Illustrating & Appropriating World Costume

Books illustrating non-European dress proliferated alongside fashion journals and encyclopedic books on historic and regional costumes. However, the politics underlying depictions of world costume for a European audience were especially complex. Many parts of the world had been visited by only a small number of Europeans, and the people populating countries like India, Turkey, and China (collectively deemed “The Orient,” or “The East”) appeared foreign to European eyes in every sense of the word. As such, European publications often treated these countries as foils supporting Europe’s view of itself as comparatively modern and progressive. Such conclusions were marshalled in support of European nations’ efforts throughout the nineteenth century to control and colonize other parts of the world.

We have chosen to focus on China in this display in order to demonstrate the multiple ways that a single foreign country’s clothing could be represented in the European context. Before the First Opium War of 1839, cultural contact between China and Europe was limited to tightly controlled commercial exchanges via a single city, Guangzhou (called Canton by Europeans at the time). Chinese people and their clothing had first appeared in European publications as part of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century missionary and ethnographic documentation. Such depictions then acted as inspiration for the eighteenth-century decorative style known as “chinoiserie.” An unsuccessful British attempt to establish official diplomatic relations in 1793 reignited European fascination with Chinese culture. By mid-century, tensions around trade exploded into the armed conflicts known as the Opium Wars fought between China and the allied forces of Britain and France (1839-44; and 1856-60). The increasingly uneasy relationship between Europe and China during the early nineteenth century arguably affected how China was depicted by European designers and satirists, and how Europeans viewed China’s influence on their own culture, which included fashion. [CW]

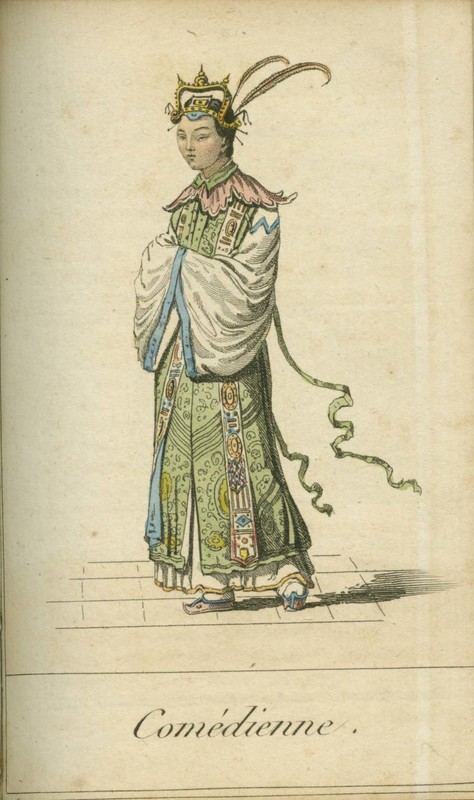

Most of the images in The Costume of China depict street vendors or representatives of various professions, but this woman “of distinction” (meaning a member of the nobility in Europe) would have appealed to Europeans’ notion of China as a source of luxury products like silks. A British soldier named George Mason (1770-1851) based this book on his 1790 visit to Guangzhou. “For the better information of his friends in Europe,” he writes in the introduction, “the Editor obtained correct drawings of the Chinese in their respective habits and occupations.” The Chinese origin of the drawings bolstered the book’s claims to authenticity.

The accompanying text, however, reveals European ambivalence towards both Chinese culture and European fashion. In the opening shown here, Mason highlights the modesty of Chinese women’s dress as a favorable contrast to European fashions, which had become scandalously revealing in the mid-1790s. He further claims that “The fashions of the Chinese never vary . . . and are perhaps emblematic of the stability of [the Chinese woman’s] affections.” By contrast, European culture portrayed European women’s affections as dangerously prone to in-stability. Satirists regularly drew on parallels between this emotional unpredictability and the frequent changes in fashion. But Mason also laments what he perceives to be upper-class Chinese women’s comparative lack of agency. He describes them, rather dramatically, as “many curious flowers, born equally to blush unseen, [who] are reared by their proprietors, come to maturity, fade, and die in their possession.” As a whole, this passage implies that the ingenuity of the European (male) gaze had successfully made this hidden creature knowable, in turn teaching European women to appreciate the liberal nature of their society while urging them not to abuse its freedoms. [CW]

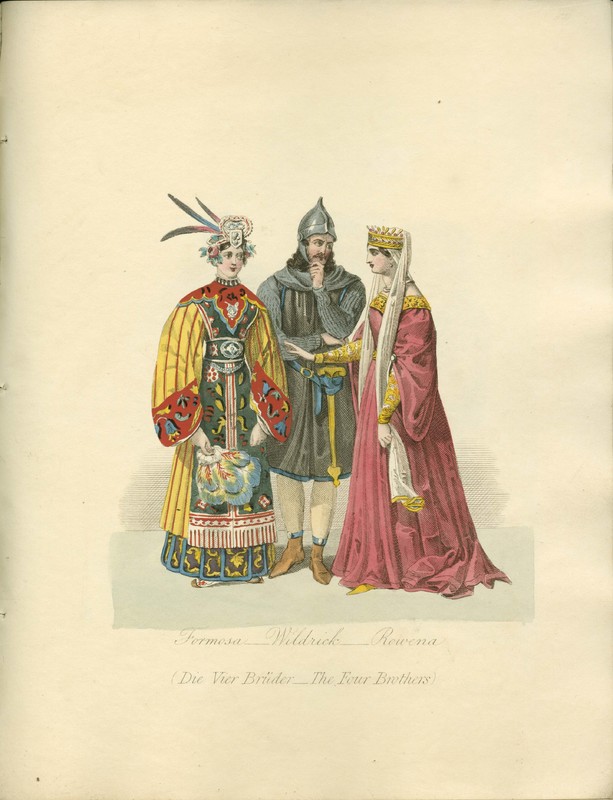

Publications were often made to record the costumes worn by attendees at “fancy,” or fantasy, balls. The three costumes shown here, which were worn at an 1828 ball in Vienna, were worn as part of a quadrille adapted from the German romantic author La Motte Fouque’s Die Vier Brüder (The Four Brothers). The original tale’s scenario allowed the masqueraders to dress as Romans, Druids, Anglo-Saxons, and Chinese. The costume for “Formosa,” the Chinese character, seems to have been adapted from an image of a Chinese actress in the pocket-size French guide to Chinese costume shown below. [CW]

Both images depict a woman in a “costume” intended for a performance. But they also communicate the idea that all Chinese dress was in essence costume rather than fashion -- that is, timeless and unchanging. In the image from the ball, the Chinese costume is able to coexist in a narrative alongside what would have been seen as clearly historical European costumes. The text accompanying the depiction of the Chinese actress reiterates European perceptions of Chinese dress as unchanging, stating that the period clothing depicted “does not differ very much from their current costume.” Further, this publication demonstrates the re-use of Chinese costume plates across long periods of time: the same image had appeared in an earlier French publication, which was based on the British series of 1800 that included the “Female Mandarin of Distinction.” Meanwhile, European fashions had shifted dramatically during the same twenty-one-year span. [CW]

This caricature in Observations sur les modes et les usages de Paris...(Observations of the fashions and customs of Paris...) of a fashionable European woman’s morning “toilette,” or dressing routine, simultaneously highlights and breaks down the divisions between “costume” and “fashion,” and between “Europe” and “other” shown throughout this exhibition. A woman stands before a mirror in her undergarments, attended by three crudely racialized Chinese men. The man on the right prepares to slip a dress over her head. While this dress’s upper portion resembles fashionable European shapes for sleeves and necklines, its lower half, a colonnade of tasseled fringes, mimics the over-garment worn by the middle Chinese man.

On the surface the image simply parodies a European fashion for dresses that claimed Chinese inspiration; a similar dress was pictured in a print from the fashion-focused Incroyables et Merveilleuses series, reproduced below. In “La Toilette Chinoise,” however, the men’s clothing reads distinctly as costume, rather than fashion. By rendering the Chinese men as grotesque caricatures, the print signals a creeping anxiety about the “costumes” of non-European people migrating from the closely circumscribed confines of images in European illustrated books, and the fantasy world of masquerades, into the everyday wardrobes of fashionable European women. [CW]

Depictions of Regional Costume in Illustrated Books

About the Exhibit