Condition of Women

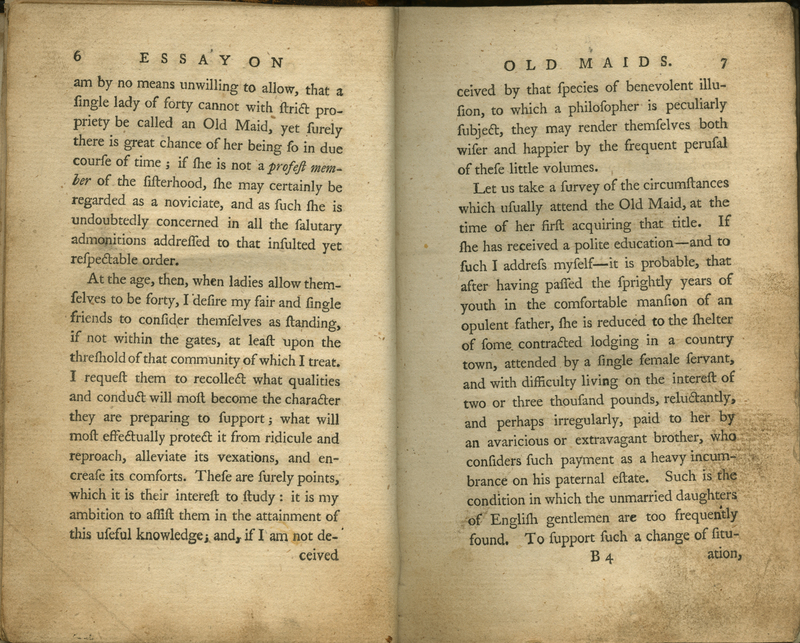

The poet and biographer William Hayley first published this essay on old maids anonymously in 1785. Reprinted multiple times in the early years after publication, the work was widely read and excerpted in periodicals. Hayley’s stated intention to defend old maids against critiques of their character and lack of sympathy for their situation underscores the prevailing hostility toward unmarried women in this period. While Hayley professes an earnest interest in the welfare of old maids, critic Devoney Looser argues that readers have long had difficulty determining whether this book is satirical or serious in tone.

Old maidenhood in this text is clearly laid out in class-based terms as a fall from comfortable middle-class life to a struggling existence. Hayley generalizes the condition of women who reach old maidenhood in the following way: “after having passed the sprightly years of youth in the comfortable mansion of an opulent father, she is reduced to the shelter of some contracted lodging in a country town, attended by a single female servant, and with difficulty living on the interest of two or three thousand pounds, reluctantly, and perhaps irregularly, paid to her by an avaricious or extravagant brother.”

Regardless of the facts of any individual unmarried woman’s situation, Hayley’s essay, and Austen’s portrayal of single women like Jane Fairfax and Charlotte Lucas, point to the vulnerability of those who lacked independent means and had few options for earning a living.

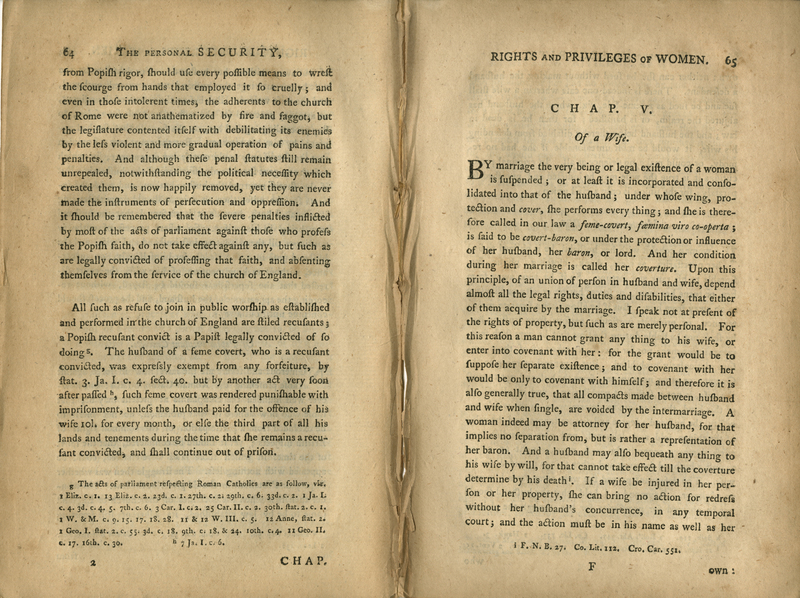

As pointed out in the legal discussion featured here, in Jane Austen’s time married women were subject to the common law custom of coverture, the legal subordination of women to their husbands, and thus enjoyed very few rights. In this legal framework, all of a woman’s property that she brought to a marriage or attained after marriage was controlled by her husband unless separate financial settlements had been made. As a result, married women could not own property, make contracts, sue or be sued, or have legal custody of their children. The vulnerability that married women experienced as a result of coverture was a target of feminist activism, but the law was not amended until the Married Women’s Property Acts of 1870 and 1882. Writing in 1882 of the act passed that year, the barrister William Andrews Holdsworth noted that it allowed women “to retain, acquire, hold and dispose of property in all respects as if she had still remained single….In future she may hold her own property not only against the world at large, but against her own husband.”

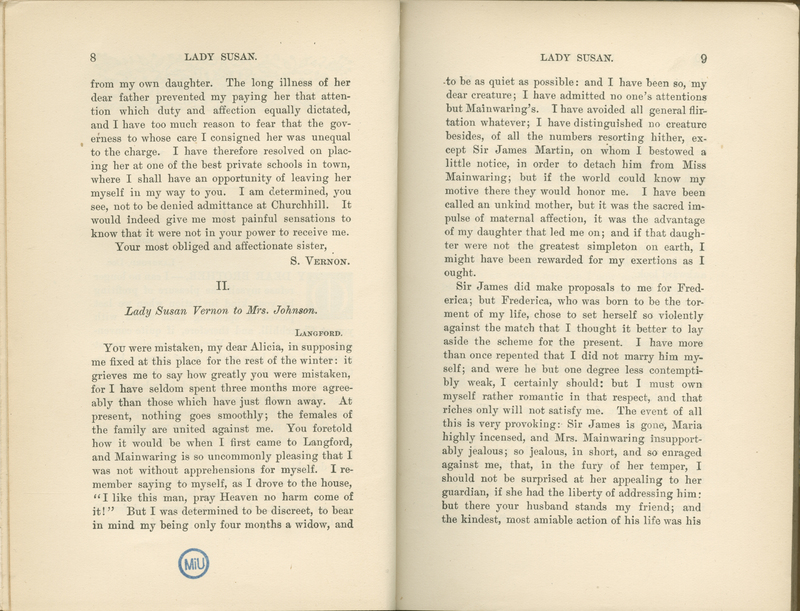

In the opening pages of Lady Susan, readers get a clear picture of two different sides to Lady Susan: the diplomatic supplicant hoping to maintain her brother’s good graces so that she can pay him an extended visit and the archly calculating Lady Susan who bemoans being expelled from a comfortable house where she could flirt with a handsome, if married, man. Lady Susan’s complex situation points to larger social issues. While she undeniably schemes both for her own advantage and that of her daughter’s, her efforts are directed toward finding a financially comfortable marriage for her daughter (who resists all of her mother’s efforts) and herself.

The brilliance of Austen’s epistolary novel is in the way that Lady Susan’s scheming makes explicit the strategies a woman—especially a widowed or single one without abundant economic resources—must undertake in order to secure a comfortable living for herself. Lady Susan is condemned for her maneuvers, as well as for her lack of affection for her daughter, whom she primarily sees as a means to achieving her ends. Although Lady Susan lacks the delicacy that is socially expected of her, she makes a home for herself in a situation where no one else would have made that possible for her.

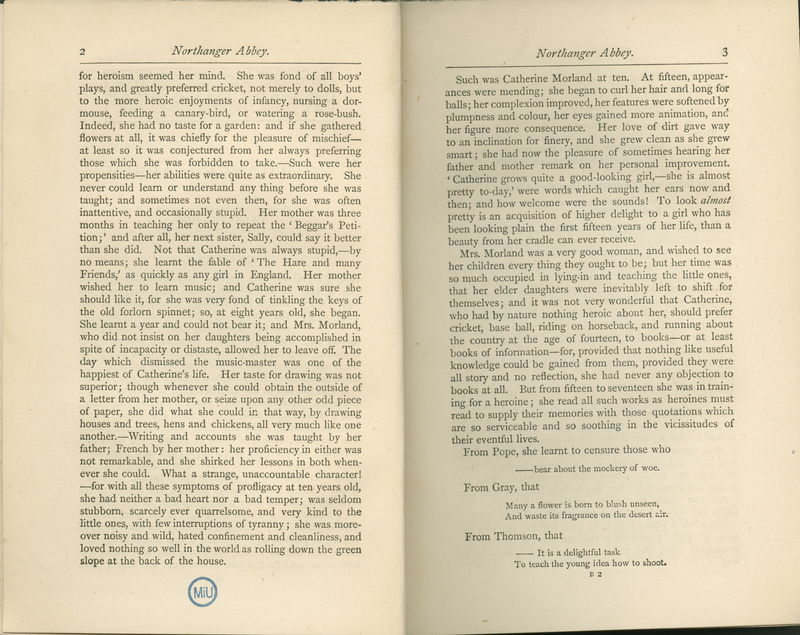

Education of Women

Landscape