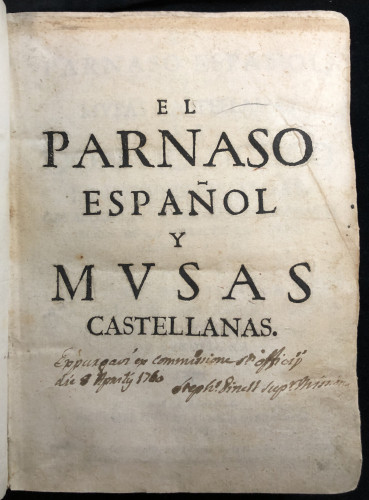

When examining a selection of rare books that had been requested for a class presentation about the impact of censorship in early modern Spain, I noticed something truly remarkable in one of these books. Our copy of the eighteenth-century edition of Francisco de Quevedo y Villegas’ El Parnaso español y musas castellanas, published in Barcelona in 1703, had been manually, and massively, expurgated by a representative of the Spanish Inquisition, Joseph Pinell, as he himself wrote on the title page: Expurgavi ex Commisione S(anc)ti Officii die 8 Aprilii/ Joseph Pinell, Supr(emus). Missionum (I, Joseph Pinell, the highest of delegates, have expurgated it by a mandate of the Holy Inquisition on April 8 1760).

Title page of Francisco de Quevedo y Villegas. El Parnaso español y musas castellanas (Barcelona: Rafael Figueró, 1703)

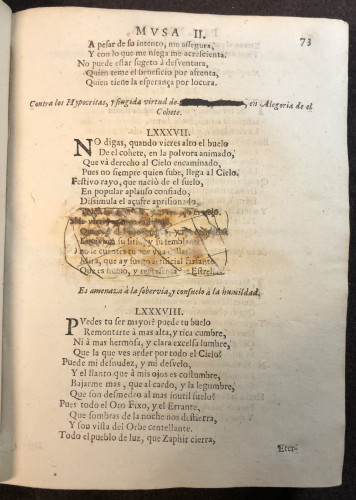

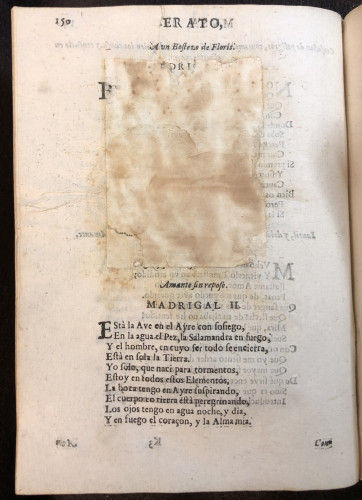

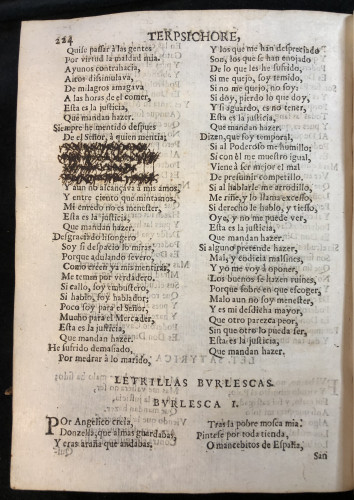

As we discussed in a previous post, in the sixteenth century the Catholic Church strongly reacted against the ideological influence of the Protestant creed by publishing a series of Indices librorum prohibitorum, or indexes of forbidden books, which contained titles and authors considered theologically dangerous to the teachings of the Church of Rome. The first Index, which included 230 titles, was published by the University of Paris in 1544, being followed by others in 1546, 1549, and 1559. However, the first Index intended to be universally applicable throughout Christendom, since the Council of Trent inspired it, was published in 1564, becoming the model for future Indices. In Spain, the censorship of books turned into a perversely sophisticated activity. Thus, extremely comprehensive Indices were published by well-known intellectual and ecclesiastical figures, listing not only the forbidden authors and works, but also, with painstaking precision, the passages within a particular book that should be emended or expurgated. Essentially, the expurgation in our copy of El parnaso español consisted of obliterating numerous passages of various length, like a few words or verses, by erasures made by pen, and, more dramatically, of cancelling entire poems by gluing pieces of paper over them.

Expurgation on page 73, from Francisco de Quevedo y Villegas. El parnaso español y musas castellanas (Barcelona: Rafael Figueró, 1703)

Expurgation on page 150, from Francisco de Quevedo y Villegas. El parnaso español y musas castellanas (Barcelona: Rafael Figueró, 1703)

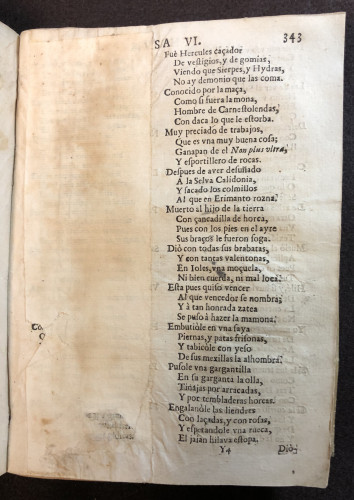

Expurgation on page 224, from Francisco de Quevedo y Villegas. El parnaso español y musas castellanas (Barcelona: Rafael Figueró, 1703)

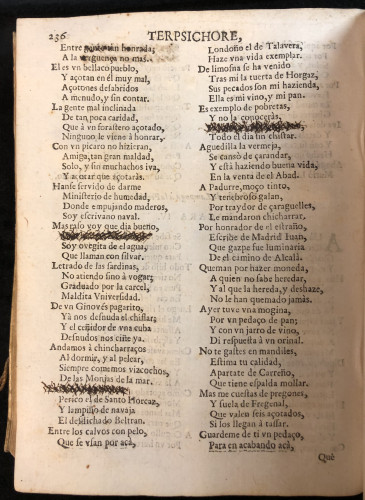

Expurgation on page 236, from Francisco de Quevedo y Villegas. El parnaso español y musas castellanas (Barcelona: Rafael Figueró, 1703)

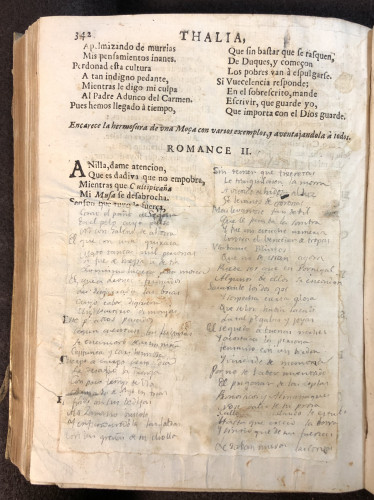

Expurgation on page 342, with the verses of the poem added by hand by a reader, from Francisco de Quevedo y Villegas. El parnaso español y musas castellanas (Barcelona: Rafael Figueró, 1703)

Expurgation on page 73, from Francisco de Quevedo y Villegas. El parnaso español y musas castellanas (Barcelona: Rafael Figueró, 1703)

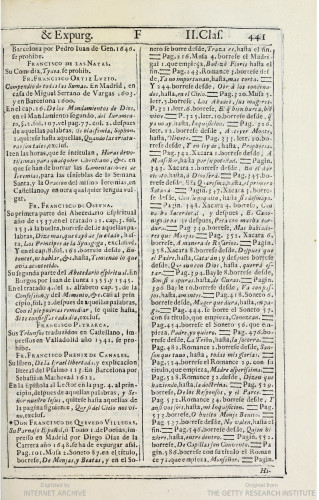

Fernando Plata Parga has thoroughly explained how our copy of El parnaso español faithfully reflects the expurgatory recommendations that were first included in the Novissimus librorum prohibitorum, et expurgandorum index pro Catholicis Hispaniarum regnis Philippi V. Reg. Cath. (Madrid: Ex typographia musicae, 1707), a voluminous work of learned censorship initiated by Diego Sarmiento y Valladares and completed by Vital Marín. Overall, as Plata Parga argues, these expurgations closely follow one of the recommendations listed in the Novissimus index, to be precise, Regla 16, which encouraged the suppression of religious allusions and quotations from the Bible in a context that could be interpreted as irreverent to the dignity of the religious orders, the Church, and the State.1

Page with detailed instructions to expurgate El parnaso español, from Diego Sarmiento y Valladares & Vital Marín. Novissimus librorum prohibitorum, et expurgandorum index pro Catholicis Hispaniarum regnis Philippi V. Reg. Cath. (Madrid: Ex typographia musicae, 1707). Courtesy of the Getty Research Institute

Nevertheless, anyone carefully reading the poems of El Parnaso español would soon realize that Quevedo did not challenge any doctrines of the Church but, as an exceptionally playful and erudite poet, he borrowed the ecclesiastical and ritualistic idiom of Christianity for the sake of his satirical poetry.

1. Fernando Plata Parga. "Inquisición y censura en el siglo XVIII : "El Parnaso español" de Quevedo. " La Perinola: revista de investigación quevediana 1 (1997): 173-188.