Our featured book is a copy of the second edition of the famous sixteenth-century blood-letting treatise for barber-surgeons, Discourses of Pietro Paolo Magni of Piacenza on how to bleed, attach leeches and cups, perform massages and blistering to the human body (Discorsi di Pietro Paolo Magni piacentino sopra il mondo di sanguinare, attaccar le sanguisugue, & le ventose far le fregagione & vessicatorij a corpi humani). It was published in Rome in 1586.

Historically, the practice of drawing blood from a patient, known as phlebotomy, was connected to the ancient theory of the four humors. According to this theory, the human body consisted of four vital fluids: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. To keep oneself healthy, one needed to keep a perfect balance between these fluids with the aid of a proper diet, medicines, and blood-letting.

The second edition of this manual is remarkable for introducing some important changes. The engraver Cherubino Alberti designed a new illustrated title-page, replacing the one that Adamo Scultori had created for the first edition of 1584. This new title-page announced that the text had been corrected and augmented by new recommendations by the author himself (corretti & ampliati de utili avvertimenti dal propio autore). The central text is flanked by a bearded physician on the left and a younger barber-surgeon on the right. The physician displays his professional credentials as a result of a university education by carrying a large book under one arm and holding a urine flask, which, for a sixteenth-century reader, symbolized the prestigious expertise of the professional physician. Across from him the barber-surgeon carries a portioned box as the attribute of his trade. Probably, this box is supposed to contain a selection of medicines, alluding to the activities of the twin doctor patrons of barbers’ guilds, saints Cosmas and Damian, who were sent to martyrdom after being caught while collecting herbs for medicines. Actually, the allusion to these two saints is obvious in the title-page of the first edition, where the figures of the physician and the barber-surgeon appear with haloes over their heads.

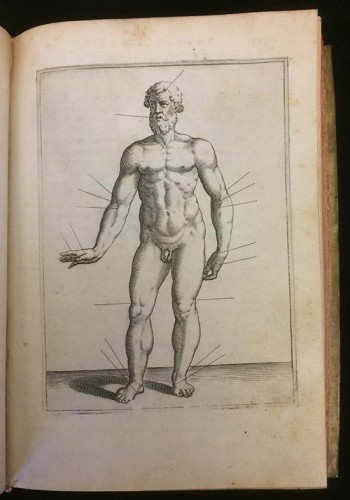

Adamo Scultori, Human Figure, Discorsi di Pietro Paolo Magni piacentino sopra il mondo di sanguinare attaccar le sanguisugue, & le ventose far le fregagione & vessicatorij a corpi humani (Roma: Bartolomeo Bonfadino, 1586)

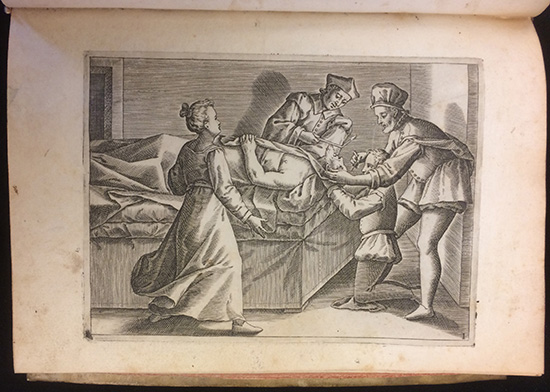

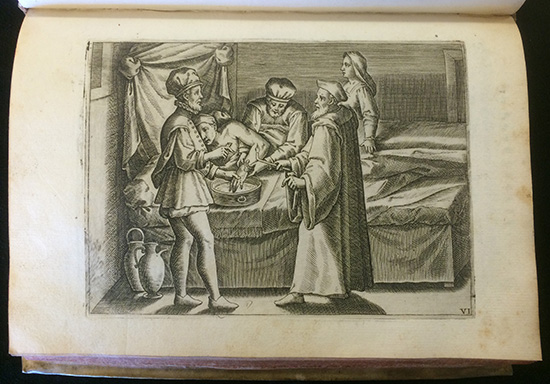

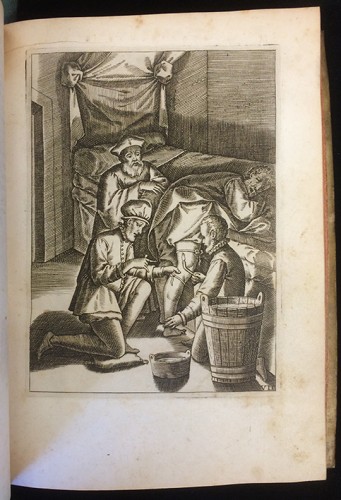

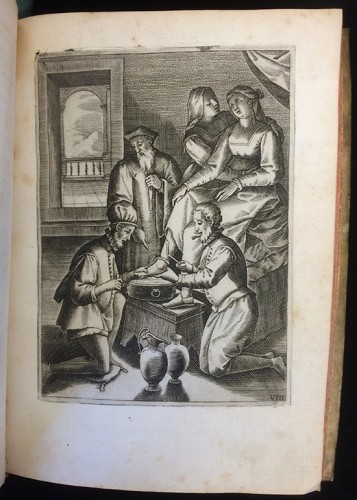

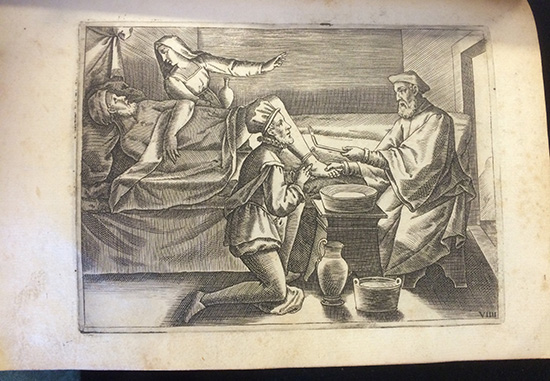

The treatise contains eleven full-page copperplate engravings whereby Magni makes recommendations not only about the precise body locations for blood-letting but also about the different postures for all the people involved in this operation: patient, physician, barber, assistant, and even relatives. In brief, the plates are an extraordinary historical document for depicting for the first time a medical practice in a real context. By the inclusion of strikingly realistic details, such as the architecture of a private room or the dramatic expression of patient and relatives, the engraver has successfully recreated the intimate atmosphere in which this sort of medical practices would have taken place.

Adamo Scultori, Plate I, Discorsi di Pietro Paolo Magni piacentino sopra il mondo di sanguinare attaccar le sanguisugue, & le ventose far le fregagione & vessicatorij a corpi humani (Roma: Bartolomeo Bonfadino, 1586)

Adamo Scultori, Plate VI, Discorsi di Pietro Paolo Magni piacentino sopra il mondo di sanguinare, attaccar le sanguisugue, & le ventose far le fregagione & vessicatorij a corpi humani (Roma: Bartolomeo Bonfadino, 1586)

Adamo Scultori, Plate VII, Discorsi di Pietro Paolo Magni piacentino sopra il mondo di sanguinare, attaccar le sanguisugue, & le ventose far le fregagione & vessicatorij a corpi humani (Roma: Bartolomeo Bonfadino, 1586)

Adamo Scultori, Plate VIII, Discorsi di Pietro Paolo Magni piacentino sopra il mondo di sanguinare, attaccar le sanguisugue, & le ventose far le fregagione & vessicatorij a corpi humani (Roma: Bartolomeo Bonfadino, 1586)

Adamo Scultori, Plate VIIII, Discorsi di Pietro Paolo Magni piacentino sopra il mondo di sanguinare, attaccar le sanguisugue, & le ventose far le fregagione & vessicatorij a corpi humani (Roma: Bartolomeo Bonfadino, 1586)

Traditionally, and particularly before the publication of Andreas Vesalius’ De humani corporis fabrica libri septem in 1543, doctors refused to deal with human flesh themselves. Instead, they focused on giving instructions, delegating tasks such a dissection and blood-letting to barber-surgeons. This distinction of roles is consistently illustrated through each of these extraordinary plates.

Our copy of Magni's manual is part of The Le Roy Crummer Collection.