The Growth of Fashion Publishing, 1785–1815

Much like today’s fashion magazines, early fashion journals promised to provide both women and men with “exact and prompt knowledge” of new fashions and accessories in clothing and home furnishings. Editors repeatedly assured readers that a journal’s fashion plates represented real clothing observed in the city or even in the homes of stylish people. To further shore up the perceived cultural value of their publications, most fashion journals included content that went beyond fashion, covering topics such as literature, fine art, and music. Fashion journalism also became international during this period, though London and Paris were the primary trend-setting centers of fashion. Even during the twenty-plus years of political and social upheaval that engulfed Europe as a result of the French Revolution (1789-99) and the subsequent Napoleonic Wars (1803-15), fashion plates continued to circulate throughout Europe and the Americas, where they were integrated into local fashion journals. These Fashion journals and the images they commissioned played a crucial role in securing the definition of “fashion” as a fast-moving, cosmopolitan phenomenon distinctly different from traditional “costume.” Journals also reinforced Europeans’ notions of cultural superiority: in the words of a 1785 Cabinet des Modes editorial, fashion seemed to offer a visual signifier of the differences between “happy and well-governed nations” and “savage” ones.

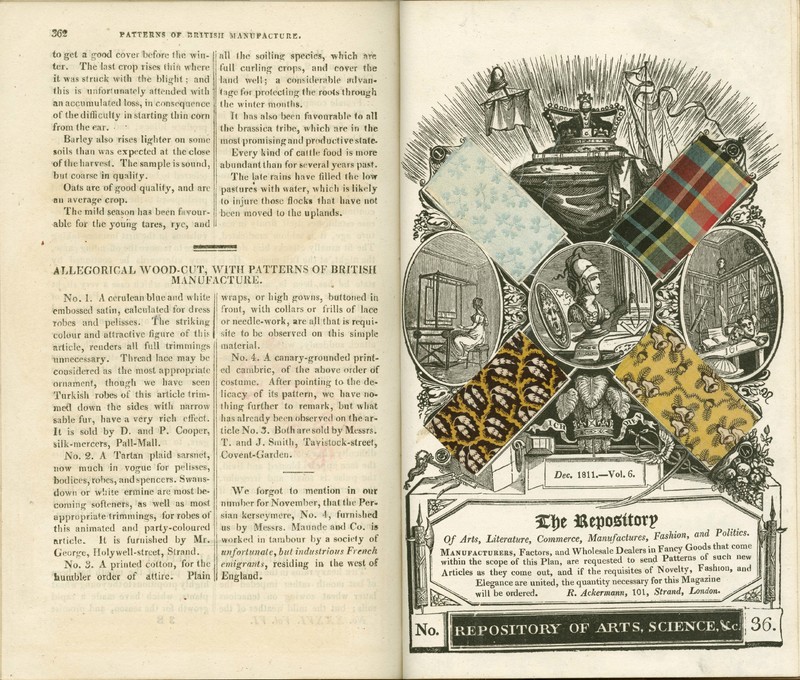

Fashion journals were as much a commodity as the clothing they documented. As the objects depicted here show, images of fashionable dress were available in a range of formats, from tiny books that could be used “on the go,” to large prints more suited to being examined at home or in a print shop window. In this period the journals’ hand-colored engravings would have been produced separately from the text. Once a subscriber had collected a year or two’s worth of issues, he or she would typically have them bound. [CW]

This fashion plate appeared only a few months after the French Revolution broke out in Paris in 1789. Fashion is a phenomenon that feeds on constant change, but the “disastrous catastrophes” associated with the Revolution (as this bi-monthly Paris-based fashion journal’s editor termed them) temporarily brought new fashions to a standstill. By November, the editor reported that although silhouettes remained stagnant, a growing number of symbols of democratic political solidarity were being integrated into existing styles. In this image, the top left shoe buckle takes the shape of the notorious Bastille prison, while the featured fabric for women’s dresses drew inspiration from the striped tri-color ribbons men had begun tucking into their buttonholes and affixing to their hats. A buckle pictured in the next issue was even more explicit in spelling out its politics: the phrase “Vive la Nation” (a pointed rebuff to the previous mantra “Long Live the King”) was formed from metallic letters. The related commentary observed, somewhat wistfully, that such buckles were no longer made of glistening silver but instead of humble copper, in a nod to the Revolution’s promotion of democracy. Luxurious materials crept steadily back into fashionable clothing, however, as the egalitarian fervor that had initially powered the Revolution waned. [CW]

Sitting by a dock and apparently unconcerned with sullying her pristine white dress, the woman in this plate reads contentedly. Behind her, ships with waving “Union Jack” flags pointedly situate the scene not in Paris, long the capital of fashion, but in London.

Britain had declared war on France following the execution of the King Louis XVI in January 1793. The journal’s editor, Nikolaus Heideloff (1761-1837), used the period’s intense geopolitical tensions to promote a distinctly British fashion press, as the preface to the first issue (April 1794) made clear: “This work, so necessary to point out the superior elegance of the English taste, is the first and only one ever published in this country; it surpasses any thing of the kind formerly published in Paris . . ..” The larger scale, highly detailed graphic style, and distinctly English setting of this fashion plate demonstrate these ambitions visually. Heideloff had even larger ambitions for the impact his journal would make; he predicted that its fashion plates would, “become even more interesting at a remote period.” This statement implies that these paper images were not ephemeral trivialities, but rather engaging works of art and important documents for reflecting on cultural history. This exhibition demonstrates the prescience of Heideloff’s comment. [CW]

In this tiny fashion plate less than 6 inches tall, a richly-attired woman appears to twist backward against the white void of the page. The twisting pose shows off several sides of her garment, while also directing the reader’s attention to the book’s title. The following page offers detailed textual information about the image, describing the twisting woman’s hat as a “helmet” (casque) topped with ostrich feathers, her red robe as velvet edged with swan’s down, and her shawl as made of lightweight but supple cashmere. This outfit representing January fashions would have been quite expensive.

Almanacs (or “annuaires” in French) were guides published annually. They typically contained useful charts and information about astrology, the weather, religious holidays, and so on. Specialized almanacs for women, known as “pocket books,” flourished by the mid-eighteenth century and functioned as precursors to the full-fledged fashion journal. The smaller, pocket-size format of fashion-centric almanacs encouraged practical use. For example, this particular almanac features extensive guides to navigating Paris’s shops and related fashion services, and could have been very helpful to have on hand while out shopping. The exceptional quality and detailed nature of this almanac’s twelve plates were calculated to stimulate a desire to consume not only the clothing illustrated but also the book itself. The book also promotes related ventures from publisher Pierre de la Mésangère (1761-1831), including the fashion journal Journal des Dames et des Modes and satirical prints parodying the same garments his fashion journals advocated. One of the promoted 1814 prints is also on view; another is featured in the exhibition’s final section. [CW]

The trendy young people known in Paris as “Incroyables” (Incredible Men) and “Merveilleuses” (Magnificent Women) were the subjects of a series of thirty-three conspicuously large standalone prints drawn by the artist Horace Vernet (1789-1863), who also made drawings for fashion plates during this early period in his career. The images have a casual quality that evokes a quickly drawn sketch. Though typical of fashion plates, this casual quality appears striking when presented at the large scale associated during this period with folio-sized publications treating more “serious” topics in the arts and sciences.

Given the awkward proportions of this woman’s columnar dress and puffed-up hat, one might wonder -- is this a fashion plate, or a fashion parody? The extreme nature of the sartorial choices suggests the latter, but the caption is austere and business-like (“Straw hat ornamented with crêpe. Dress made of perkale [a fine cotton] ornamented with muslin”). A paragraph describing this print appeared in the 1814 Annuaire des Modes de Paris (also part of this exhibit):

“. . . With the exception of her hat, which is covered with lemon-colored gauze, her entire outfit is white. One has never seen so much embroidery, so many flounces, so many cinches around the arms, so many puffs at the base of the dress, and on the umbrella, such long fringes. All of this nevertheless has grace, all appears simple and naturel, because there is nothing here that is not fashionable and perfectly executed. . . .”

This bit of “puff” (a period term for sneaky, editorial-style advertisements) suggests that despite its sartorial excesses, the image was nevertheless meant to be consumed as a serious documentation (and demonstration) of high fashion. [CW]

Expanding the Fashion Journal, 1809–1878