This is a guest post authored by Caitlin Moriarty, a Reader Services Assistant in the Special Collections Library and 2nd year MSI student at the University of Michigan School of Information.

The Russian writer Sergei Dovlatov, one of the most beloved authors of the late Soviet period, was never published in the Soviet Union during his lifetime except under highly censored conditions - instead his work was published in Ann Arbor. In the 1970s and 80s, Ann Arbor was home to two prominent Russian-language emigre presses, Ardis and Hermitage Press, which published the writing of those who would not or could not be published in the USSR. The records of Ardis are held by the University of Michigan Special Collections Library, and include correspondence with Dovlatov and his wife, as well as manuscripts of articles and materials related to the publication of his books. In addition to Dovlatov, the collection contains materials about many other writers who worked with the Ardis such as Mikhail Bulgakov, Vladimir Nabokov, Tatyana Tolstaya, and Marina Tsvetaeva, including correspondence and manuscripts. Also included are business records, photographs, and artwork produced by the Ardis, and personal papers from Carl and Ellendea Proffer.

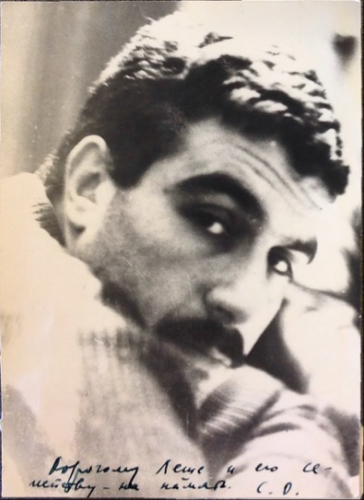

A photograph inscribed by Sergei Dovlatov. Box 19, Ardis Records,

University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Library)

Ardis was founded in Ann Arbor, Michigan in 1971 by Carl Proffer, a professor in the University of Michigan Slavic Department, and his wife Ellendea Proffer, a professor of Russian Literature at Wayne State University. Both had scholarly interests in modern Russian literature, which brought them to Moscow in 1969 while Carl was on a Fulbright scholarship. This year in the USSR allowed them to make connections in Russian literary circles and to gather unpublished work of contemporary authors with the hope of making it available both in the USSR and abroad. The manuscripts that they collected on this trip became the first works published under the subsequently founded Ardis.

The fact that his work was not published in the Soviet Union does not mean that Dovlatov was not read there. Copies of Dovlatov’s stories were privately circulated in the Soviet Union as samizdat, copies reproduced manually from other copies, or as tamizdat, copies published abroad that were snuck back into the country. Ardis would regularly send one third of its press runs to libraries in the USSR, which were generally either confiscated by the K.G.B. or end up on the black market (1). Dovlatov’s first collection of stories, The Invisible Book (Невидимая книга), was published by Ardis in 1977, and it is likely that some of the books may have made their way to the Soviet Union.

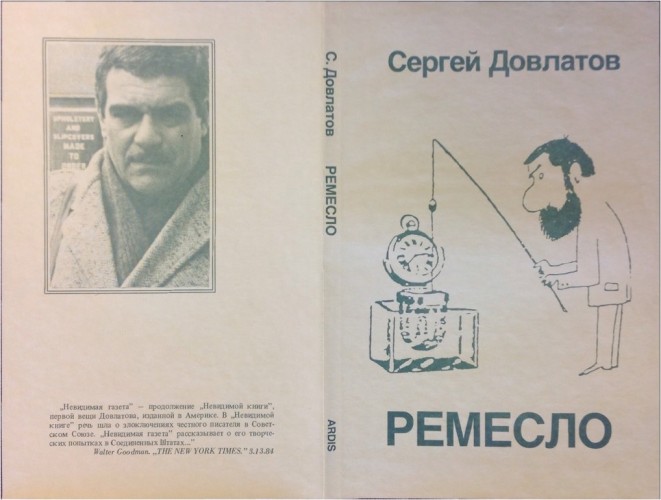

A proof of the cover for Ремесло: Повесть в двух частях (Craft: A Story in Two Parts), published by Ardis, 1985. Box 3, Ardis Records, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Library)

In most of Dovlatov’s stories, the narrators are thinly veiled versions of himself, friends, or members of his own family, and could easily be anecdotes from his own experiences. The tradition the anecdote genre (анекдоты) in Soviet Russia was more than just telling a joke. Anecdotes often had political or social themes, and the humor of the punchline came from the irony that it was not a joke at all, but that Soviet life was truly and inherently absurd (2). Dovlatov’s stories have this quality, ringing true to the point where it is hard to tell where the line of fiction blurs and the story begins. In an article in The New Yorker, James Wood describes Dovlatov’s method, writing that “he collects vignettes, loud portraits, bitter jokes, comic tales, absurd episodes, black anecdotes, and then delights in bringing them out of the ether of hearsay or memory and giving them new life in print,” (3).

In 1979, Dovlatov left the Soviet Union and settled in Forest Hills, Queens, part of the third wave of Russian emigres that included many of the writers in his own social circle. The most prominent member of this wave was the poet Joseph Brodsky, whom Dovlatov had known since university. With the assistance of the Proffers, Brodsky became poet-in-residence at the University of Michigan after being strongly encouraged to leave the Soviet Union.

Sergei Dovlatov, center, with Joseph Brodsky to his left, Sasha Sokolov to his right, and Professor Carl

Proffer, far right, at a panel discussion to recognize the career of Carl Proffer, March 1984. Photograph from sergeidovlatov.com. (http://sergeidovlatov.com/img/ann-arbor-2.jpg)

Of Dovlatov, Brodsky said he was “the only Russian writer whose works will be read all the way through”. Dovlatov was equally enamored of Brodsky, writing in The Invisible Book that “He pushed Hemingway out of the background and became my literary idol forever.” In March, 1984, Dovlatov came to the University of Michigan at the invitation of Brodsky to participate in a panel of Russian emigre writers and artists that was put together in honor of their mutual friend, Carl Proffer. Proffer would lose his battle with cancer a few months later, and Dovlatov himself would pass away in 1990 at just 49, but his friendship with Brodsky and Ardis would forever connect him to the University of Michigan.

Notes/References

(1) Ardis Records, Biography, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Library) http://quod.lib.umich.edu/s/sclead/umich-scl-ardis?byte=359774;focusrgn=bioghist;subview=standard;view=reslist

(2) Seth Graham, “A Cultural Analysis of the Russo-Soviet Anekdot” (Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pittsburgh, 2004).

(3) James Wood, “Sergei Dovlatov and the Hearsay of Memory”, The New Yorker, April 7, 2014. http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/sergei-dovlatov-and-the-hearsay-of-memory