Domestic Arts

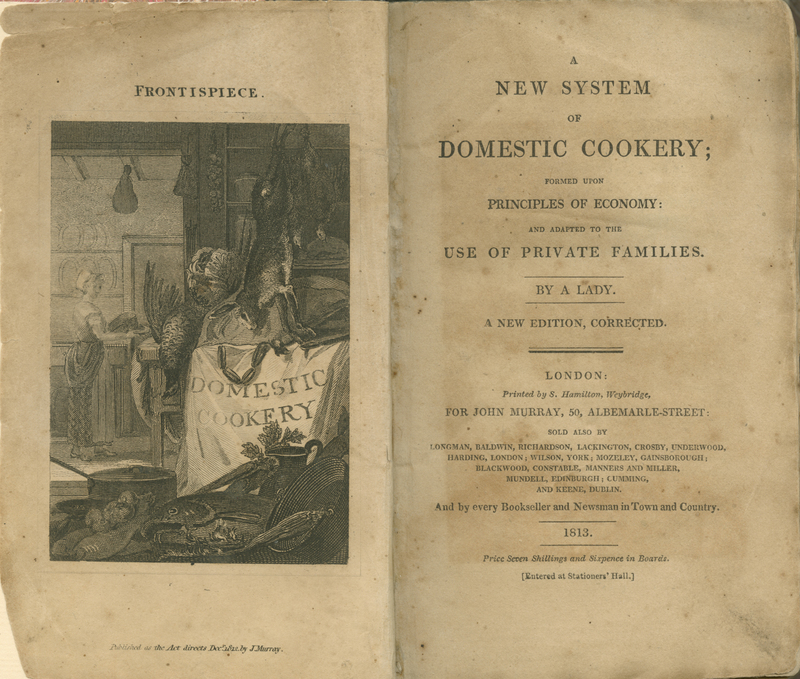

Maria Rundell’s collection of recipes and household tips was first published in 1806 by John Murray, who was also the publisher of Emma, Persuasion, Northanger Abbey, and the second edition of Mansfield Park. Rundell’s work was an immediate bestseller and continued to appear in new editions for decades.

Many of the dishes that appear in Austen’s works are represented in Rundell’s recipes: the white soup served at Mr. Bingley’s ball, Mr. Hurst’s favored ragout, Elizabeth Bennet’s preferred roast, and Mr. Woodhouse’s beloved gruel. It is unlikely that Emma Knightly or Elizabeth Darcy would find themselves in the kitchen, but each would certainly be involved in household budgeting and menu-planning. Humbler heroines destined for the parsonages of Mansfield and Delaford, on the other hand, while still assisted by servants, might well take a more hands-on role. At various times in her life, Jane Austen herself took over housekeeping responsibilities in the absence of her mother or sister. During her years at Chawton House, she held the particular responsibility of preparing toast and tea for breakfast in the parlor, while her mother, sister, and Martha Lloyd handled most other aspects of household management, leaving Jane more time for writing.

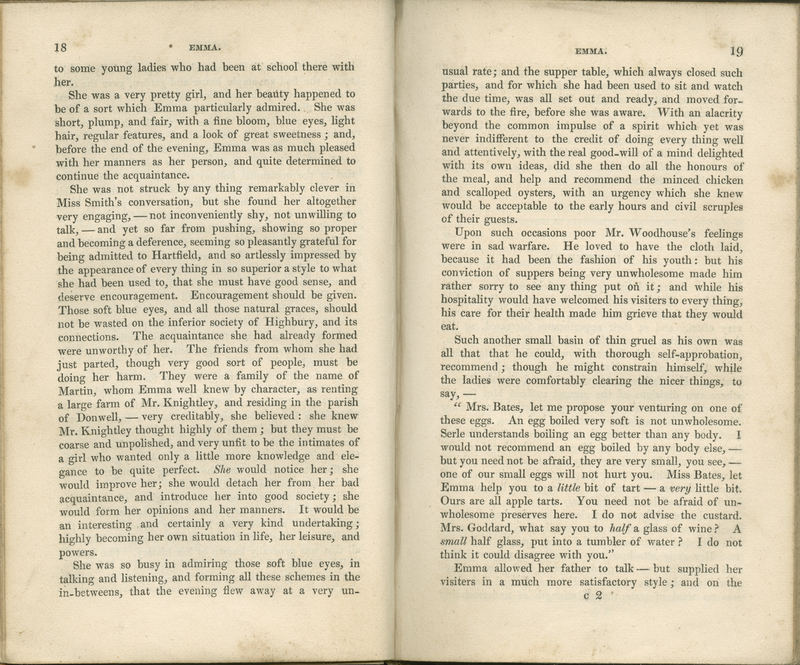

As a novelist, Jane Austen uses detailed description with a light hand. Emma is perhaps Austen’s most detailed novel, particularly with regard to food. From the Mr. Woodhouse’s assurances that “an egg boiled very soft is not unwholesome,” to the apples sent to the Bates household by Mr. Knightly and baked by the Wallises, the giving and receiving of foodstuffs feeds the network of obligation and gratitude connecting the community of Highbury.

Emma is conscious of her role as lady bountiful in this network, but throughout much of the novel, she acts in a secure belief of her own superiority and for “the credit of doing every thing well.” Her lack of true compassion is revealed at Box Hill, where she teases Miss Bates about the difficulty of saying only three dull things at once. Mr. Knightly takes Emma to task, reminding her that Miss Bates, “has sunk from the comforts she was born to; and, if she live to old age, must probably sink more.” In contemplating her treatment of Miss Bates, as in her ill-fated interference with Harriet Smith’s romance, Emma learns to accept the responsibilities as well as accolades that come with being a leading lady.

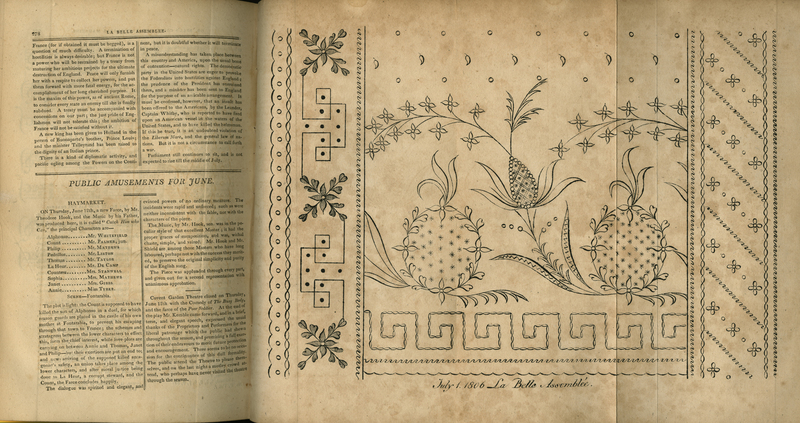

Published from 1806 to 1837, La Belle Assemblée offered its readers a mix of original poetry and fiction, articles on politics and science, reviews of contemporary books and theatrical performances, and articles on child rearing, cooking, and other domestic occupations. This textual content was accompanied by fashion plates and embroidery patterns, such as this pineapple pattern.

Embroidery and other forms of needlework were strongly associated with femininity in the Georgian period. During an evening at Netherfield, Mr. Bingley comments on how accomplished all his lady acquaintances are: “they all paint tables, cover screens and net purses. I scarcely know any one who cannot do all this.” Although Mr. Darcy demands a higher intellectual standard for accomplishment, and craftwork was sometimes criticized by Georgian commentators as nonproductive and frivolous, there was a strong current of public opinion valorizing decorative needlework. The Reverend James Fordyce (from whose sermons Mr. Collins reads to the Bennet sisters) praised women for decorating homes with their own handiwork, and author Maria Edgeworth recognized the value of craftwork in filling the solitary and sedentary hours that lay heavily on genteel women’s hands.

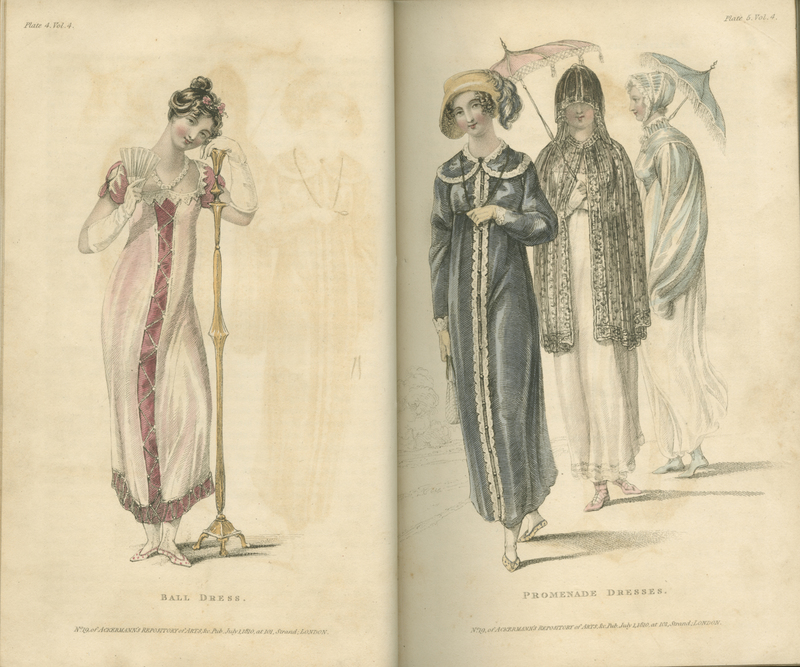

Dancing and Fashion

Education of Women