Education of Women

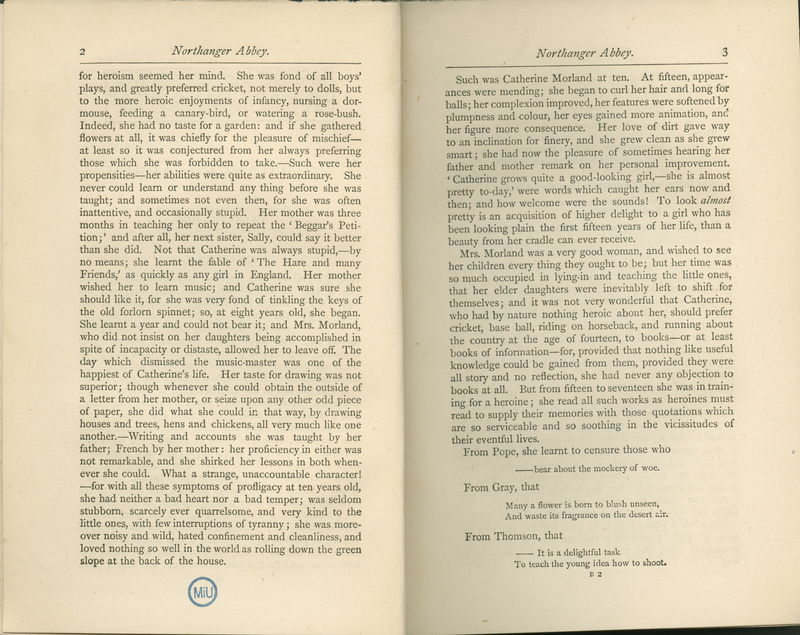

As the passage on display from Northanger Abbey alludes to, Georgian mothers commonly oversaw their children’s early education. In this context, it is important to note that eighteenth century commentators shared an understanding of education as not merely the acquisition of skills and accomplishments, but as the formation of moral beings and good citizens. Women’s responsibility and potential for authority in this area was widely recognized, granting them significant, if limited and contested, authority as mothers and teachers. The school room was not merely a place for learning arithmetic and embroidery, but for commenting on political and social issues.

While Jane Austen left behind few statements about education, critics such as Michael Giffin make a case that her six published novels all share a concern with education in the sense of moral development. Marianne’s educational epiphany is explicit in her dramatic realization of how her excesses of sensibility have caused suffering to her mother and sister. Through mis-steps in her Bath adventures, Catherine gains the experience needed to accurately “read” people and events. Elizabeth Bennet gradually subdues her own pride and acknowledges the prejudice that blinded her to Wickham’s wickedness. The self-education of the protagonists in Austen’s novels is worth recognizing in the context of broader eighteenth century debates on the nature and quality of women’s education.

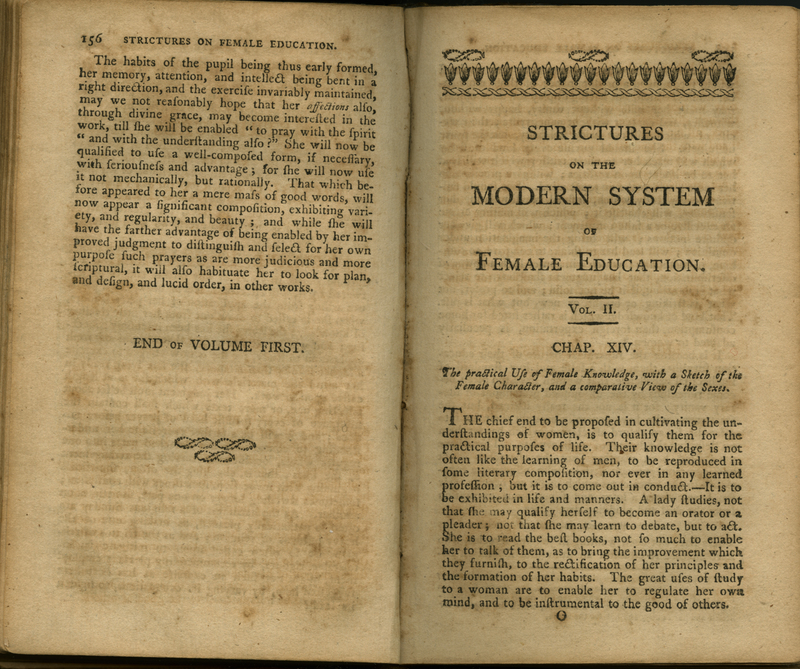

Known as a poet, playwright, and essayist, Hannah More’s defining concern was education as a path to a moral life. As young women, More and her sisters ran a boarding-school for girls in Bristol, and later in life they managed several charity Sunday schools for children of the poor in Mendip. First published in 1799, More’s Strictures on the Modern System of Female Education was immensely popular, with several editions published in that year alone. Writing from an Anglican evangelical standpoint, More decried both an excess of sensibility, but also what she saw as an overly aggressive approach by Mary Wollstonecraft. More believed strongly in hierarchical society, but felt that the upper ranks held a responsibility to be exemplary in self-improvement and manners. In Strictures…, More urged gentry women to abandon frivolous accomplishments and idle enjoyments (including the reading of recreational literature) in favor of a focus on religion and good works. While supporting a patriarchal state and family, and distinct provinces of life for men and women, More’s exhortations to serve and improve the poor justified female activism and participation in public life.

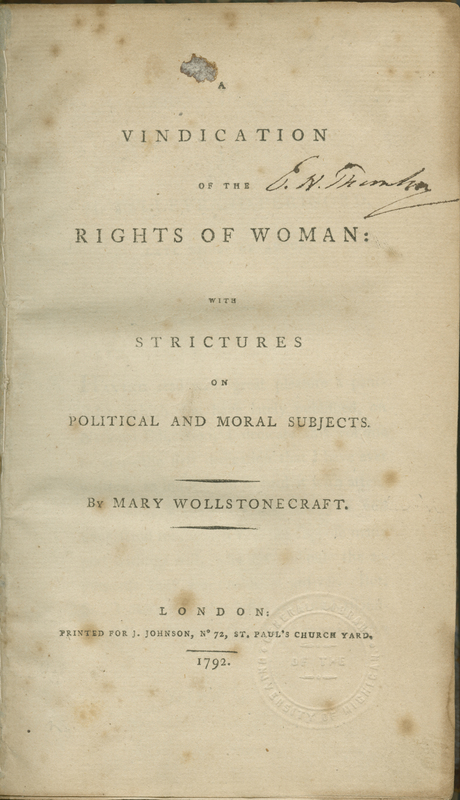

While Hannah More and Mary Wollstonecraft were political opposites, both agreed that women’s education should be substantive, not merely a collection of superficial accomplishments intended to attract a husband. While More focused on how the drive for frivolous accomplishments distracted women from their role as moral and social reformers in the home and community, Wollstonecraft argued that the focus on such ornamental skills prevented women from developing to their full individual and social potential as intellectually-independent and moral beings.

Wollstonecraft saw education as crucially tied to the fight for enfranchisement, the right to paid occupation, and the transformation of family relationships. In Vindication.., she presents two visions of womanhood: one shaped by the flaws of current female education—trained by habit to be physically weak, concerned only with domestic management and coquetry, and corrupted by her dependent situation; and another formed by serious and substantive education — physically and mentally strong, rational, trustworthy, and full of civic virtue.

Domestic Arts

Condition of Women