The Picturesque

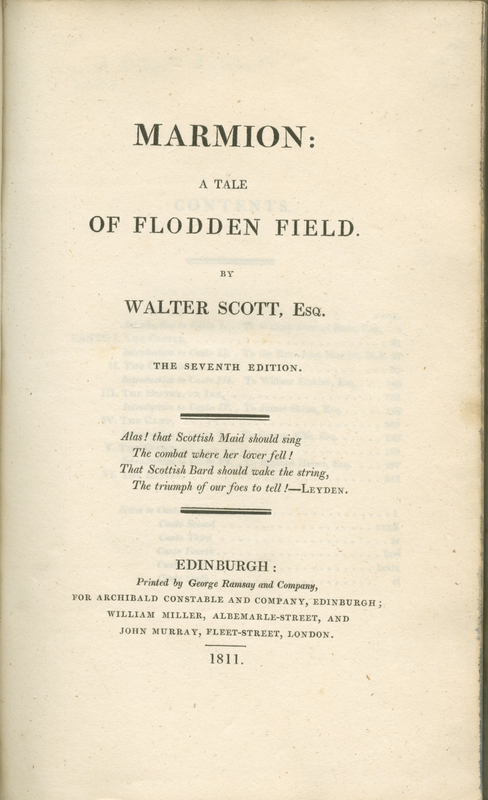

Marmion, a poem in six cantos by the phenomenally popular author Sir Walter Scott, is a historical romance of the sixteenth century that ends in the Battle of Flodden (1513), one of the worst defeats in Scottish history. For Scott, landscapes with connections to history embodied the highest form of the picturesque. More adept and interested in describing action than in delineating or painting scenery, Scott explains in his memoir that his talent as an artist lay less in portraying the picturesque in scenery than in peopling it with its history: “shew me an old castle or a field of battle, and I was at home at once, filled it with its combatants in their proper costume, and overwhelmed my hearers by the enthusiasm of my description.” Scott’s attention to action and to the people who propel that action is portrayed in the decorative cover for this edition of Marmion.

Austen expressed both admiration and a certain amount of jealousy toward Scott, threading references to him throughout her novels, as in Marianne’s enthusiasm and Anne Elliot’s shared admiration with Captain Benwick. In an 1814 letter to her niece Anna following the publication of Waverley, Austen half-jokingly complains that “Walter Scott has no business to write novels, especially good ones. —It is not fair. He has Fame and Profit enough as a poet, and should not be taking the bread out of other people’s mouths. I do not like him, & do not mean to like Waverley if I can help it—but fear I must.”

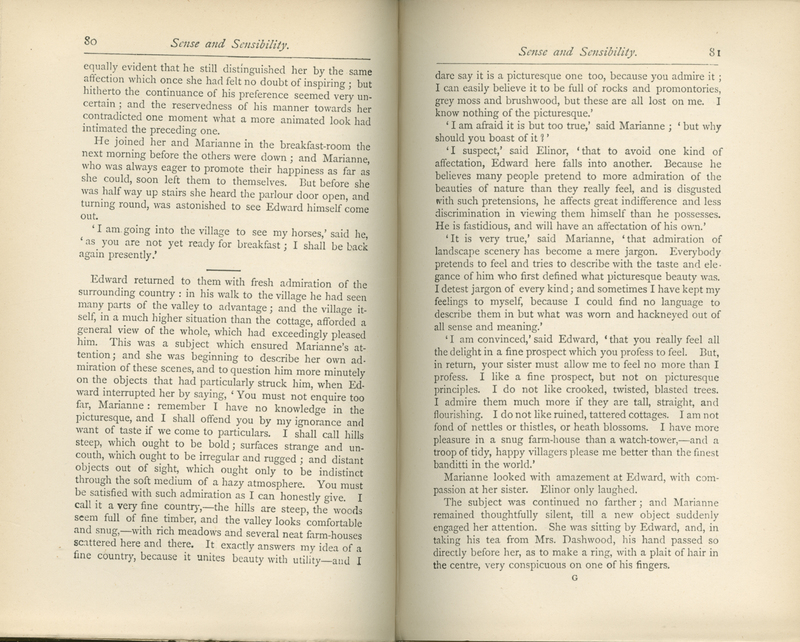

In this scene in Sense and Sensibility, Edward Ferrars and Marianne Dashwood present two different modes of admiring the countryside: Edward’s pragmatic view of the landscape which emphasizes the intersection of “beauty and utility” and Marianne’s admiration of the scene’s picturesque qualities. Their conversation in this scene underscores the extent to which notions of the picturesque, and, in particular, its specific language for admiring the “irregular” and “rugged,” had infiltrated popular discourse about scenery and landscape. Edward hopes to be allowed to admire the landscape on his own terms, whereas Marianne sees his inability to see its picturesque beauty as a character flaw that bodes ill for his relationship with Elinor.

Austen was well aware of these prevailing theories of the picturesque, particularly through William Gilpin’s foundational Three Essays: On Picturesque Beauty: On Picturesque Travel: and On Sketching Landscape (1792).

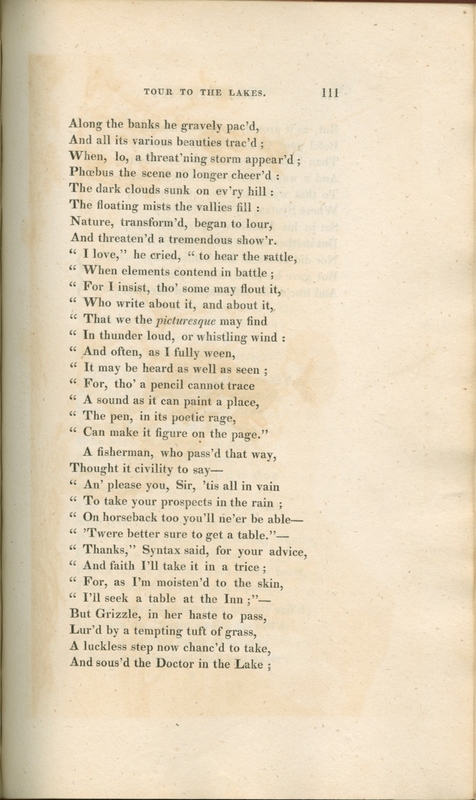

Originally published in Rudolph Ackermann’s Poetical Magazine between 1809-11, William Combe’s The Tour of Doctor Syntax: In Search of the Picturesque, illustrated by the caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson, is the first in a series of books satirizing the nineteenth century enthusiasm for the picturesque. Admirers of the picturesque celebrated landscapes characterized by roughness and irregularity, which the landscape gardener Uvedale Price defined as between the beautiful and the sublime, or awe-inspiring, in his Essays on the Picturesque (1810). Enthusiasm for the picturesque led writers and painters on tours to find picturesque landscapes worth painting and writing about.

Many readers have noted a connection between Elizabeth Bennet’s northern tour with her aunt and uncle and other travelers’ quest for the picturesque. When the tour is first suggested to Elizabeth, she responds with joy, exclaiming “what delight! What felicity! [….] What are men to rocks and mountains? Oh! What hours of transport we shall spend!” Elizabeth’s eagerness to see picturesque landscapes coincides with many of her contemporaries’ quests for similar natural scenes.

Landscape

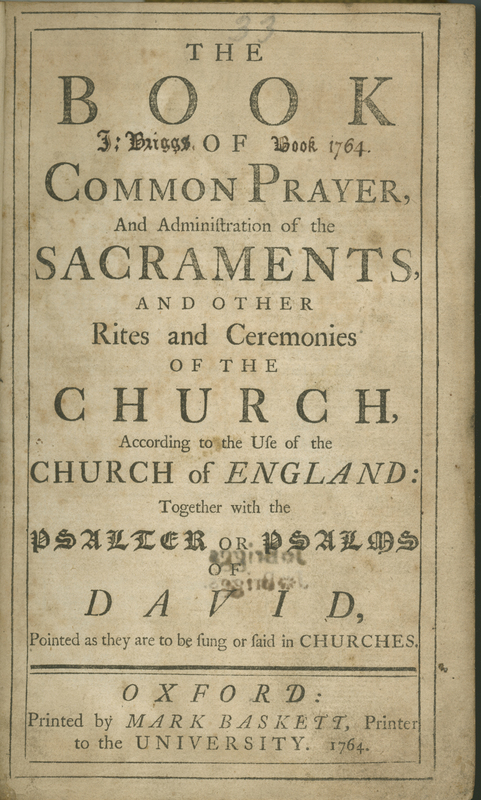

Religion