A Question of Provenance: Marks from Isaac Newton's Library

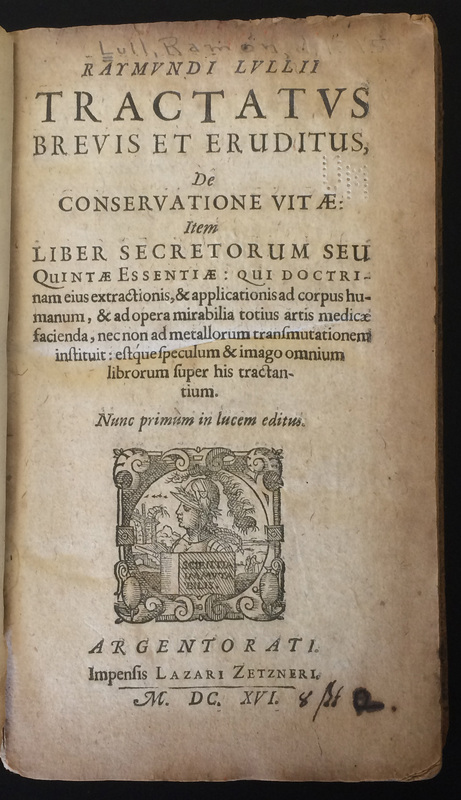

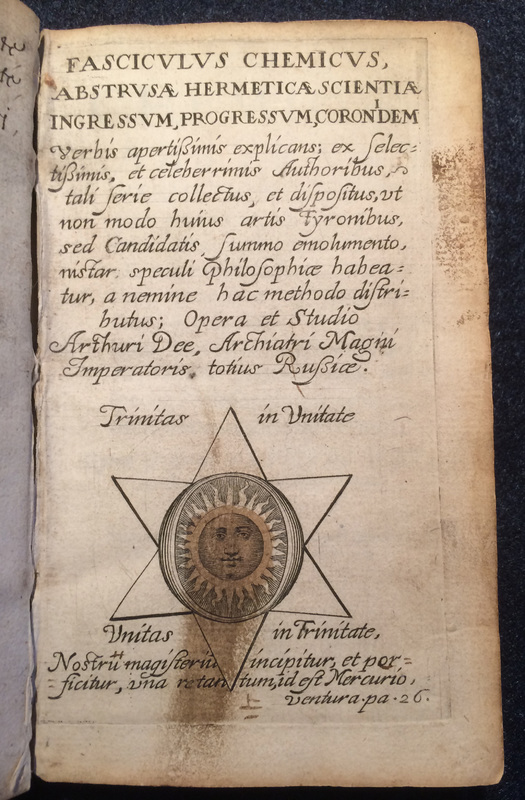

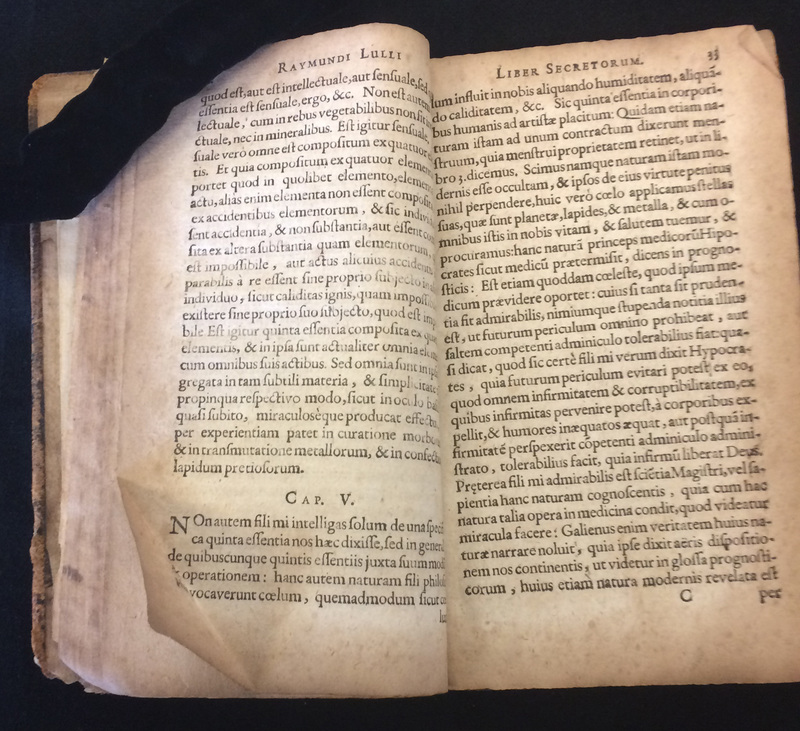

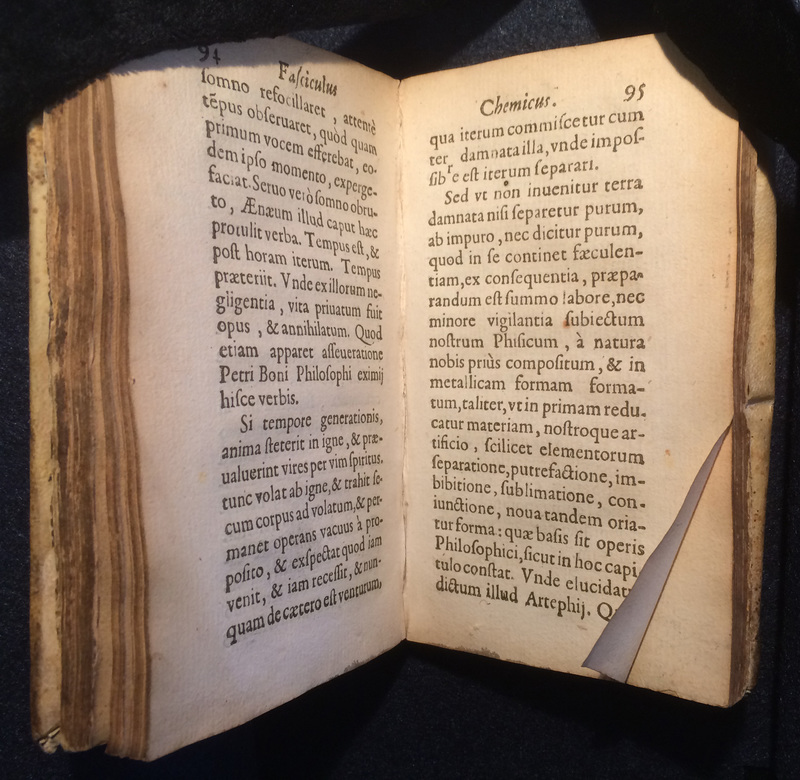

Marks in books in the form of bookplates, library's shelf-marks, or any sort of traces left by readers can reveal extraordinary information about the identity of former owners and readers of a particular book. For instance, by examining the physical evidence of these added vestiges, we are able to argue that we hold two books that were originally part of the library of Isaac Newton. The first one is titled Raymundi Lullii tractatus brevis et eruditus, De conservatione vitae; Liber secretorum seu quinta essentiae (Augsburg: Lazarus Zetznerus, 1616): they are two alchemical treatises wrongly attributed to the Majorcan philosopher and polymath Ramon Llull (Raymund Lully) (ca.1232-ca.1315). And the second one in called Fasciculus chemicus, abstrusae hermetica scientiae ingressum, progressum, coronidem, verbis apertissimis explicans (Paris: Nicolas de La Vigne, 1631), by Arthur Dee.

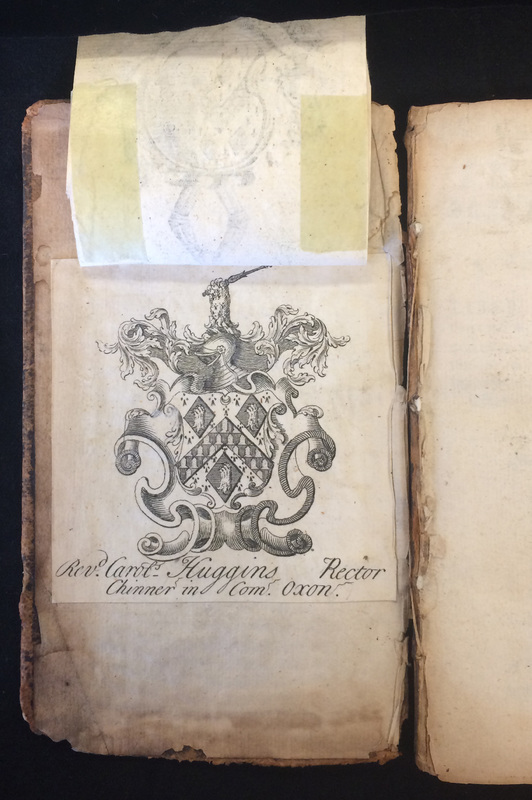

The most exact record of the library of Isaac Newton is a list created just six weeks within Newton’s death in 1727. Known as the "Huggins List," it is held at the British Library. According to this inventory, the library of Newton contained 1896 printed books along with some uncataloged pamphlets. The first purchaser of these books was John Huggins, the Warden of the Fleet Prison, who bought them for his third son, Charles, Rector at Chinnor, a village near Oxford. In all his books, Charles inserted a bookplate bearing the Huggins coat of arms and the legend, “Revd Carol(u)s Huggins, Rector Chinner in Com. Oxon.”

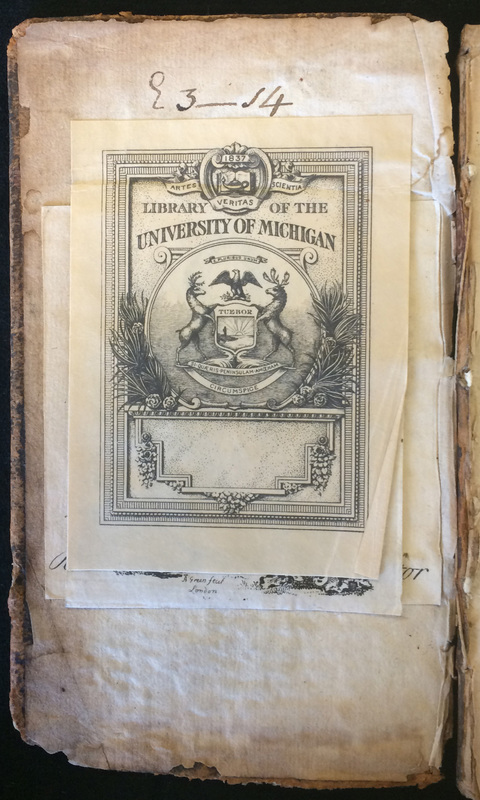

Charles Huggins died in 1750 a bachelor. His elder brother William administered the estate, giving the Rectory at Chinnor to his future son-in-law and new Rector, James Musgrave. Next, the library was sold to Musgrave for £ 400. Contrary to his predecessor in the Rectory, Musgrave fully appreciated the historical importance of the library. He created a system to record the books and opened the library to visitors. Following the original arrangement of Newton's library, the books were again shelved according to format (folio, quarto, octavo, etc). More importantly, each volume was assigned a shelf-mark written in ink. It consisted of a letter (bookcase) followed by a number (shelf), then a dash and another number (the location of the book on the shelf).

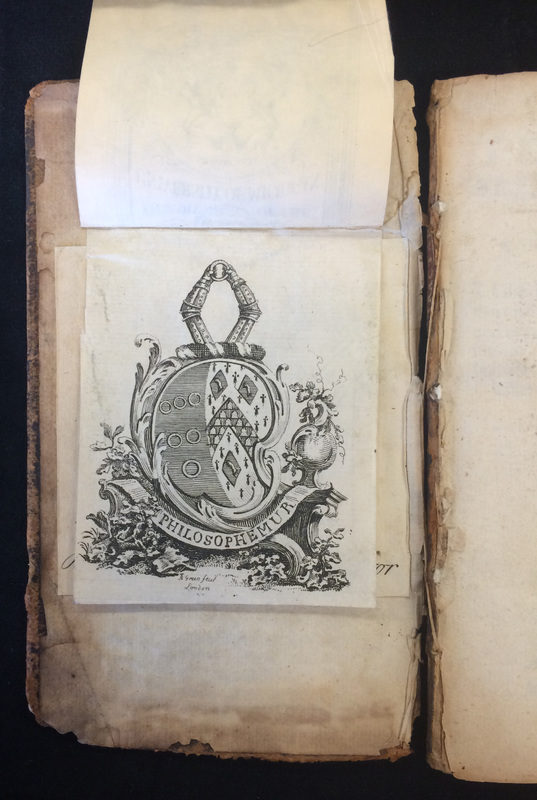

Musgrave also inserted his bookplate: a combination of the coat of arms of both families, the Huggins and Musgrave, with the Latin motto, Philosophemur ("may we philosophize"). But the Chinnor library was moved to Barnsley Park (Gloucestershire) in or shortly after 1778. The owner of that estate, Cassandra Perrot, had left the house to her nephew James Musgrave, the son of James Musgrave, Rector at Chinnor. The latter died only a month after Miss Perrot's death in 1778, so James junior inherited both Chinnor and Barnsley. A new shelf-mark was added to the books, although it is missing in our copy of the two pseudo-Raymund's treatises. The library at Barnsley Park remained very much intact, and unknown to scholars, until 1920, when Hampton & Sons auctioned a large portion of it. For many years books from this auction sale appeared in antiquarian catalogs, ending in private and institutional hands all over the world. The most recent inventory of Newton's library is John Harrison, The Library of Isaac Newton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), where 1752 separate titles have been identified.

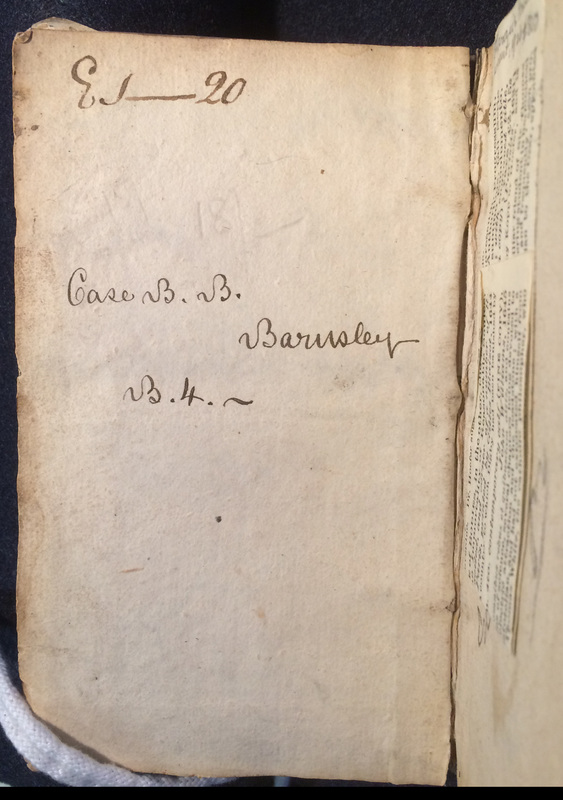

Our copy of Arthur Dee, Fasciculus chemicus, abstrusae hermeticae scientiae, ingressum, progressum, coronidem, verbis apertissimis explicans (Paris: Nicolas de La Vigne, 1631) is also very likely from Newton's library. Although it does not include any of the two mentioned bookplates, from the Huggins and Musgrave families, we can see the two familiar shelf-marks written in ink on the verso of the front endpaper.

The first, "E1-20", is the one used by James Musgrave for his books, including those purchased from Newton's library. Thus this book was shelved in bookcase E, first shelf, and it was number 20 within that shelf. Next, is the shelf-mark employed by Musgrave's son, James Musgrave, the heir of Barnsley Park. "Case B. B. Barnsley. B. 4" refers to book case, shelf, location of book on the shelf, and the main location.

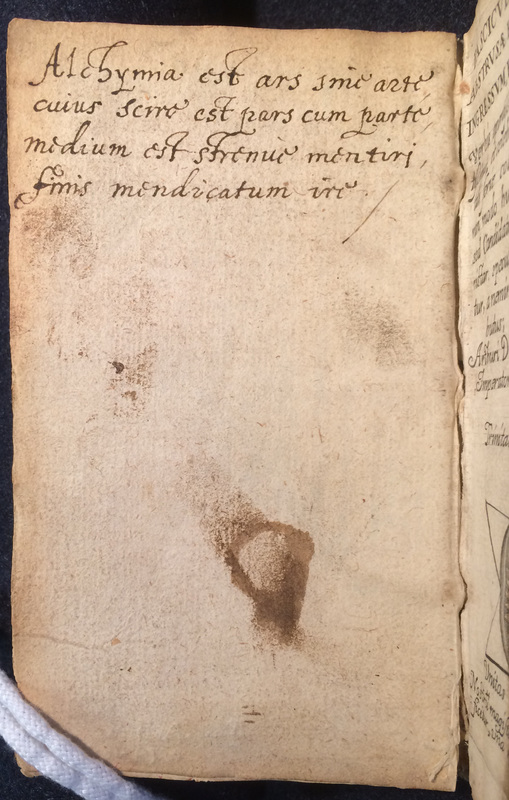

A former owner, certainly not in love with alchemy, inscribed a Latin satirical poem on the front endpaper of our copy:

Alchymia est ars sine arte

cuius scire est part cum parte

medium est strenue mentiri

finis mendicatum iri.

Alchemy is an art without art

whose knowledge is to mix part with part

its means is to lie strenuously

and its end is to became a beggar.

Evidently, those lines were not written by Newton, who was in fact very interested in alchemy. Perhaps they were written by any of the two Rectors, who found the subject offensive to the Christian faith, thus explaining the absence of a bookplate. Moreover, the debate about whether alchemy was actually a science was widely spread in the second half of the sixteenth century. For example, Thomas Moresinus (ca. 1558-ca.1603) published a strong attack against the "science" of alchemy: Liber novus de metallorum causis et transsubstantione (Frankfurt: Johan Wechel, 1593). Andreas Libavius, a doctor and firm believer in the virtues of alchemy, counter-attacked with his treatise, Singularium (Frankfurt: Peter Kopff, 1599), where he included what is likely the earliest recorded reference to the verses that would be later quoted in the inscription of our copy.

Obviously, the presence of these shelf-marks and bookplates are not conclusive proofs since they were added to all the books. However, the additional and conclusive evidence is that it is well known that Newton marked favorite passages in his books by dog-earing their pages, a practice that we can see in the two copies under discussion.

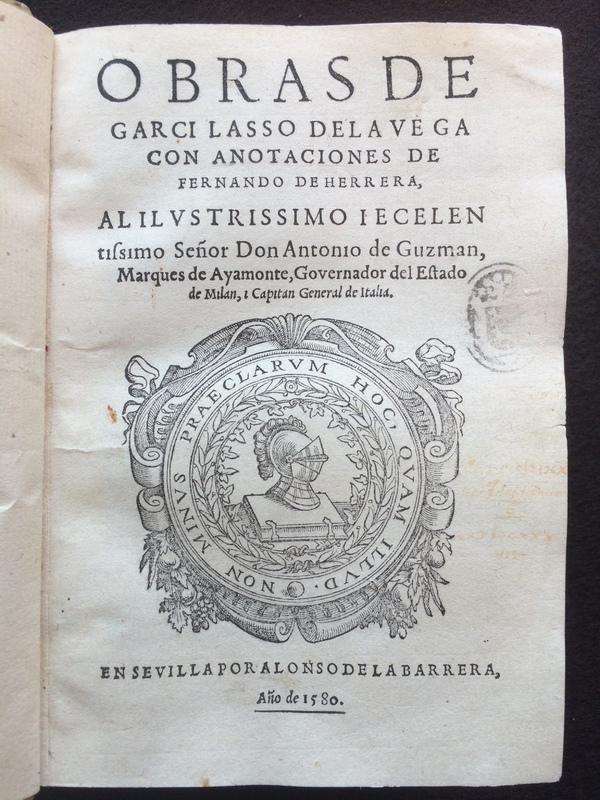

Marks from an Anxious Corrector: Fernando de Herrera

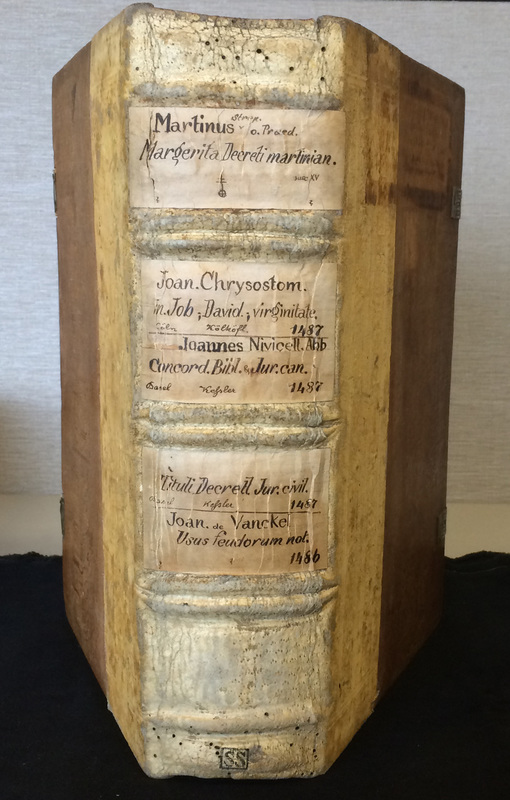

On the Footsteps of Owners: From Monastery to Monastery