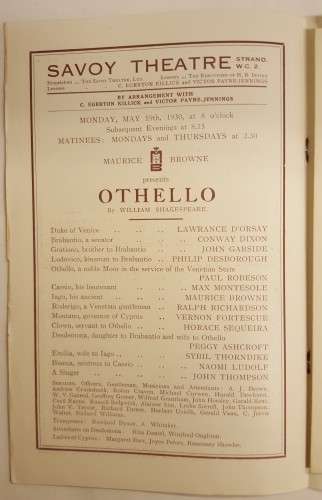

The exhibit Shakespeare on Page and Stage: A Celebration (Audubon Room, January 11-April 27, 2016) showcases both the textual and performance history of Shakespeare’s plays. With this post, we focus in greater detail on Paul Robeson’s performance as Othello in Ellen Van Volkenburg and Maurice Browne’s 1930 London production at the Savoy Theater.

In Othello, a Moorish general in the Venetian army secretly marries the daughter of a Venetian senator. Their marriage is quickly poisoned by Othello’s ensign Iago, who persuades Othello that Desdemona has been unfaithful to him. In agony over her supposed betrayal, Othello murders Desdemona before discovering her innocence and ultimately kiling himself. As a character, Othello embodies the tragic hero and since at least the 18th century has habitually been played as a tall, handsome man of great natural nobility and virtue, who falls only because the intensity of his passion for Desdemona makes him vulnerable to Iago’s deceit.

Othello is the only Shakespearean tragedy with a lead who is explicitly a person of color. For most of its performance history, the role was played by white actors in dark make-up. African American Ira Aldridge portrayed Othello to great acclaim in the mid-nineteenth century, but no other black actor played Othello on the London Stage until Paul Robeson took the part in Maurice Browne and Ellen Van Volkenburg’s 1930 production at the Savoy Theater.

Othello First Night Program, 1930. Ellen Van Volkenburg and Maurice Browne Papers, 1772-1983.

As the home of a large archival collection of Ellen Van Volkenburg and Maurice Browne materials, the Special Collections Library offers an intimate look at the staging of this historic production through newspaper clippings, photographs, stage and costume designs, programs, and even the very breastplate worn on stage by Paul Robeson.

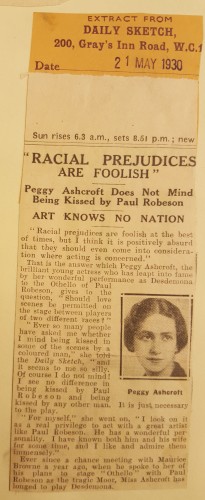

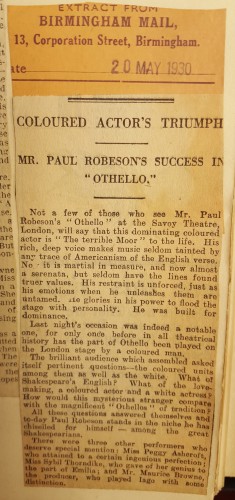

Although England, unlike America at that time, was not formally segregated, it was by no means free from racism. The previous year, in fact, Robeson and his wife had been denied entry to the Savoy restaurant. Articles written both before and after opening night often included discussions of race - both Othello's and Robeson's. Peggy Ashcroft (Desdemona) addressed one strand of these conversations in the article reproduced below, in which she notes, "Ever so many people have asked me whether I mind being kissed in some of the scenes by a coloured man...and it seems to me so silly. Of course I do not mind! I see no difference in being kissed by Paul Robeson and being kissed by any other man. It is just necessary to the play"

Newspaper clipping, 1930. Scrapbook 71. Ellen Van Volkenburg and Maurice Browne Papers, 1772-1983.

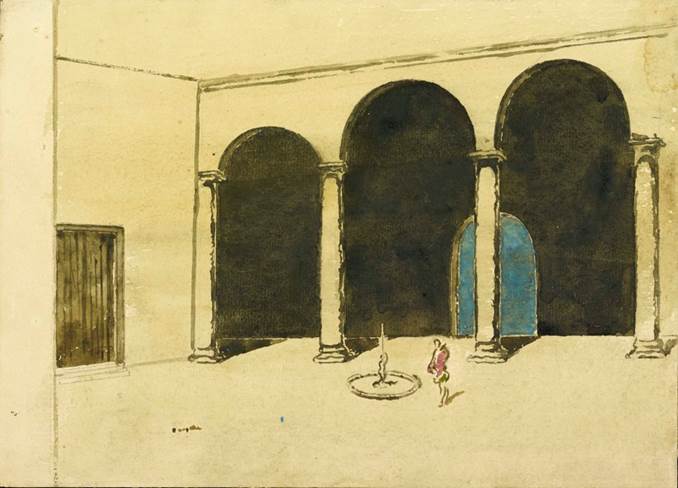

Several newspaper articles leading up to opening night looked forward with excitement to the participation of English painter James Pryde. Making his first forray into the theatrical world, Pryde agreed to design the sets for Browne's production, but ultimately his aesthetic skill as a painter did not fully translate to the stage. Reviews of the production critiqued the sets as unnecessarily ponderous and bulky. The watercolor designs below show the elegant beauty of the sets, but also reinforce the criticism that they overwhelemed and detracted attention from the comparatively dimminutive figures of the actors.

Stage design for Othello in pencil and watercolor by James Pryde, ca. 1930. Ellen Van Volkenburg and Maurice Browne Papers, 1772-1983.

Stage design for Othello in pencil and watercolor by James Pryde, ca. 1930. Ellen Van Volkenburg and Maurice Browne Papers, 1772-1983.

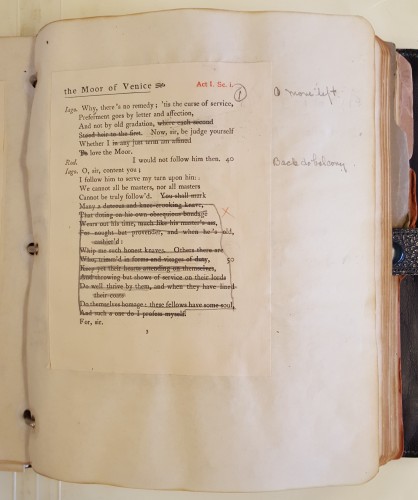

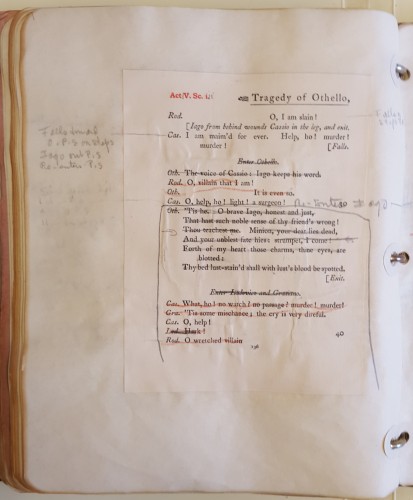

Another widespread criticism of the production centered on the extensive cuts made by Browne and Van Volkenburg, suggesting that these damaged the poetry and flow of the performance. Some of the cut passages can be seen below in Van Volkenburg's promptbook

Othello Promptbook, Act I, Scene i, ca. 1930. Ellen Van Volkenburg and Maurice Browne Papers, 1772-1983.

Othello Promptbook, Act V, Scene i, ca. 1930. Ellen Van Volkenburg and Maurice Browne Papers, 1772-1983.

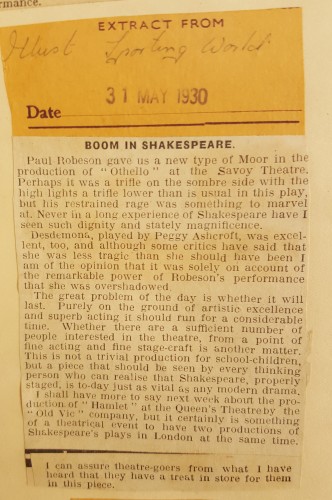

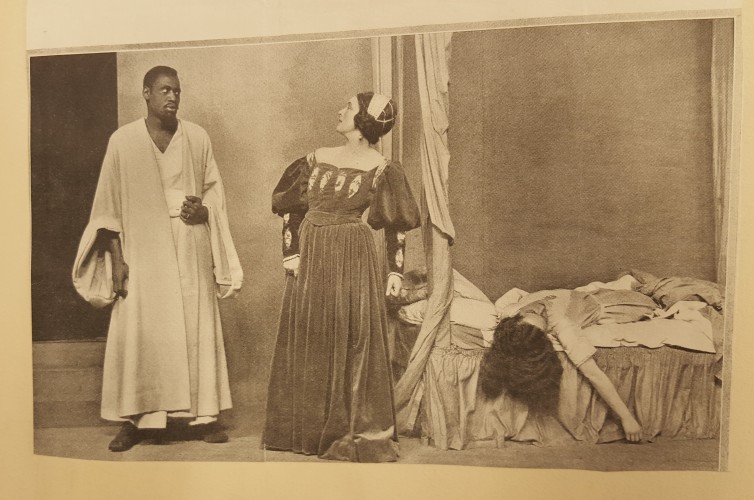

Despite these critiques, Robeson’s performance, was widely recognized as powerful and historic by both audiences and critics, attracting more than 20,000 attendees in its first few weeks. In describing Robeson's Othello, one of the reviewers (article reproduced below) affirmed,"to-day Paul Robeson stands in the niche he has chiselled for himself -- among the great Shakespeareans," and another went so far as to say, "Never in a long experience of Shakespeare have I seen such dignity and stately magnificence."

Newspaper clipping from scrapbook, 1930. Scrapbook 71. Ellen Van Volkenburg and Maurice Browne Papers, 1772-1983.

Newspaper clipping from scrapbook, 1930. Scrapbook 71. Ellen Van Volkenburg and Maurice Browne Papers, 1772-1983.

A graduate of Columbia law school, Paul Robeson had been frustrated by the many doors in the legal field that were closed to him because of his race. As he became increasingly involved with the Harlem art scene in the 1920s, he began taking on stage roles and performing African American spirituals. At the time of his debut as Othello, Robeson was already internationally known for his concerts and “the marvelous music of his voice” was praised as a key aspect of his performance. Robeson went on to play Othello in several later productions, including the first Othello with a black lead on Broadway in the 1940s. When that production went on tour, he took the unprecedented step of insisting that he would not perform to segregated audiences. Robeson saw acting in general, and his performance as Othello in particular, as an integral parrt of the social and policital activism that increasingly became his life’s work.

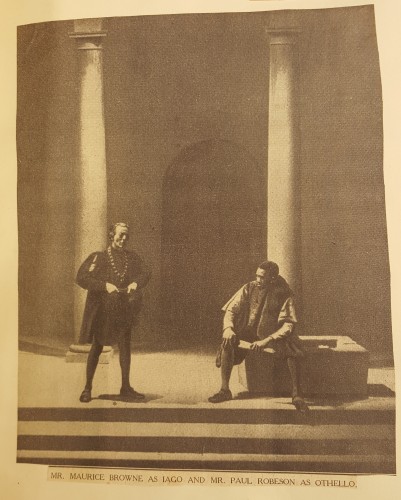

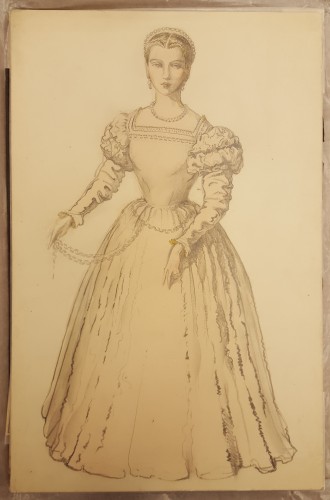

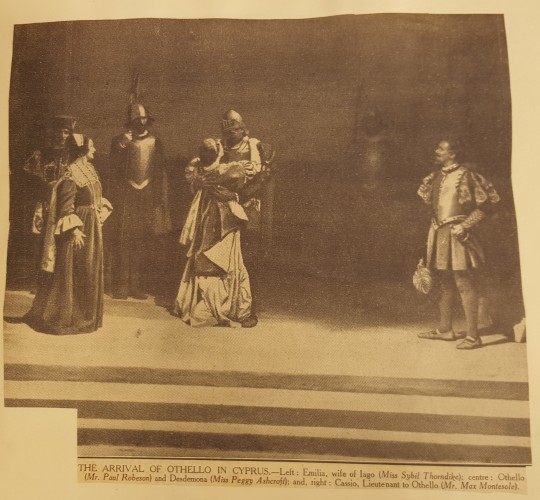

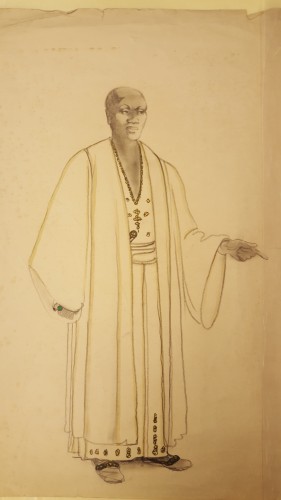

In closing, we offer a glimpse at an area of particular richness in the Van Volkenburg and Browne collection. Juxtaposing the costume designs of George Sherringham with photographs of the actors (and in the case of the breastplate, the costume itself) offers a unique view at the proceess of transformation as ideas move from page to stage.

Costume design for Othello by George Sherringham. Ellen Van Volkenburg and Maurice Browne Papers, 1772-1983.

Newspaper clipping photograph Scrapbook 71. Ellen Van Volkenburg and Maurice Browne Papers, 1772-1983.

Left: Costume design for Othello by George Sherringham. Right: Photograph of breastplate worn by Charles Robeson. Ellen Van Volkenburg and Maurice Browne Papers, 1772-1983.

Costume design for Desdemona by George Sherringham. Ellen Van Volkenburg and Maurice Browne Papers, 1772-1983.

Costume design for Emilia by George Sherringham. Ellen Van Volkenburg and Maurice Browne Papers, 1772-1983.

Newspaper clipping photograph Scrapbook 71. Ellen Van Volkenburg and Maurice Browne Papers, 1772-1983.

Costume design for Othello by George Sherringham. Ellen Van Volkenburg and Maurice Browne Papers, 1772-1983.

Newspaper clipping photograph Scrapbook 71. Ellen Van Volkenburg and Maurice Browne Papers, 1772-1983.