Exploring Georgian England

Often celebrated for their timelessness, Austen’s novels were in fact highly responsive to current events and cultural trends. She was a voracious reader, well-versed in everything from the literary achievements of her predecessors and contemporaries, to politics, to fashion. Her novels reflect and comment on her era’s mores, practices, and places. In this section we highlight some texts and topics that are essential to understanding Austen’s place in her historical context.

Novels and Plays

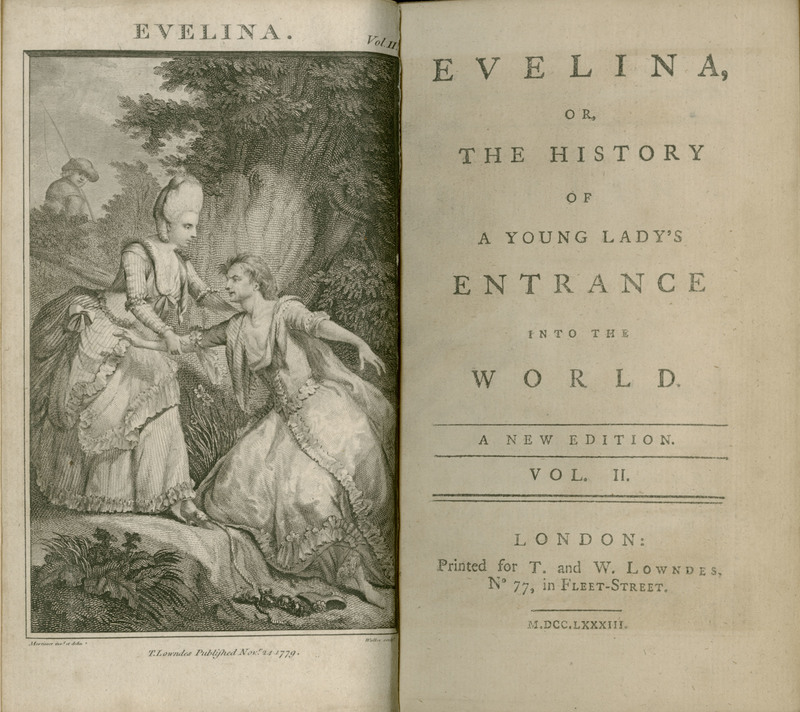

This three-volume epistolary novel explores the development of a young woman’s societal education in eighteenth-century England through the comedic use of embarrassment and social faux pas. Evelina explores many of the same subjects that Jane Austen later became famous for, though it precedes Austen's first published novel, Sense and Sensibility, by thirty-three years. Burney’s influence on Austen can be seen in the later novelist’s initial attraction to the epistolary method, observed in Austen’s early works, such as the Juvenilia, and in the rough drafts of her later novels.

The frontispiece of Volume II depicts the aftermath of Captain Mirvan and Sir Clement Willoughby’s cruel joke on Madame Duval, where a concerned Evelina aids a distressed and disheveled Madame Duval. It was designed by John Hamilton Mortimer, an eighteenth-century painter, who produced three images to accompany the fourth edition of Evelina. Mortimer completed the designs just before his death in 1779, and William Walker then produced the etchings as seen in the printed editions. Mortimer’s work was commissioned by Thomas Lowndes, a publisher who operated at No. 77 Fleet Street where the the fourth edition of Evelina was printed. Both Burney and Jane Austen had their work printed on Fleet Street, which was for centuries the center of British publishing industry.

(Carly Gross, Taylor Moses, Michaela Tanksley)

The Monk by M.G. Lewis was a popular gothic novel that anticipated future novels, including Austen’s Northanger Abbey. The gothic novel’s classic traits consist of distressed heroines, settings in medieval architecture and monasteries in distant lands, and sensational plots. These books were highly popular, and were regular staples of the lending libraries of Austen’s era. The Monk and other gothic novels’ unrealistic plot and characters were significant for Jane Austen’s development of a more realistic style. In Northanger Abbey she parodies gothic conventions. Her heroine, Catherine Morland, fuses her reality with that of the gothic. She naively aspires to be a gothic heroine, even though they often endured endless horrors and--like Agnes and Antonia from The Monk--met violent deaths. At the same time, Austen borrows some of the features of the gothic novel, setting her book in a former abbey.

(Alexis Low, Kaitlyn Mann)

Playwright Elizabeth Inchbald’s Lover’s Vows first made its debut in 1798 at the Covent Gardens of London’s Royal Opera house. It was adopted from German dramatist August von Kotzebue's Das Kind der Liebe, and published the same year it was performed. The work remains the only play used in an Austen novel: the young characters in Mansfield Park choose to stage the play at home.

Lover’s Vows would have been strange choice of play for a home staging in Austen’s time, especially when performed by the younger characters in Mansfield Park. It is a drama with occasional comedy; the story concerns a dead woman’s illegitimate son trying to make his way in upper-class society and the budding romance between a blossoming woman and a priest. The play was seen as scandalous, for not only did it focus on romantic scenes between unmarried couples, but it also suggested necessary social reforms along sexual, economic, and moral lines. Austen utilized this scandalous reputation to shed light on her characters.

The edition of Lover’s Vows before you may have been almost identical to the one Austen used as she read over the script in her writing of Mansfield Park. If you seek to put yourself in Austen’s shoes, then go no further and glimpse at the same script that she, or Mary Crawford, may have looked upon.

(Sarah Ovresat, Dylan Summers)

Education and Conduct

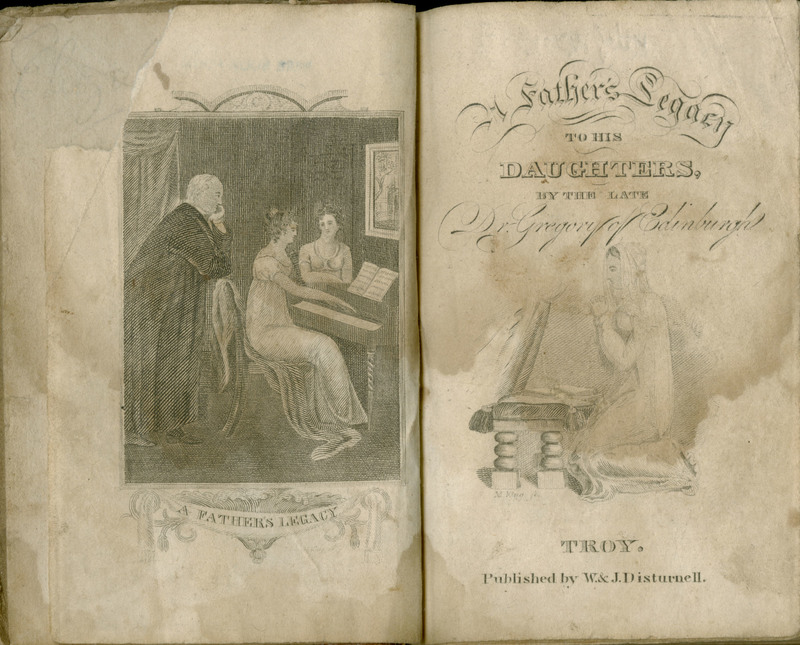

A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters is a conduct book written by Dr. John Gregory following the death of his wife in 1761. Not originally meant for publication, Gregory sought to record his wife’s opinion on young ladies’ conduct and intended the book to be presented to his daughters after his death. However, his son published the book in 1774 after Gregory’s death, and it was hugely successful. This popularity led to many editions and translations, including this particular edition from 1823. Gregory discusses religion, amusement, friendship, love and marriage, and, of course, his views on proper conduct. He asserts that women should be modest, delicate, cautious, and hide their wit. Overall, this conduct book represents eighteenth-century society’s cultural values and social pressures faced by women--ideas that Jane Austen incorporated into her novels.

A noticeable feature of this edition is its miniature size--referred to as “pocket-sized.” In the nineteenth century, printing costs were unavoidable pressures to publishers, especially due to a tax on paper in 1819. Consequently, publishers shrunk their book sizes so they could afford material costs. Minimizing the book size influenced the reading experience. By closely handling and reading the book, an intimate relationship was created between the reader and the text. Moreover, pocket-sized books made texts easily accessible--enabling on-demand access to literature that the reader thought was important, such as this conduct book.

(Victoria Bortfeld, Meryn Campbell, Elizabeth Wood)

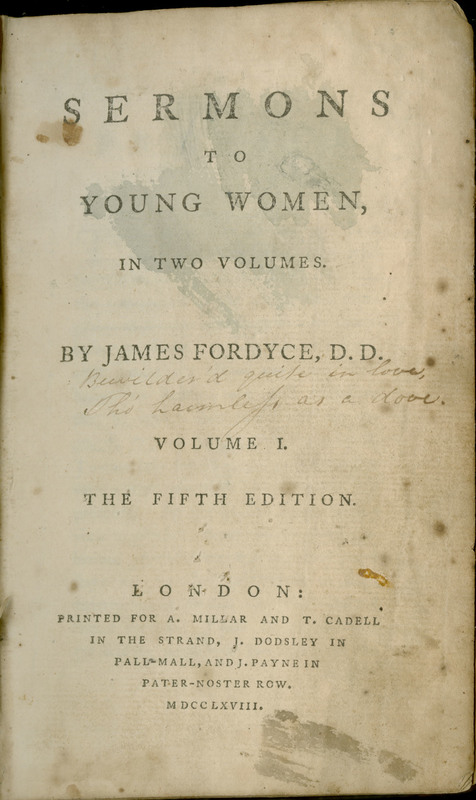

Initially conceived as a series of separate sermons preached to his congregation, Reverend James Fordyce's Sermons to Young Women, published in 1766, is a two-volume printed collection of the same sermons. As with other conduct books of the time, Sermons concerns itself with the definition and development of character, specifically—as the title clearly indicates—that of young women. With each chapter or sermon centralized around a specific topic, Fordyce ministers on such subjects as modesty, reserve, friendship, piety and meekness, as argued upon tenets of Christian doctrine. Sermons went on to see six editions in its first year of printing, making it an enormous success for the time. By the mid-1760s, Fordyce had become one of the most popular ministers in London. Less than a decade later, however, Fordyce's views on the role of women in society had begun to fall out of general favor; and by the end of the eighteenth century, such notions were considered as being nothing short of quaint. This decrease in popularity is evident in Jane Austen’s novels as she often alludes to conduct literature with a skeptical eye as many of her characters break these rules.

(Sarah Banister, Jesse Kim, Joshua Wirgau)

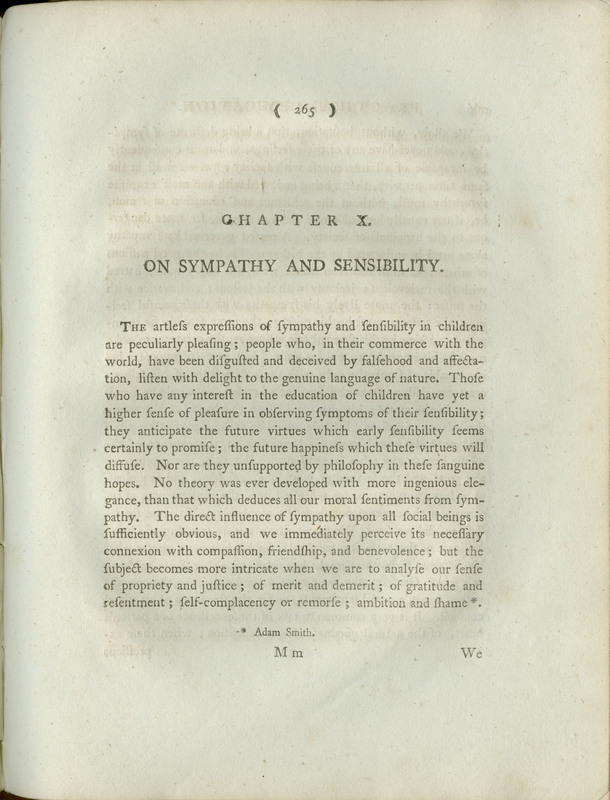

Maria Edgeworth was the author of many books that spanned multiple genres, published shortly before Jane Austen’s literary career. Edgeworth’s most famous novels include Belinda, Helen, and Castle Rackrent. Austen looked up to Edgeworth for her work on advancing the novel as a genre and referenced her in her own novels, such as Northanger Abbey. Practical Education was a joint project between Maria Edgeworth and her father, Richard Lovell Edgeworth. This unique conduct book included topics typical to the genre, such as how young ladies should conduct themselves, in addition to actual schooling techniques. While Maria wrote the chapters on subjects aimed towards young ladies, her father wrote the chapters concerning schooling lessons--and they were more often than not addressed specifically to boys. This reflects what we know of society at the time--Maria’s father had the knowledge to teach the more “scholarly” subjects to the boys, while Maria used her mother’s notes for the chapters related to more “feminine” topics.

(Miranda Hency, Alexandra Paradowski)

Hannah More’s Coelebs in Search of a Wife is a hybrid, both a novel and a conduct book that narrates the life of a young bachelor while simultaneously serving an instructional purpose. Given that the novel was not yet an established and respected mode of writing during More’s lifetime, as well as her dedication to spreading Evangelical moralist teachings, it is not surprising that Coelebs is the only novel she wrote. Despite it being her only novel, it was wildly successful, receiving praise from religious groups (which made up a large contingent of England’s early reading populace) that commended the novel’s advocacy of Christian values.The success of Coelebs played a pivotal role in elevating the novel’s status to a legitimate medium of high literature, setting the stage for Austen’s impending success. However, More prefered writing plays, poems, and essays, as is evident in her homage to John Milton; his verse not only appears on the front page of Coelebs, but is referenced throughout.

More’s writings were known to Austen and held a presence in her work, most notably in Austen’s Mansfield Park. More’s stylistic usage of satiric characterization and melodrama, and the themes of the ideal match and the importance of intellect and character in selecting a partner, were adapted by Austen.

(Anthony Okaneme, Sarah Shim)

Fashion and Design

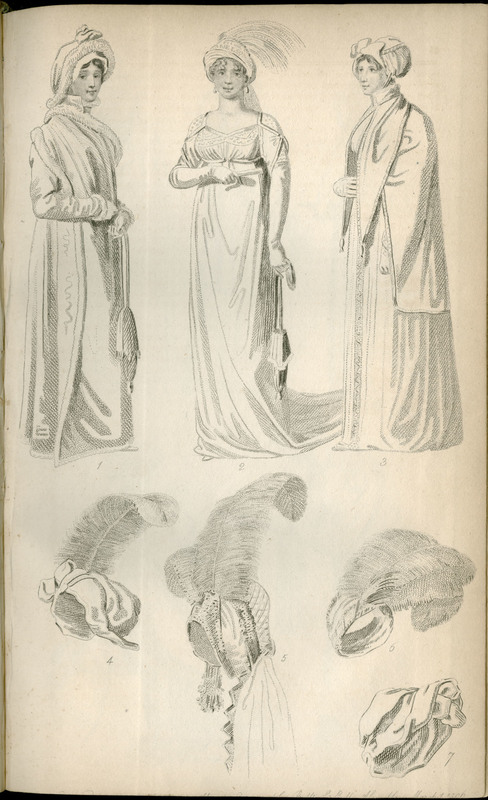

Though Savile Road was the one-stop shop for bespoke menswear tailoring, women were more involved in the process of making their fashion choices. They looked beyond London storefronts and into the pages of lifestyle magazines full of the latest poetry, social etiquette tips, art work, and of course, fashion. This is the first edition of La Belle Assemblée, a popular magazine amongst Regency era periodicals. The magazine, also known as Bell’s Court and Fashionable Magazine, was founded by John Bell and ran between 1806 and 1837.

La Belle Assemblée is known for being one of the first fashion and lifestyle magazines that catered specifically to women. The earliest issues, such as this one, included more than just fashion and touched on culturally significant items at the time such as poems and popular sheet music, though these were later phased out in the 1820s to favor more extensive coverage of fashion and profiles of prominent women of the time. La Belle Assemblée is remembered today for its fashion plates, of which there were two versions: the magazine was printed in black ink plates, though for an additional fee it could be purchased in a colored version as well.

(Caroline Filips, Emma Kinery)

Published in July of 1812, this volume of La Belle Assemblee circulated while Austen was editing Pride and Prejudice, which was published in early 1813. La Belle Assemblée comprises the latest fashions, biographies of “illustrious and distinguished ladies,” ornamental designs, descriptions and drawings of public assembly places, theater and novel critiques, and advertisements. The publication therefore functions as a guide for women from middle to high class social standings. It provides instructions on how to dress, where to go, and what popular opinions to have. Its content ultimately reflects a rise in consumer culture in early nineteenth century England, specifically targeting women through advertisement. Austen herself was enthusiastically interested in fashion. In a letter to her sister Cassandra, dated December 1798, she writes: “I have changed my mind, & changed the trimmings of my cap this morning… & I think it makes me look more like Lady Conygham now than it did before, which is all that one lives for now.” Here, Austen demonstrates a cultural trend leading women to imitate those of royal status in an effort to improve their own social standings. It is likely that Austen would have referenced La Belle Assemblée in her personal life: we know her niece Fanny Knight owned an 1814 issue. Austen may also have used this magazine, or a similar one, to imagine outfits for her characters and play on the social indications of their choice of fashion.

(Margaret Kolcon, Charlotte Merkle, Lara Moehlman)

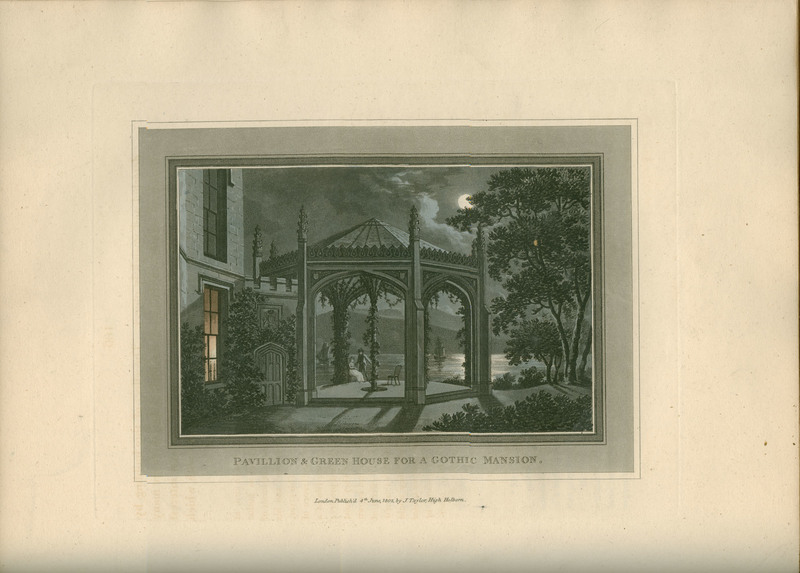

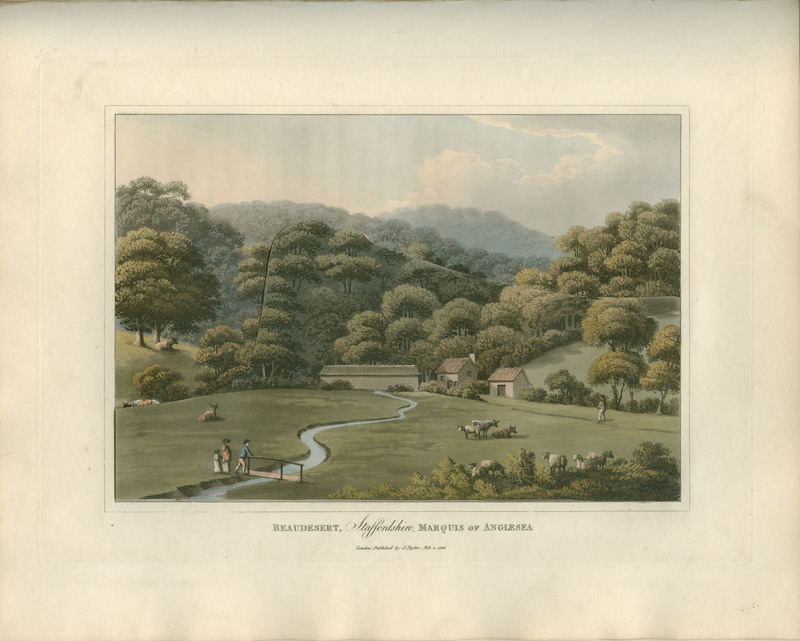

After training and failing in the textile industry, Humphry Repton (1752-1818) began his illustrious career as a landscape designer and architect. Repton's appearance was famously exhibitionist and landscape gardening offered him a chance to mix with the higher classes of society while making a living. Repton’s style relied on minimal changes, such as planting shrubbery or removing a wall, to achieve drastic aesthetic changes. He began to write about his projects in order to establish himself in his field. This coffee table book, published in 1802, is 16x10 inches with a cover of green stamped leather. It has large text and vibrant prints of before/after drawings of landscapes that Repton designed and executed. Alongside these drawings are descriptions of the project and any struggles that had to be worked through in order to complete the project.

Austen mentioned Repton five times in one chapter of Mansfield Park when Mr. Rushworth discusses remodeling Sotherton Court, making him the most mentioned factual person in any of Austen's novels. "Repton" had become a metonym, where his name was used as a generic substitute for every landscape designer and Austen's use of Repton's name was a satirical nod to popular culture. Repton’s book is also exemplary of the Gothic resurgence in architecture that inspired authors to write gothic novels that Jane Austen then parodied with Northanger Abbey. Observations is a testament to Repton’s influence throughout society during Austen’s time.

(Abraham Lofy, Olivia Velarde)

Humphrey Repton

Fragments on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening: Including Some Remarks on Grecian and Gothic Architecture...

London : Printed by T. Bensley and Son, Bolt Court, Fleet Street; for J. Taylor, at the Architectural Library, High Holborn, 1816

In late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century England, much attention was paid to an estate’s surrounding flora and fauna. This book by Humphry Repton, a renowned landscape architect of Jane Austen’s day, sets forth the renovations of wealthy estates in England, and the theory behind their designs. Repton, who coined the term landscape gardening, had a rapid rise to fame at the turn of the 19th century, in part because of the success of his books. These books, along with numerous commentaries over the importance of taste in regards to architecture and landscape design, display many watercolor illustrations of estates before and after his renovations.

In chapter six of Mansfield Park, in which Mr. Rushworth worries about who could renovate the Sotherton estate, Mrs. Bertram states that “Your best friend upon such occasion would be Mr. Repton, I imagine” (42). Many of Repton’s renovations involve an increase in the size of the house, an addition of ample gardens and bodies of water, and the removal of large trees. Most importantly, in regards to Jane Austen’s novels, Repton’s work paid attention to the dynamic relationship between an estate’s landscape and the humans that inhabit that landscape. Many of the spaces he created were conducive to social interaction, such as libraries, dining areas, gardens, and terraces, which Jane Austen often employed in setting the scenes of her novels.

(Shane Achenbach, Claire Tobin)

Food and Drink

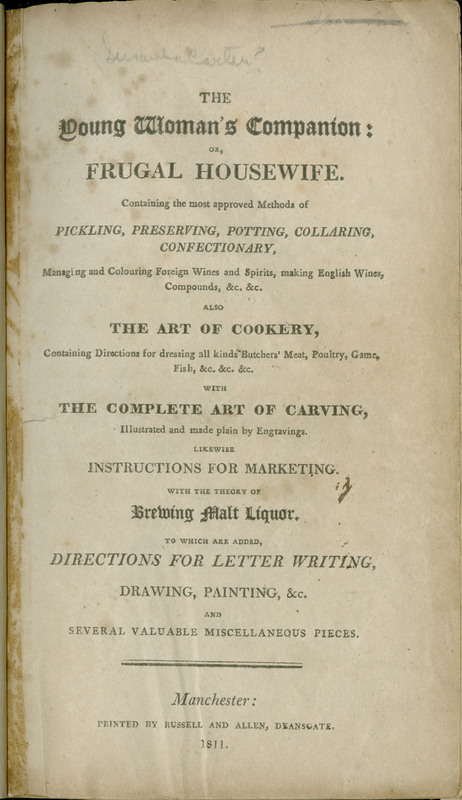

What today might be called “household management” was, in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, called “domestic economy” and referred to the connected relationship between the woman as a consumer and a homemaker. Many women in the nineteenth century were taught to chase an ideal of the “economic woman.” She was supposed to be the managerial figurehead of the household, maintaining the wellbeing of its structure and inhabitants with frugalness and efficiency.

The Young Woman’s Companion: The Frugal Housewife... is an example of the synthesis of the conduct book and the cookery book. Published in 1811, as the novel was beginning to replace the conduct book in popularity, this book can be seen as an attempt to revive the genre. With everything from pickle recipes to letter-writing tutorials, the book spans the two genres to create a guide marketed to the “economic” elite woman, with elements of a cookery book.

In the majority of Jane Austen’s novels, she structures characters’ introductions around their economic status. The young women in her novels, as a product of their class and era, were constantly navigating through the ‘marriage market’ and searching for a suitable, well-off husband. Instead of supporting the economy in the way we understand it today, Austen’s female characters served as a direct link between consumerism, marriage, and household management. For example, Mrs. Allen in Northanger Abbey pays intense attention to the cost of her outward appearance through the quality of the fabric of her clothes.

(Madeleine Gaudin, Dominic Polsinelli, Stephanie Stoneback)

Elizabeth Raffald

The Experienced English Housekeeper: For the Use and Ease of Ladies, Housekeepers, Cooks, &c., Written Purely From Practice

London: Printed for J. Brambles, A. Meggitt, and J. Waters, by H. Mozley, Gainsborough, 1808

A new edition

Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive

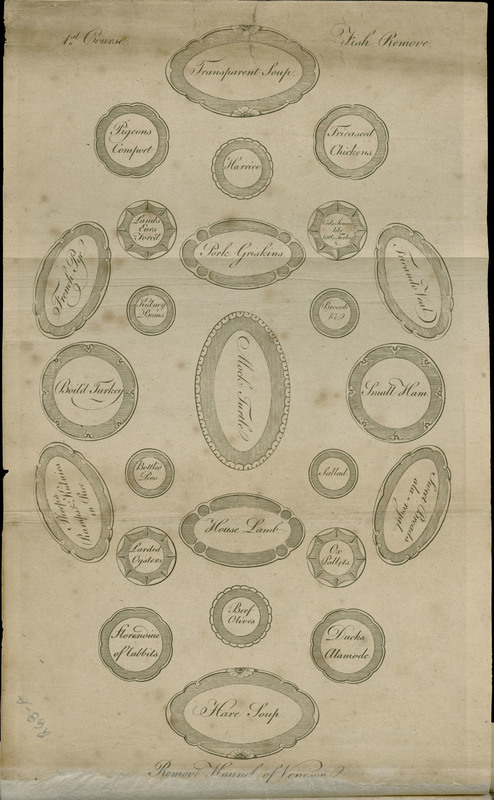

In upper class households, the dinner party was an elaborate production, often consisting of at least ten courses, each with a variety of dishes. Turkey, venison, duck, pheasant, and fish could all be served over the course of one meal along with various fruits and puddings. The most social meals could last three to four hours. Guests of the highest social standing were commonly seated next to each other around the table. These gatherings are common in Austen’s novels, and reflected the status of both those serving and those being served. The image of the table setting helps a modern-day reader understand the magnitude of executing such a dinner party.

Elizabeth Raffald’s instruction manual for housekeepers was initially published in 1769, and enjoyed large popularity in her lifetime. Male cooks were preferred by wealthy households, or at least a woman cook who had been trained beneath a man, so Raffald’s level of training and ability to pass on knowledge is unique in her time. Up until the book’s publishing, many cookbooks published had been written by men, so Raffald’s practical guide by a housekeeper for housekeepers filled a need. She had served in country houses as a housekeeper for fifteen years and her cookbook contains over eight hundred of her own recipes. The book also includes instructions for serving and setting the table, and even a drawing of the stove. Raffald’s inclusion of a diagram of the table is typical of cookery books of the period.

(Emily Fishman, Ingrid Johnson, Lars Johnson)

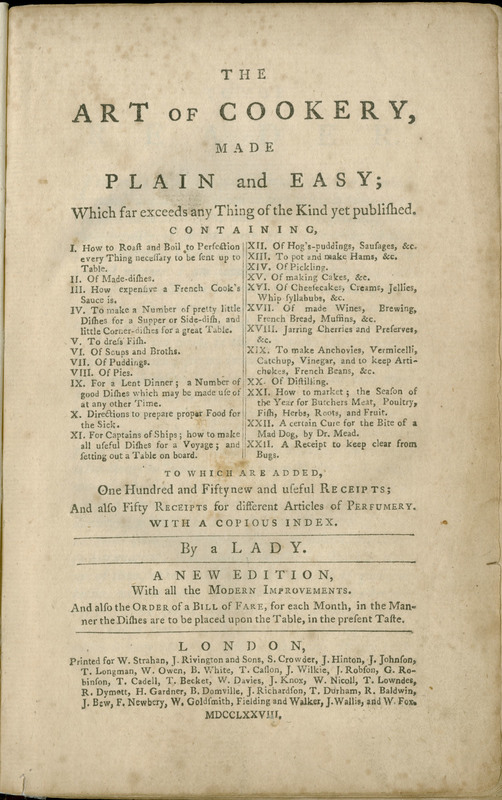

Toward the beginning of the nineteenth century, dining played a large role in the forming and maintaining of social acquaintances. Throughout many of Jane Austen’s novels, groups of individuals connect around a single circular table to engage in conversation, thus exchanging many niceties over food. Instructional books such as Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery... became immensely popular in the preparation of these meals. Although Glasse directs her work at servants in the introduction, middle class families often played an active role in the direction of these recipes. Even though Austen may not have been in the kitchen herself, her interest in exchanging these recipes and cooking tips has been documented in her letters to friend and companion, Martha Lloyd.

Dining in Jane Austen’s novels also held particular importance for her characters, as did simple conversation about food. At various times in Emma, Glasse’s recipes make a featured role in dinner scenes and conversation. “To make different sorts of tarts,” “to bake apples whole,” “to fry eggs,” and “to boil eggs” are all recipes featured in Glasse’s book, and are all foods which hold particular importance in exchanges between the characters in Emma. Baked apples are served to guests, and meals vary from gruel to those of scalloped oysters and chicken. The way a servant cooks eggs and a tart is held as a point of pride during dinner parties and a point of conversation for Mr. Woodhouse, demonstrating the gentry’s close association with the preparation of food

(Amber Mitchell, Natalie Zak)

Army and Navy

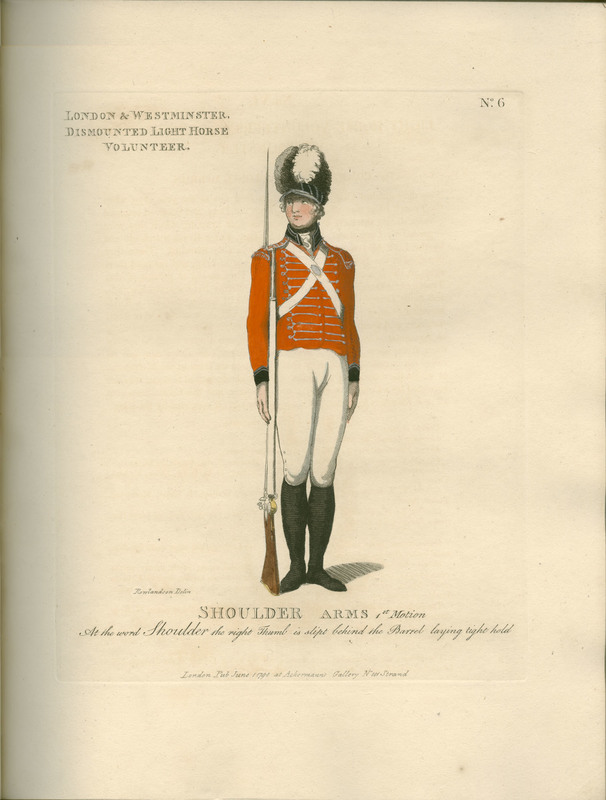

In the early nineteenth century, military pride and nationalism spread beyond matters of national security and into the realm of social dynamics and culture. Society’s perception of the military is explored in many of Austen’s novels, notably Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, and Persuasion. Numerous characters in her novels, including William Price, Colonel Brandon, and George Wickham have earned and elevated their social status through military efforts, showing an alliance between platoon and prestige. Furthermore, as we can see from the infatuations of Lydia and Kitty Bennet in Pride and Prejudice, military status was considered a desirable quality in a husband, suggesting bravery, patriotism, and masculinity. Many of the uniforms depicted throughout Loyal Volunteers of London bear similarities to the dress of military personnel that Austen depicts in her novels.

Published in 1798, Thomas Rowlandson’s work is comprised of proud illustrations of English military soldiers in their uniforms, accompanied by a description of their positions. As noted in the preface, and in the precise, elegant artwork in the text, this book was designed to elevate military pride and national zealotry, as well as to explain uniform particularities. For example, the uniforms of the London and Westminster volunteers are identical to the redcoat uniform of the British Army worn by George Wickham in Pride and Prejudice.

(Nicole Brindijonc, Ella Bruining)

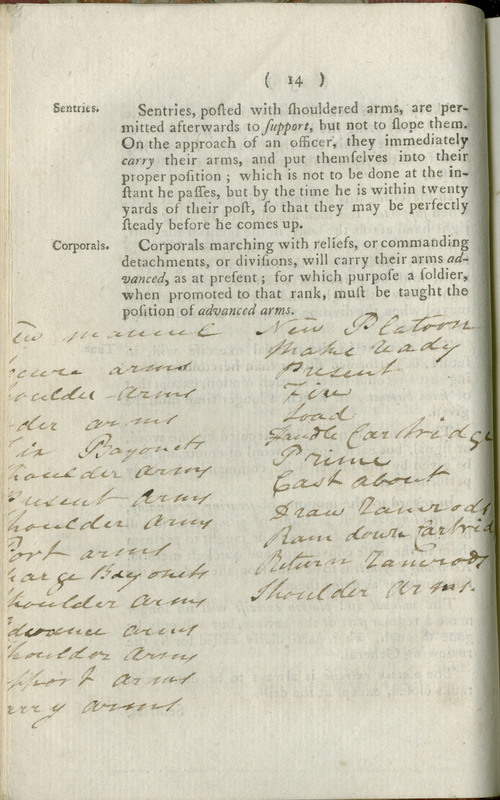

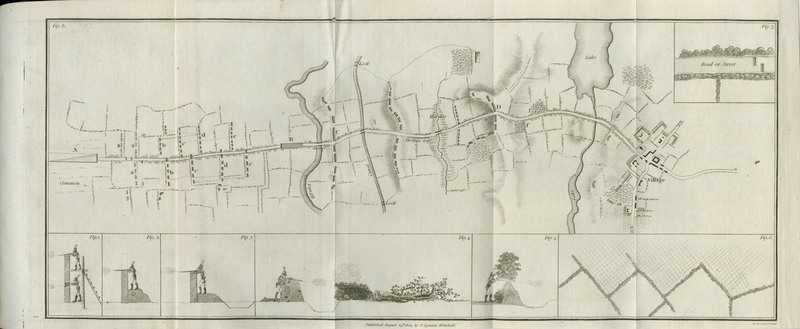

A Manual for Volunteer Corps of Infantry is a military guidebook. It was created by the British government in 1803 to help new soldiers navigate military life. For instance, there is a list of commands that the soldiers needed to know. Also, there are many foldout images that demonstrate how the soldiers should act in different scenarios. The book is written in brief, efficient military jargon, suggesting that people outside of the military probably wouldn’t have read it. The copy we have here most likely belonged to a soldier because it contains handwritten notes. Interestingly, T. Egerton (the publisher of this book) also published Jane Austen’s novels Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, and Mansfield Park.

Austen had two brothers, Frank and Charles, who were sailors in the British Navy. They brought knowledge of the war and navy into her life, which also went on to influence her writing. Furthermore, Austen also read military material, as she mentioned having read essays on military policy to her sister in a letter. While she could not have fought in the war, it is clear that she was very interested in the military and sought to learn how it worked. Military manuals just like this one were likely commonplace on the bookshelves of the Austen home. Regardless of her awareness of this book, war was heavily influential on her life and work and manuals such as this one were important at the time.

(Gilad Granot, Kimberly Sorenson)

The Martial Achievements of Great Britain and Her Allies; from 1799 to 1815 provides illustrations and narrations of the naval achievements of Great Britain. Interestingly, the folio lists 1814 as its publication date, but it contains multiple depictions of The Battle of Waterloo, which would not occur until 1815. Three additional drawings were then added to encapsulate the influence of Waterloo – even though the printing of The Martial Achievements had already begun.

During the period covered in The Martial Achievements, Jane Austen was writing her celebrated novels. Austen was heavily influenced by the Napoleonic Wars. Austen’s personal connection can be clearly seen through the preserved correspondence with her brothers. Francis and Charles Austen were sailors, who travelled to the Mediterranean, Adriatic, and Indian Oceans, among other waters. Austen sent her brothers her writing as a means to connect them to England, to home. Henry, her favorite brother, even served as her “literary advisor” from his overseas military post. Not only was Austen guided by her brothers, but her works were also inspired by her brothers’ roles in the armed forces. For example, the novels Persuasion and Mansfield Park track social changes in early nineteenth century England by illustrating the elevated status of sailors and the impending bankruptcy of the traditional ruling class.

In this way, Austen’s novels offer an alternative view of war. She redefines battle in terms of economic and social status, rather than dwelling on the traditional militaristic definition proposed by The Martial Achievements.

(Jenna Barlage, Claire Fairbanks, Ina Zaimi)

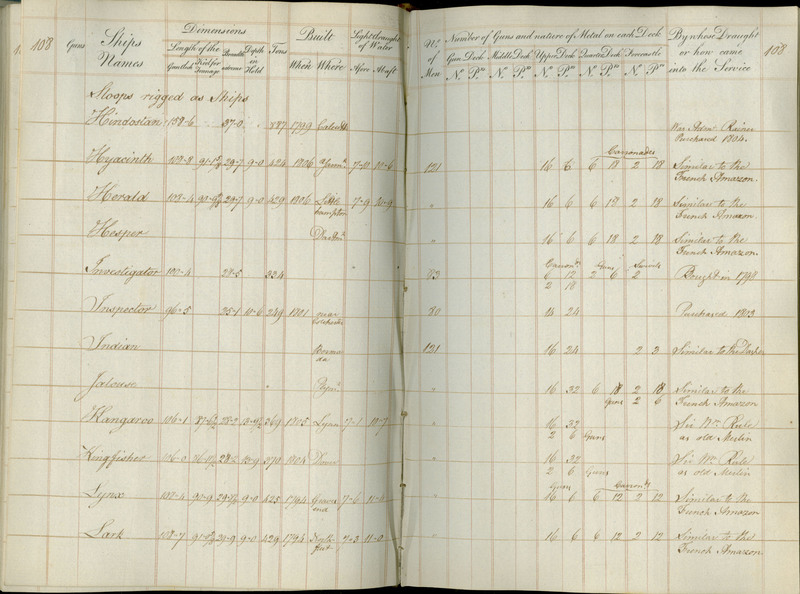

The British Empire, one of history’s most powerful and influential, was known for their variety of assets and tools that allowed them to remain in power for so long. One of those tools was the British Navy, which helped to create colonies and territories in locations such as Africa, India, and Canada. During Austen’s lifetime, Britain experienced a lot of change, losing a war to what would become known as the United States, when their navy was out-strategized, but also defeating Napoleon Bonaparte and France. While Austen does reference the navy throughout some of her novels, she often chooses to focus on relationships and create a world of her own, rather than writing in detail about current naval affairs. Interestingly enough, the mystery of Jane Austen’s exclusion of world events doesn’t compare to the mystery of this list of Royal Navy ships, which has no known author or publisher. Many portions of the book appear to be unfinished, with entire sections left blank. All that can be said for certain is that the ship information included on the list is accurate, and that these ships were involved in many military expeditions. A simple search across the web reveals that many of the ships included in the book were participants in some of Britain’s toughest battles. Perhaps, however, this list resembles the “navy-list” that Austen’s most famous sailor, Captain Wentworth, looks over with his friends in Persuasion

(Antonio Whitfield)

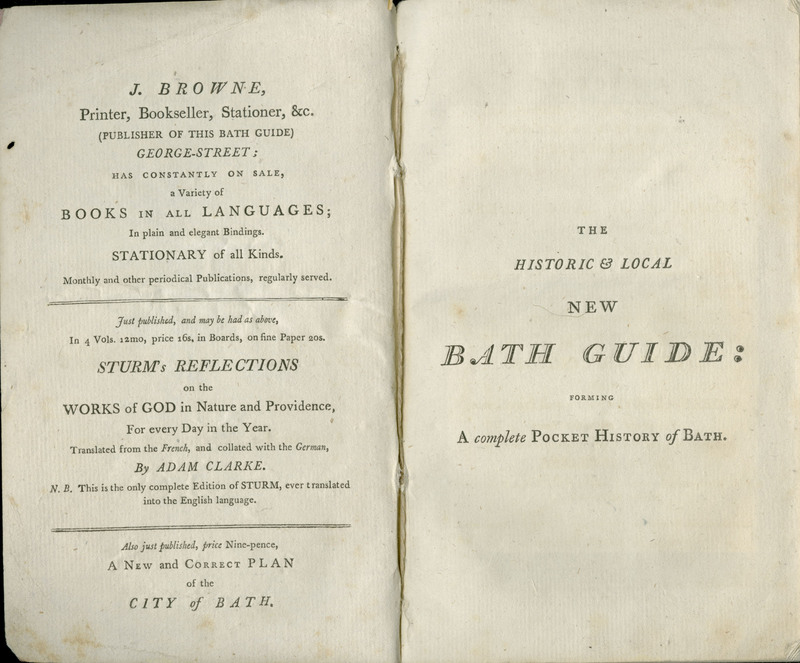

Bath

The Historic and Local New Bath Guide: Informing and Useful to Travelers, and those who visit and reside in this ancient city is a compact volume, small enough to be carried around the city with its owner potentially. Bath was a popular vacation spot during the end of the eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, known for its curative water. Bath was also seen as a prominent social scene. Public assemblies were the highlight of Bath socializing, with activities like dancing and chatting. Jane Austen’s first trip to Bath in 1797 was to visit her aunt and uncle, the Leigh‐Perrots. Jane loathed her first time in Bath as she thought the town was dirty and the weather was awful. A few years later she returned with her brother Edward and decided it really was quite tolerable. Jane Austen and her family later lived there from 1801 to 1806, perhaps using a similar guide to acquaint themselves with their new home. An anecdote notes that she fainted when she discovered that the family was going to move to Bath. Austen’s family lived near Sydney Gardens at No. 4 Sydney Place. Austen frequently spent her mornings at the public breakfasts in Sydney Gardens and enjoyed roaming around the Pump Room in her best dress.

(Julia Grant, Brooke Pennell)

John Claude Nattes captures the essence of picturesque city life in a selection of topographical paintings entitled Bath: Illustrated by a Series of Views. The collection depicts several landmarks that Jane Austen herself visited and wrote about. As scholar Jean Freeman highlights, “No admirer of Jane Austen and her works should be without some knowledge of the city of Bath and of the considerable part it played in her life.” Referenced in all of her novels, and the central setting of two, Bath indubitably influenced Austen’s life and work.

The city of Bath was named after its hot springs and became famous for its pump rooms. In these rooms, British elite would gather to socialize and drink the water, which was believed to have restorative properties. Jane Austen includes several descriptions of pump rooms in both Northanger Abbey and Persuasion. However, while the city is portrayed favorably in the former, the city’s description becomes decisively more negative in the latter, written thirteen years later. This shift in attitude reflects events in Jane Austen’s personal life that soured her perception of the city and influenced her attitude toward it in her writing.

(Emma Furlong, Trevor de Sibour)

Spotlight on Austen's Novels

Fans & Readers