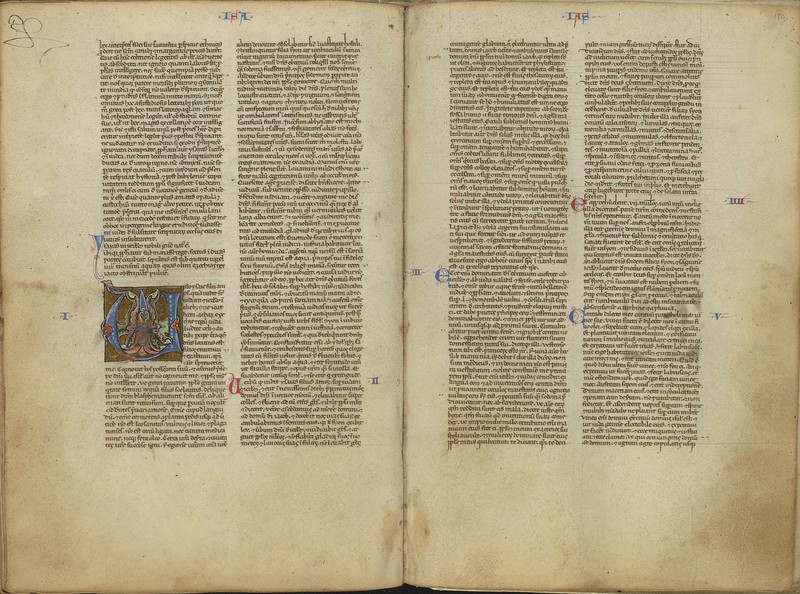

1b. Biblia Latina s.XIII (France?)

Early printing was a technology of staggering complexity. People of various skills—entrepreneurs, artisans, laborers, scholars, and others—teamed up to sell multiple identical copies of the same text, produced through a labor-intensive process. When Johannes Gutenberg invented printing in the 1440s, his invention involved various interlocking elements, among them an instrument for manufacturing identical movable types made of a particular alloy, an oil-based ink suited for movable metal types, and a press used to distribute the ink evenly on the surface. Setting one printed page could take a skilled typesetter a day of work. Printing the 1,282 pages of the Vulgate, the Latin Bible, took about 20 people more than two years. It is estimated that up to 200 copies of Gutenberg’s B42, named after the 42 lines of text in each column, were initially printed. Some were printed on vellum (animal skin), but most were produced on paper of which fewer than 50 copies survive, many in fragments—like ours.

In the beginning, printed books were roughly as expensive as manuscripts of the same text. The comparison of a Bible manuscript in Latin from the thirteenth century (probably written in France) and a page from Gutenberg’s first printed Latin Bible from the early 1450s shows that prints were simply ‘better manuscripts.’ In general, the appearance of a printed page is strikingly regular, lacking the variations of a written hand and therefore beautiful. Books like the B42, printed in the fifteenth century, are conventionally called incunables (incunabulum/incunabula), meaning that they were printed ‘in the cradle’ (in cuna) of printing history. Many features of the book—its structure, its layout with running titles, margins, index, scripts, ornamentation—persisted through this period of radical change in the dissemination of texts.

See also: 19, 31, 32, 33

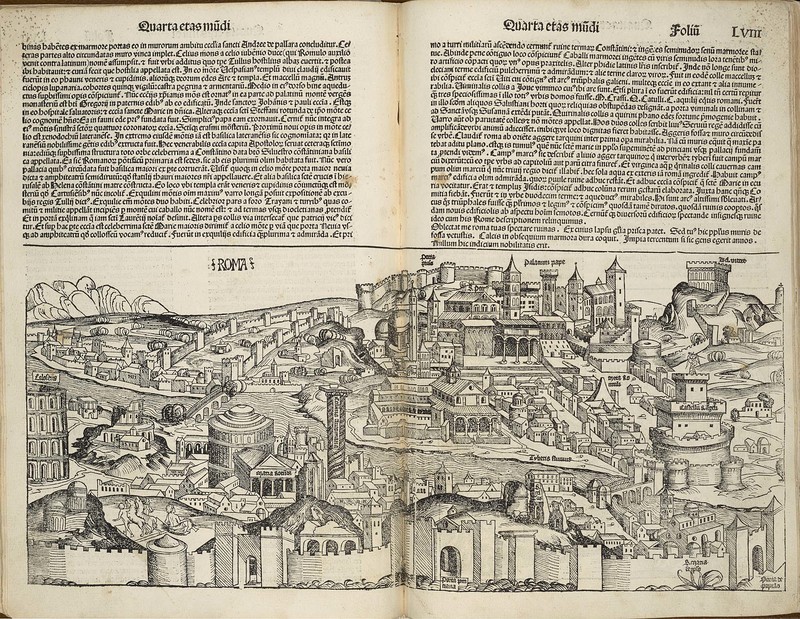

2. Hartmann Schedel. Liber chronicarum. Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, for Sebald Schreyer and Sebastian Kammermeister, 12 July 1493

Approximately fifty years after the medium’s inception, the Liber chronicarum (Book of Chronicles), also known as the Nuremberg Chronicle, showcases the ‘art of printing’ at its best. The book amounts to a digest of everything there was to know about the world in one volume. We have ample documentation on the making of the chronicle from Nuremberg, one of the most populous and industrious cities in the German empire. The local humanist and medical doctor Hartmann Schedel compiled the text, which was immediately translated into German. A great many people of various skills oversaw the volume’s complex production. In 1511, 400 Latin copies of a print run of 1400-1500 were still on stock, while the German volume had almost sold out with only 60 copies remaining.

Importantly, the chronicle appealed to buyers and readers with its lavish illustrations. 652 different woodblocks were used, while 1804 illustrations adorn the volume, either in black and white—as in our copy—or colored. Through both text and image, the novel city portraits invited armchair traveling and informed readers about geographically distant, past, and foreign places. Among these, the view of Rome, the papal see, is one of the most splendid, capturing an urban topography with significant ancient and spiritual associations.

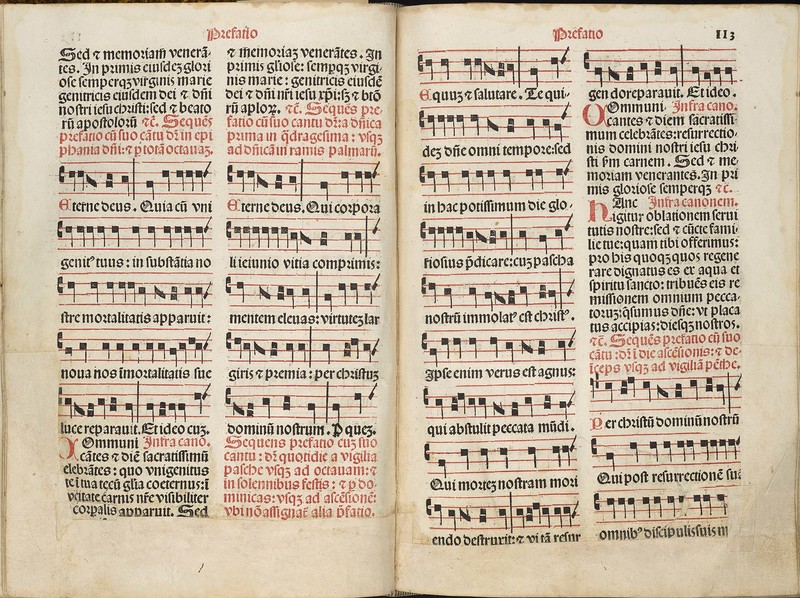

3. Missale Romanum. (Ed: Petrus Arrivabenus?) Venice: Georgius Arrivabenus, 29 May 1499

Textual precision and liturgical standards mattered to the Church.

For example, ecclesiastical authorities had a strong interest in issuing model liturgies for performing services of different kinds. This impressive volume is not destined for a specific diocese; rather it served as a missal for Catholic Christianity in general. It is distinguished by its large size which facilitated its use by choirs during service, its extensive musical notation, and its sophisticated use of red ink to orient users. Printing musical notation had emerged approximately 25 years earlier and was put to excellent use in our Roman Missal.

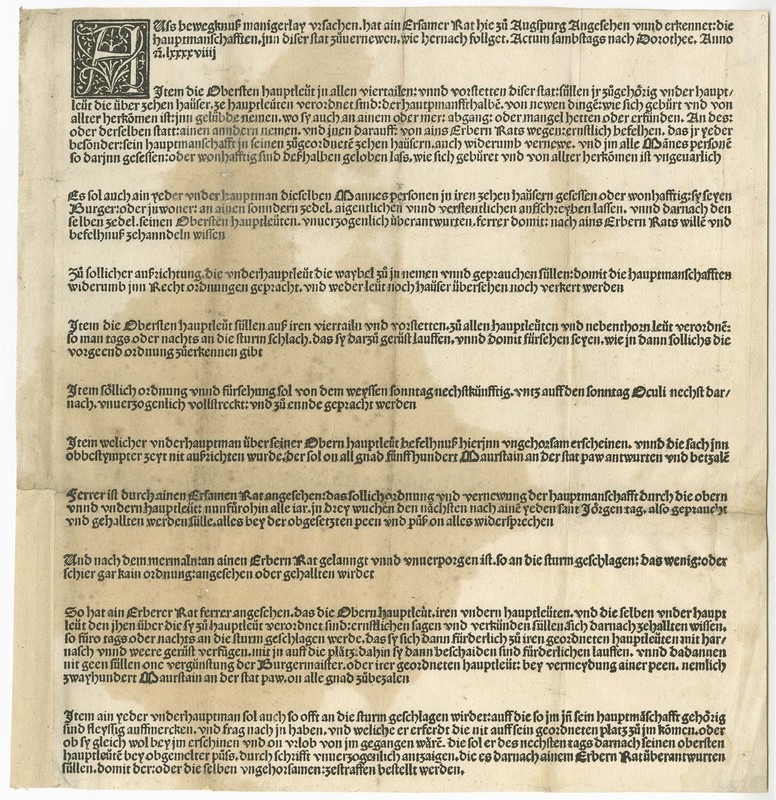

4. Wehrordnung, herausgegeben vom Rat der Stadt Augsburg, 9 Feb. 1499 [Augsburg: Erhard Ratdolt, after 9 Feb. 1499]

Church and secular authorities used print, once it became available, to communicate with believers and subjects. In the case of this single-leaf broadsheet, the council of the city of Augsburg published a mandate that updated extant regulations regarding its defense forces—a task shared by all citizens. As one of the regulations makes clear, there should be a captain for every ten houses in a lane. Among other things, military leaders were asked to instruct the men in their respective units about what was expected of them. The council thus tried to ensure that the mandate’s content would reach an urban audience since not everyone was able to read, though literacy was common in this milieu.

One-page prints were often posted in public places where many residents could see them. Although some broadsheets featured images, most single-leaf prints were like this one—text only with an initial as its only ornament. The mandate’s print run amounted to 420 copies, as is testified in the official record of the printer’s remuneration. Of these, only two broadsheets survive to this day.

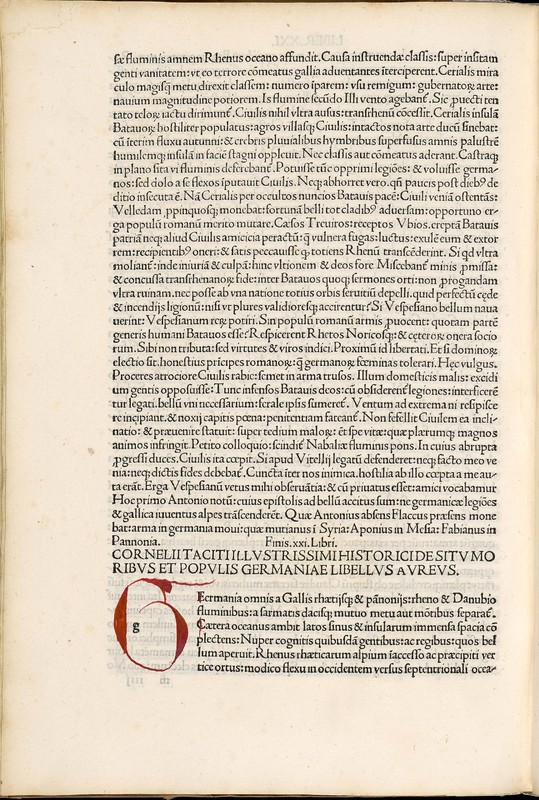

5. Gaius Cornelius Tacitus. Opera. Ed: Franciscus Puteolanus and Bernardinus Lanterius. Venice: Philippus Pincius, for Benedictus Fontana, 22 Mar. 1497

Humanist scholars took pride in publishing texts whose existence had fallen into oblivion, especially those from ancient times. One of the most celebrated discoveries in this vein was the Roman historian Tacitus’s Germania (98 CE)—a sympathetic account of a foreign people that is almost without parallel in the Roman literary canon. The text was re-discovered in 1455, and its publication ushered in a wave of enthusiasm for Germanic antiquity. The proto-nationalist celebration of German honesty, simple manners, and straightforward virtue contributed to an imaginary that allowed for a break from Rome.

The copy on view is an anthology of several works by Tacitus, with the page open to where the text of the Germania starts. It is a perfect example of humanist book design, as its Roman or Antiqua font mimics a script used on ancient monuments, appropriate for such an edition of a Roman author. This font became widely used in prints of this period as other authors and printers sought to emulate antiquity.

See also: 6

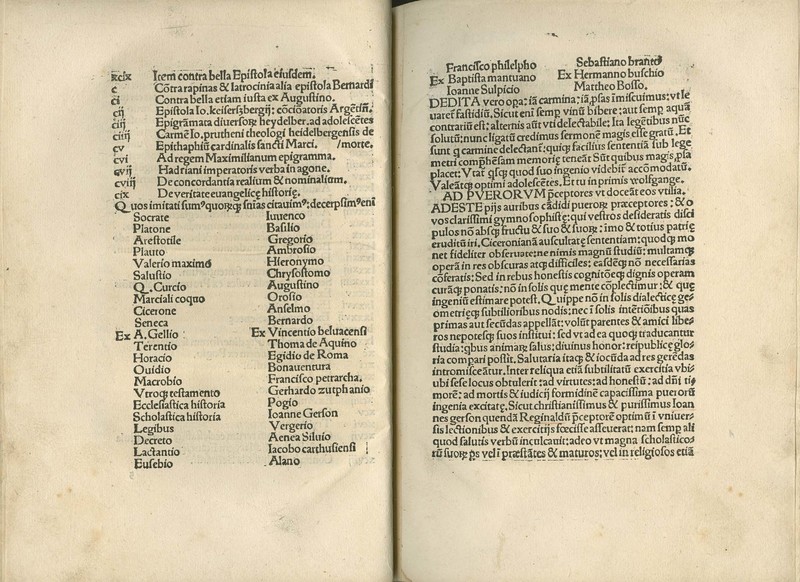

6. Jacob Wimpfeling. Adolescentia. Strassburg: Martin Flach, 27 Aug. 1500

Useful knowledge was the humanist shibboleth to re-structure processes of learning on all levels, and this rare first edition of Youth illustrates the pedagogical impetus of early humanism. The idea of utility centered above all on the study of ancient languages, and humanists like our author, Jacob Wimpfeling, claimed that learning Latin provided access to vast resources of knowledge and ethical teachings whose practical application would improve the present state of affairs. Our treatise, one of three publications of his on education, is a Latin textbook for use in class by both teachers and advanced students—a pedagogical practice made easy by the medium of print. The open pages list writers Wimpfeling deemed worthy of an adolescent’s study. Interestingly, in addition to Roman authors, recommended readings include church fathers, medieval writers, and Renaissance scholars, reflecting an eclecticism characteristic of some strands in Christian humanism.

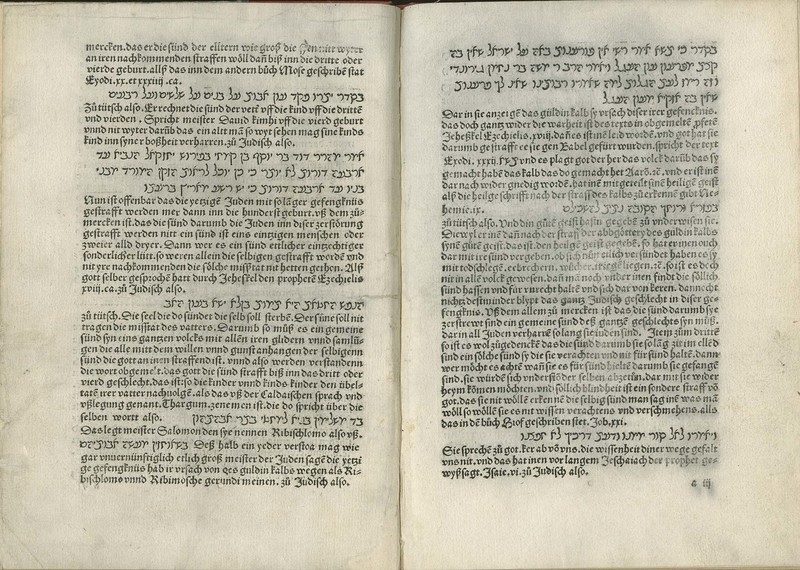

7. Johann Reuchlin. Doctor Iohanns Reuchlins tütsch Missiue. Warumb die Juden so lang im Ellend sind. Pforzheim: Thomas Anshelm, 1505

This short treatise was written by the foremost Christian scholar of Hebrew in early modern Europe, Johannes Reuchlin, and printed by Thomas Anshelm. Its German text features many passages in Hebrew—a language rarely before seen in print, at least north of the Alps—for his target audience, Jews.

Having established close ties with Jewish scholars, Reuchlin studied ancient Hebrew to gain novel insights into the Bible. He is widely known for having defended Jewish learning in one of the most significant controversies prior to the German Reformation. In 1509, a Jewish convert to Christianity named Johannes Pfefferkorn launched a campaign—backed by Emperor Maximilian I—to have all Jewish books confiscated and burned with the express intent to promote the conversion of Jews to Christianity. Reuchlin spearheaded the response to and resistance against this plan in several highly successful publications.

In our 1505 German-Hebrew booklet, however, we encounter a different Reuchlin. Through mutual dialogue rather than the use of force, he calls on Jews to explore why God had punished them for their sins for so long and consider conversion. One year after Reuchlin’s Missiue (Open Letter) was published, Reuchlin and Anshelm collaborated once more on De Rudimentis Hebraicis—a grammar that would inform the study of Hebrew among non-Jewish scholars for generations to come.

8. Girolamo Savonarola. Epistola fratris Hieronymi de Ferrara ordinis praedicatorum in libros de simplicitate Christianae vitae. Florence, 1509

The period prior to the Reformation was ripe with religious unrest. All over Europe, new ideas on how to practice one’s faith sprang up within the church. In fact, many clerics and laypeople pursued ways to heighten their religious experience. Among the most influential figures in this regard counts the Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola, who galvanized the Republic of Florence with his apocalyptic messages. In sermons and writings, he prophesied the coming of a New Jerusalem, but only once Florentines abandoned their pursuit of civic and personal wealth in this rich mercantile center for spiritual gain. For four years, his religious program held sway over politics and religion in the city; but when the public turned against his prophesies, he was burned at the stake.

Many reformers of different persuasions embraced the notion of religious renewal through a return to apostolic simplicity in light of the coming end of times. In fact, Luther came to see Savonarola, who dared to cross the pope’s political designs, as a precursor of his own reforms, which were also centered on biblical ideals. In this particular work, Savonarola marshals the figure of Ruth as a model for virtuous behavior and simple faith. The main message of this volume, simplicity, is echoed in the book’s makeup with its small size and simple title page. In fact, this is one of the few posthumous publications of Savonarola’s works to come out of Florence where authorities were wary of the friar’s legacy.

See also: 13

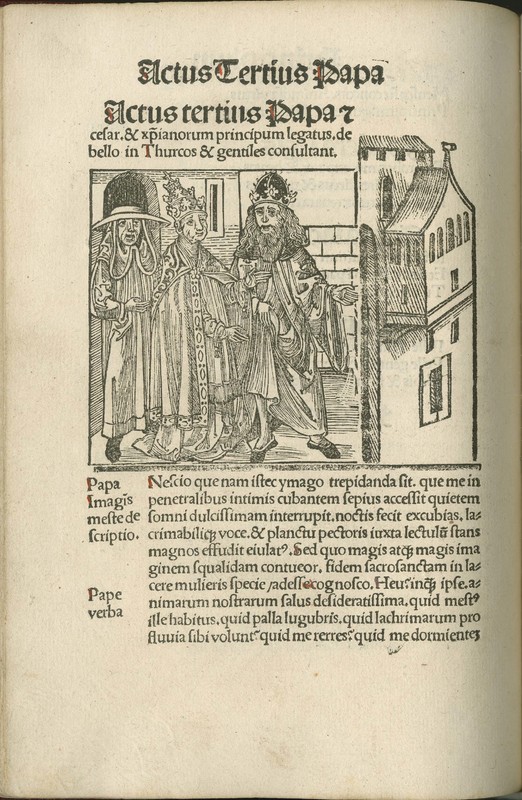

9. Jacobus Locher. Panegyricus ad Maximilianum. Tragoedia de Turcis et Soldano. Dialogus de heresiarchis. Strassburg: Johann (Reinhard) Grüninger, 1497

Print provided an ideal venue for imperial propaganda. Emperor Maximilian I supported a vast network of poets, publicists, professors, and others who in different genres and ventures promoted his rule—a rule characterized by vast political ambitions, frequent warfare, and persistent conflicts with other powers.

In 1497, Maximilian bestowed the title of poet laureate on 26-year old Jakob Locher, and in response, Locher’s Panegyricus portrayed Maximilian as a ruler with a mission to save Christian Europe from the so-called ‘Turkish threat.’ Locher counted among the most celebrated humanists and poets of his time. Educated at German and Italian universities, he was the author of two publicly performed Latin plays on contemporary politics.

The particular chapter on view shows the pope and emperor along with a delegate of other Christian powers uniting forces against Ottoman conquests. This vision is far from what actually transpired. During this period, political alliances in the face of military and other threats from the outside became ever more remote. Despite growing rifts and mounting tensions, Locher portrayed church and secular leaders working side by side—even if only in print.

See also: 7, 10, 14

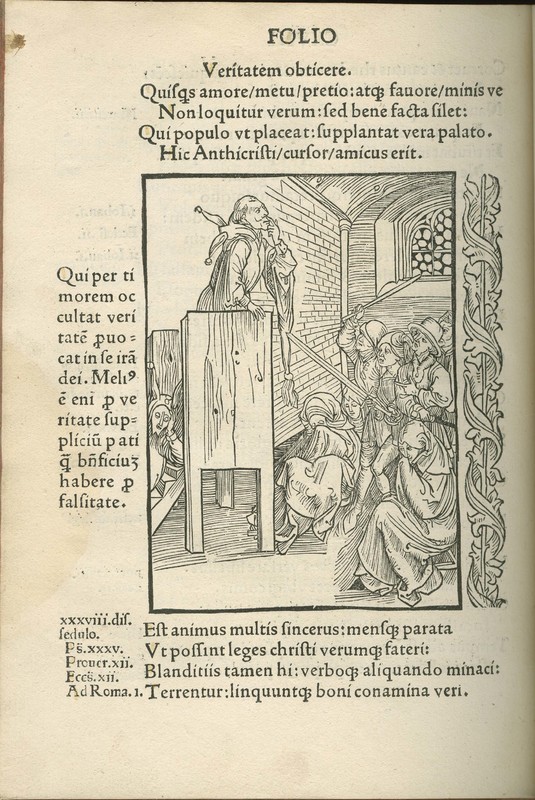

10. Sebastian Brant. Das Narrenschiff [Latin] Stultifera navis. Tr: Jacobus Locher Philomusus. Basel: Johann Bergmann von Olpe, 1 Mar. 1497

The Ship of Fools was an early modern bestseller. At least 69 editions, some of them unauthorized, saw the light of day between the first edition of 1494 and 1600. Its author, Sebastian Brant—a lawyer, humanist, and dean at University of Basel—collaborated with printers on various occasions. In 1494, he and Johann Bergmann von Olpe launched a novel genre in German: a satirical portrait of human society as an assembly of fools with each of the 113 chapters focused on a particular foible. The fool was a figure of carnival ritual as well as a symbol for man’s ignorance about God’s creation. Brant thus taught readers of various backgrounds and levels of education what to do by means of negative examples. “Well-ordered love for other men / Means; With yourself you must begin.”

The book’s tremendous success relied above all on its 1497 adaptation into Latin by Brant’s student, Jakob Locher. The Latin edition provided a basis for disseminating the Ship of Fools in Dutch, English, French, and other vernaculars. Every chapter contains a title, illustration, epigrammatic synthesis, and poetic exposition of a certain weakness or sin. The one on display teaches that whoever occludes the truth performs the work of the Antichrist. The Ship of Fools’ learnedness notwithstanding, the woodcuts, many of them by the young Albrecht Dürer, signaled to readers that the message was accessible. In this and in other chapters, however, text and image do not conform entirely.

See also: 2, 9, 22

11. Ulrich Pinder. Speculum passionis Domini nostri Iesu Christi cum textu quatuor evangelistarum. Nuremberg: Friedrich Peypus, 1519

In the German lands, as elsewhere in Christian Europe, the imitation of Christ became one of the preferred paths for believers searching for a piety replete with spiritual rewards. After all, the bodily sufferings during the Passion showed the savior at his most human. Christ’s humanity provided ample occasions to inspire compassion, contemplation, meditation, and reflection. Publications such as Ulrich Pinder’s oft-reprinted Speculum passionis domini (Mirror of the Lord’s Passion), whose first edition dates to 1507, incited their readers to follow Christ through devotional practice. In our edition, woodcuts by Hans Schäuffelein, a student of Dürer, serve as visual aids in stimulating one’s pious engagement. In this magnificent illustration of Christ before Caiaphas, the Jewish high priest resembles an ecclesiastical dignitary and his hat a bishop’s miter. A sixteenth-century reader responded by deliberately and carefully defacing the same figure. We may not be far off the mark interpreting this as a critique of the church hierarchy. After all, such views were common among followers of the Reform message.

See also: 2, 12, 14

12. Epistola de miseria curatorum seu plebanorum [Augsburg: Johann Froschauer, 1495-1500]; Lavacrum conscientiae [Augsburg: Johann Froschauer, not after 1498]

On the eve of the Reformation, anticlerical ideas were extremely popular and widespread. The clergy’s privileges along with their role as arbiters of human behavior invited slights that showed them to be no different, if not worse, than others.

The Letter on the Wretched Condition of Curates or Priests counts among the most successful publications in this vein. Its anonymous author, while intimately familiar with clerical life, pokes satirical fun at the clergy: Nine devils plague them, supposedly, among them a female cook who tempts priests sexually and a peasantry outraged by boring sermons or long masses. Evidently, humor and instruction worked hand in hand. Whether the target audience of this satire was the laity, the clergy, or both remains an open question. At any rate, the Epistola’s organization is reminiscent of edifying texts for lay readers published during the same period with their simple mnemonic structures. At the same time, our edition of this treatise is bound together with an instructional text for clerics, the Lavacrum conscientie (The Bath of Conscience).

It is important to remember that this is not a factual portrayal, yet even in jest, the Epistola captures both the pressures priests faced from many corners and the isolation in which they often lived. After 1517, the anticlerical stereotypes evident in this and other texts validated Protestant Reformers’ polemics against Catholic clergy. Not surprisingly, Martin Luther re-published the Epistola in 1540 for a Protestant audience.

See also: 10, 11

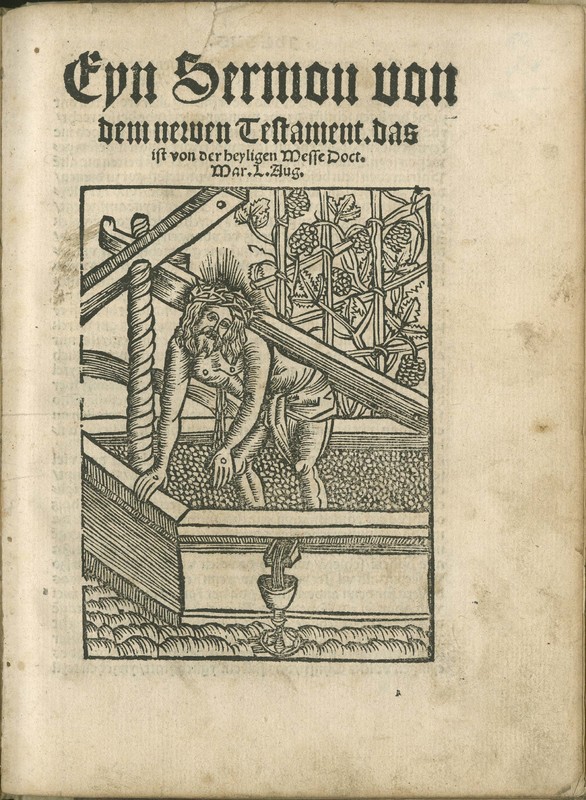

13. Martin Luther. Eyn Sermon von dem newen Testament, das ist von der heyligen Messe. [Leipzig: Valentin Schumann] 1520

In the late 1510s and early 1520s, Luther became known to many not only as a controversialist and author of the “95 Theses,” ready to break from Rome, but even more so as a pastoral theologian whose teachings in spiritual matters attracted an ever-growing audience of readers. His name—rendered on the title page of this print to attract potential buyers—became something like a brand. What is more, his name provided unity to the events we associate with the Reformation as they unfolded.

The emerging rift with Rome notwithstanding, this title page highlights the continuity between pre- and post-Reformation imagery. Based on a passage from the Old Testament prophet Isaiah (63:3) —“I have trodden the wine press alone”— the wine press emerged as a potent symbol of Christ’s suffering for mankind in the centuries prior to the Reformation. The chalice references the Last Supper, while the beams of the press invoke the cross. What is remarkable about this title woodcut is that the wine is ready for everyone, and no clerical mediators stand between the viewer-reader and the sacrament.

The visual message is very much in keeping with the warm tone of the text, in which Luther argues that the Mass is not a priestly ritual but God’s generous gift to everyone and should therefore be accessible to everyone.

See also: 16, 17, 18, 19

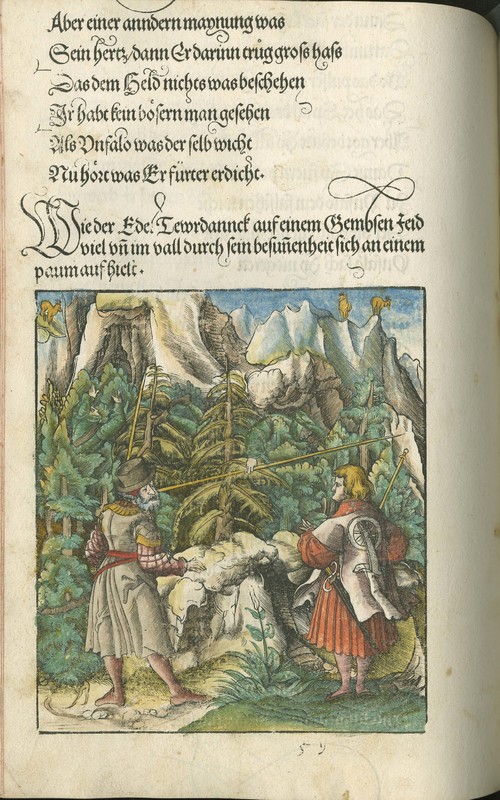

14. Maximilian I. Die Geverlicheiten und eins Teils der Geschichten des loblichen Streytparen und hochberümbten Helds und Ritters herr Tewrdannckhs. Nuremberg: Johann Schönsperger, 1517

Unlike Martin Luther’s “95 Theses,” the Teuerdank print of the same year (1517) was a luxurious undertaking. In the guise of an adventurous tale, Emperor Maximilian allegorizes his courtship of and marriage to Mary of Burgundy forty years earlier (1477). With its emphasis on the virtue of rulers, the storyteller transforms centuries-old heroic narratives into aristocratic ideals from Maximilian’s own time.

The book’s newly designed Gothic font—routinely used for German-language publications—is reflective of a calligraphic hand, though there was no manuscript edition of this text. 118 woodcuts by some of the foremost German Renaissance artists of the time adorn the volume. Their interest in representing the natural environment is evident in the exquisitely colored woodcut you see, with its detailed mountainous scene enlivened by energetically rendered animals and people.

While dissemination of texts via print is often associated with a market of anonymous buyers, the first edition of this exquisite book served as a gift to people close to the emperor. In fact, the Teuerdank was one of many ambitious artistic endeavors the emperor commissioned. With state of the art technologies and the most advanced visual-aesthetic codes of the day, the emperor used a variety of media to enshrine the memory of his rule.

See also: 7, 10

War of Words. War of Images.