Essentially, the Index was a list of publications that the Catholic Church condemned, and prohibited, as heretical or immoral. The first Index, which contained 230 titles, was published by the University of Paris in 1544, followed by one from Louvain in 1546. While other similar lists were issued shortly afterwards, anxious booksellers managed to resist the pressure of the Church for some time. However, the Index eventually established itself as a universally accepted list through the endorsement of the Council of Trent (1545-1563), the most important ecumenical gathering designed to counter-attack the protestant reformation. Thus the Index published in 1564 became the foundation of all subsequent ones. In 1571, Pope Pius V instituted the Congregation of the Index, a bibliographical institution that updated and republished the content of the list. The last edition was published in 1948, and it was officially withdrawn in 1966.

Our holdings at Special Collections include editions of the Index dating from the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. In this post, I have included images from the earliest imprint we possess, Index librorum Prohibitorum: cum regulis confectis per patres a Tridentina synodo delectos (Antwerp: Christopher Plantin, 1570).

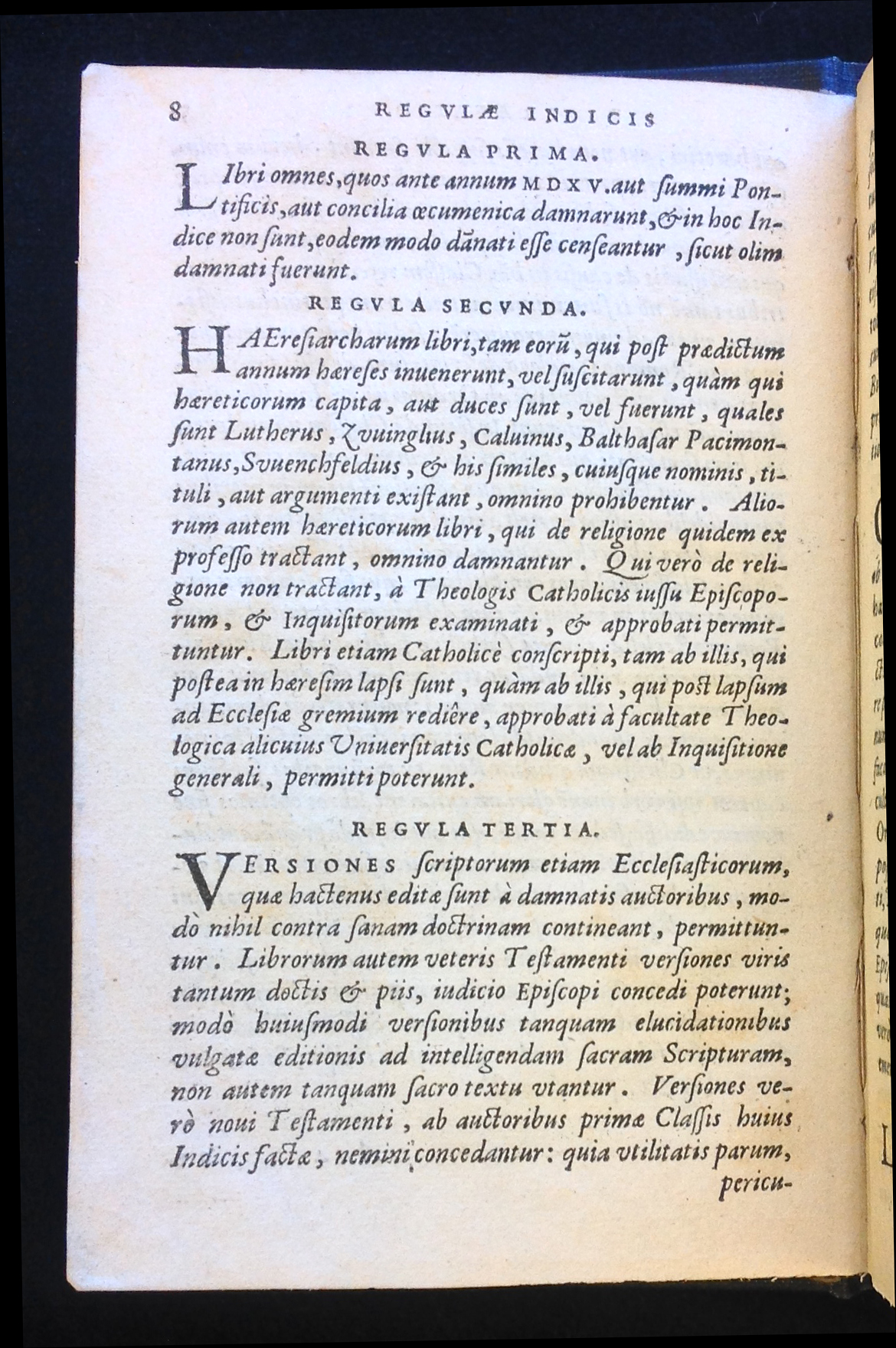

Index librorum prohibitorum: cum regulis confectis per patres a Tridentina synodo delectos (Antwerp: Christopher Plantin, 1570). Page 8.

The book opens with an explanation of the careful criteria or rules (regulae) that a group of theologians selected at the Council of Trent followed in order to make the list. For instance, it is rather comforting to learn that, according to rule 3 (regula tertia) versions of ecclesiastical writers that had been already edited by forbidden authors could be allowed as long as they did not contain anything against the right doctrine. Indeed, perhaps the key to understand this publication fully is that it did not contain just dangerous books but also dangerous authors. For instance, Copernicus’ De revolutionibus was still OK to read but Andreas Osiander, the author of the prologue, and Georgius Ioachinus Rheticus, Copernicus’ disciple, were declared personae non gratae in the Index.

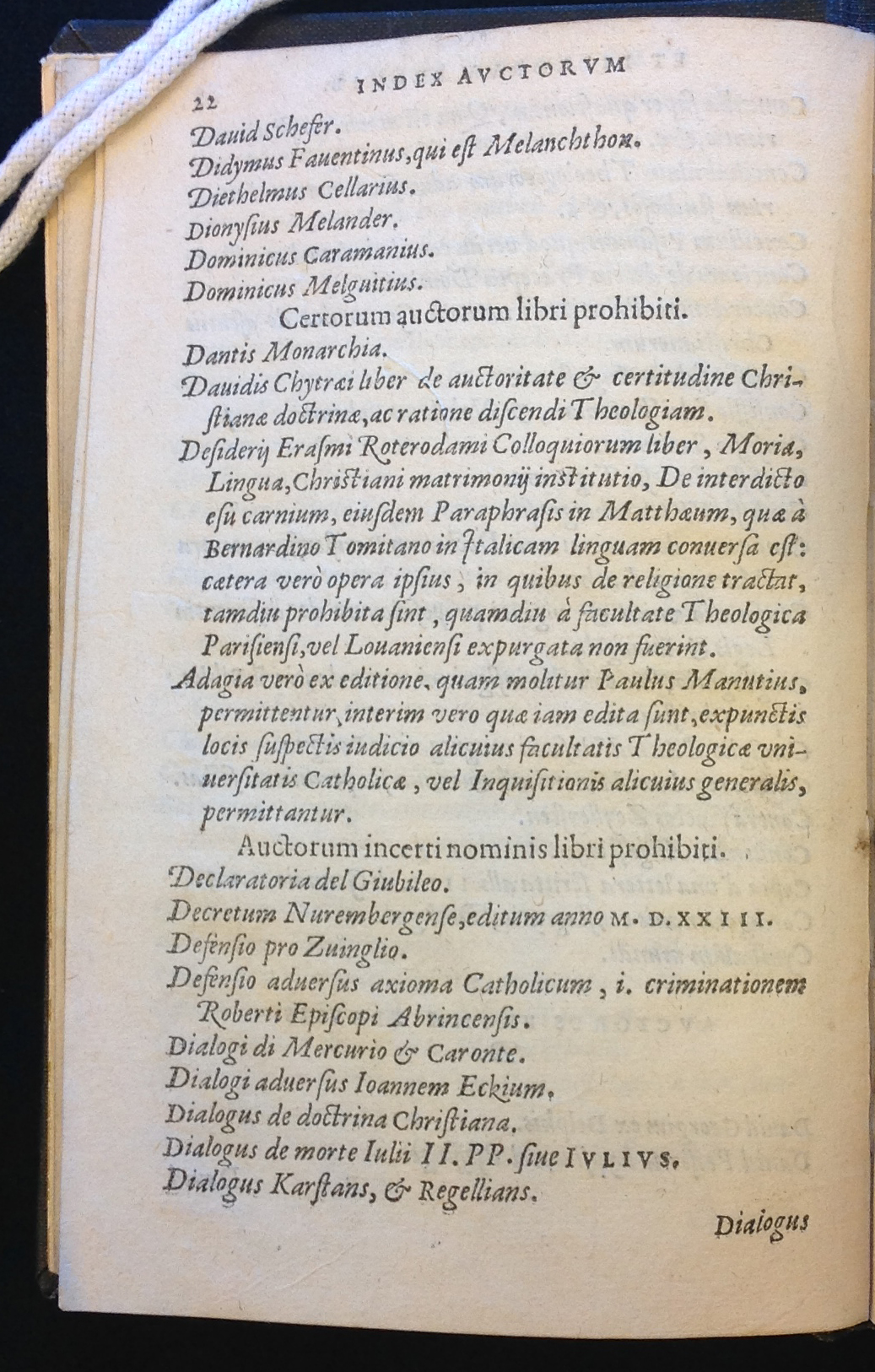

Index librorum prohibitorum: cum regulis confectis per patres a Tridentina synodo delectos (Antwerp: Christopher Plantin, 1570). Page 22.

We can be certain of one thing: these Inquisition folks really did their homework. In other words, any kind of work, of any genre one can imagine (philosophy, literature, theology, poetry, etc.) was carefully read. For instance, as seen on the page displayed above, the censors specifically tell us which works by Erasmus of Rotterdam were in fact dangerous. His book on Latin proverbs, Adagia, was forbidden with the exception of the edition that Paulus Manutius was then preparing. For the previous editions, the authors of the list strongly recommend that the polemical passages be removed following the judgment of a theologian from a Catholic university or of a member of the Inquisition.

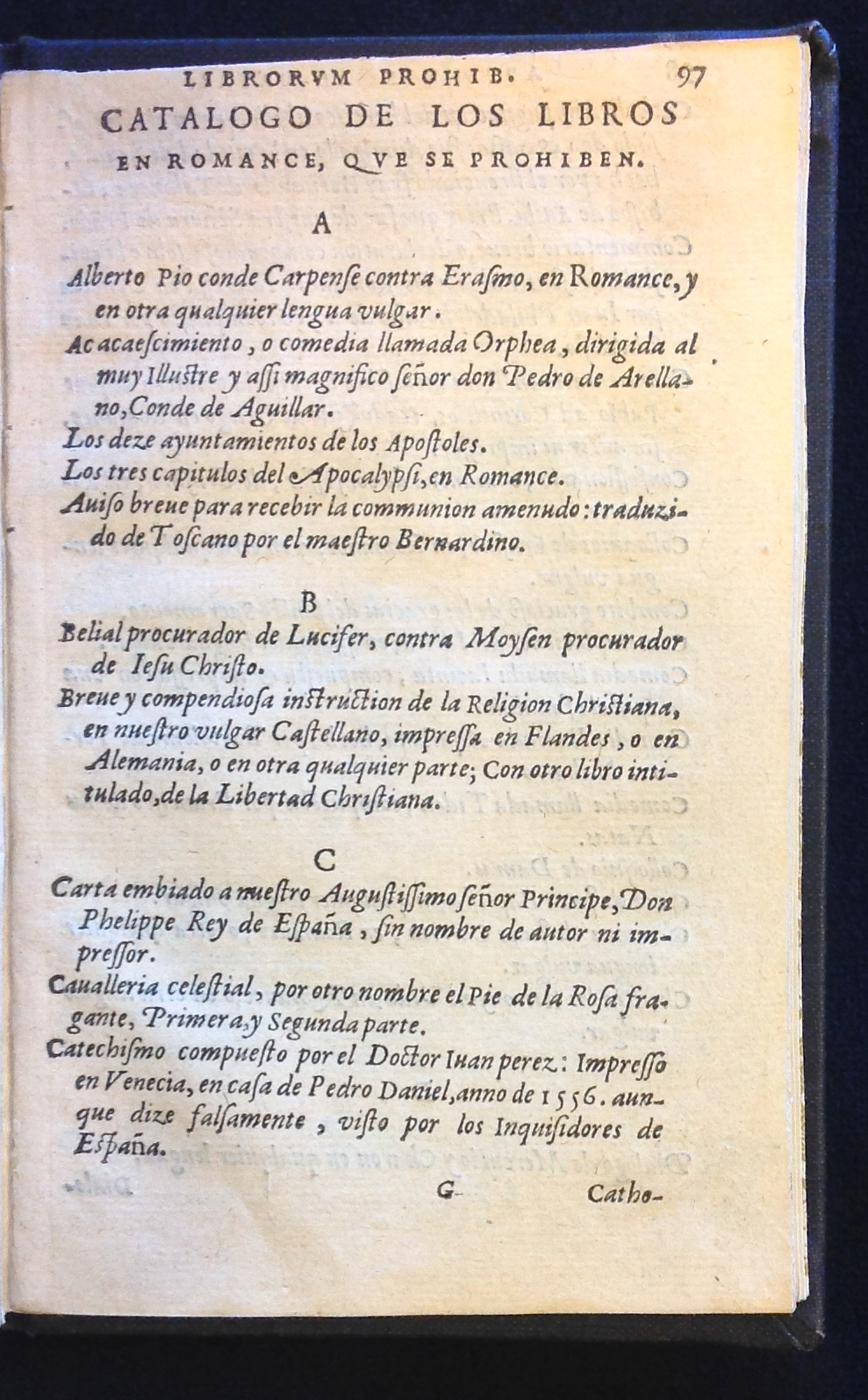

Index librorum prohibitorum: cum regulis confectis per patres a Tridentina synodo delectos (Antwerp: Christopher Plantin, 1570). Page 97.

This edition is mostly in Latin but it also adds a charming local flavor by including especial sections in French, Dutch, and Spanish. For example, we learn of the condemnation of a catechism by Doctor Juan Perez, published in Venice in 1556. The publisher of this catechism, Pedro Daniel, falsely claims that the books had been seen by the Spanish Inquisition (visto por los Inquisidores de España).